The moment, when it comes, has the inevitability of comic genius. Young Frederick Frankenstein, grandson of the count who started it all, returns by rail to his ancestral home. As the train pulls into the station, he spots a kid on the platform, lowers the window and asks, “Pardon me, boy; is this the Transylvania Station”?

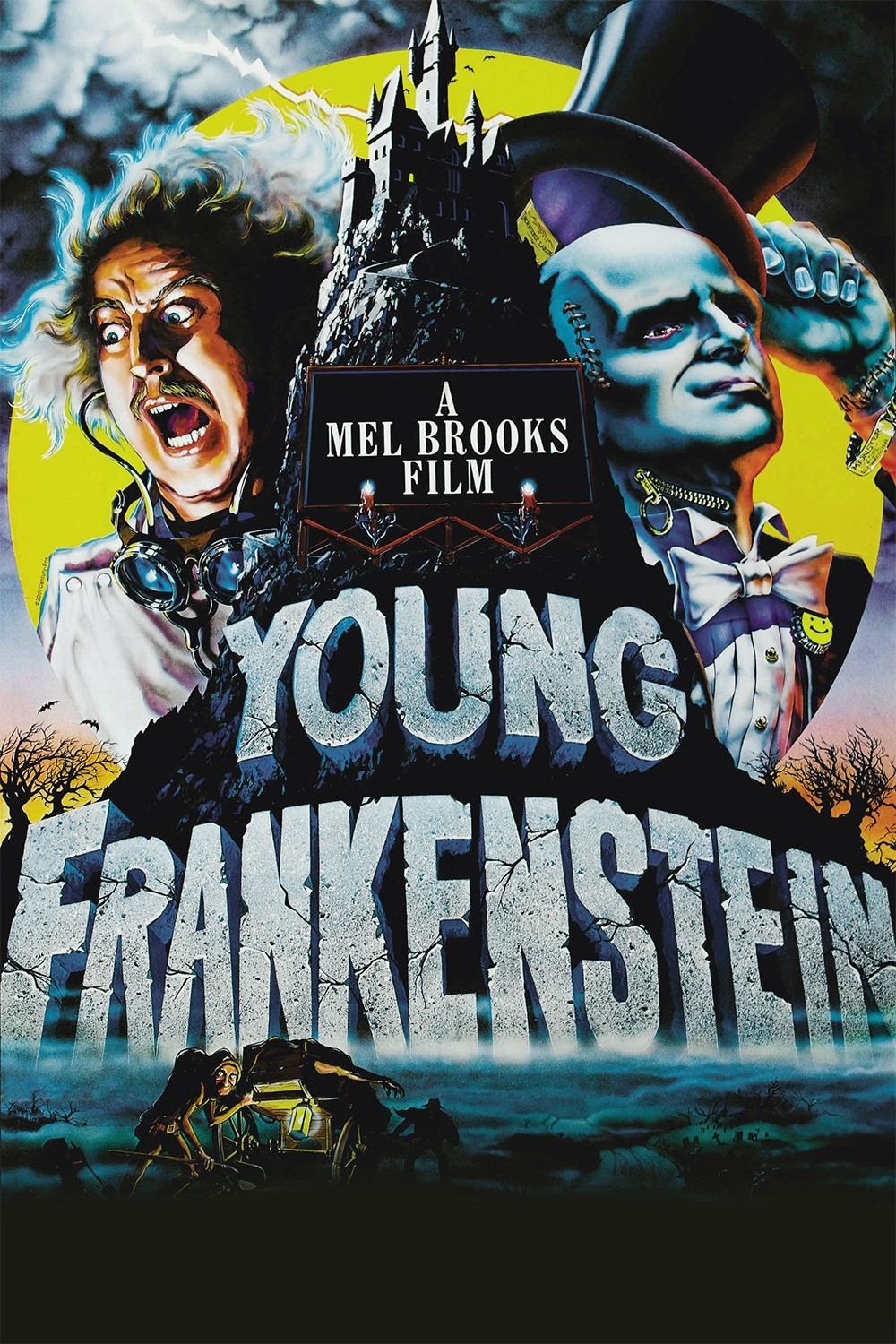

It is, and Mel Brooks is home with “Young Frankenstein,” his most disciplined and visually inventive film (it also happens to be very funny). Frederick is a professor in a New York medical school, trying to live down the family name and giving hilarious demonstrations of the difference between voluntary and involuntary reflexes. He stabs himself in the process, dismisses the class and is visited by an ancient family retainer with his grandfather’s will.

Frankenstein quickly returns to Transylvania and the old ancestral castle, where he is awaited by the faithful houseboy Igor, the voluptuous lab assistant Inga, and the mysterious housekeeper Frau Blucher, whose very name causes horses to rear in fright. The young man had always rejected his grandfather’s medical experiments as impossible, but he changes his mind after he discovers a book entitled How I Did It by Frederick Frankenstein. Now all that’s involved is a little grave-robbing and a trip to the handy local Brain Depository, and the Frankenstein family is back in business.

In his two best comedies, before this, “The Producers” and “Blazing Saddles,” Brooks revealed a rare comic anarchy. His movies weren’t just funny, they were aggressive and subversive, making us laugh even when we really should have been offended. (Explaining this process, Brooks once loftily declared, “My movies rise below vulgarity.”) “Young Frankenstein” is as funny as we expect a Mel Brooks comedy to be, but it’s more than that: It shows artistic growth and a more sure-handed control of the material by a director who once seemed willing to do literally anything for a laugh. It’s more confident and less breathless.

That’s partly because the very genre he’s satirizing gives him a strong narrative he can play against. Brooks’s targets are James Whale’s “Frankenstein” (1931) and “Bride of Frankenstein” (1935), the first the most influential and the second probably the best of the 1930s Hollywood horror movies. Brooks uses carefully controlled black-and-white photography that catches the feel of the earlier films. He uses old-fashioned visual devices and obvious special effects (the train ride is a study in manufactured studio scenes). He adjusts the music to the right degree of squeakiness. And he even rented the original “Frankenstein” laboratory, with its zaps of electricity, high-voltage special effects, and elevator platform to intercept lightning bolts.

So the movie is a send-up of a style and not just of the material (as Paul Morrissey’s dreadful “Andy Warhol’s Frankenstein”). It looks right, which makes it funnier. And then, paradoxically, it works on a couple of levels: first as comedy, and then as a weirdly touching story in its own right. A lot of the credit for that goes to the performances of Gene Wilder, as young Frankenstein, and Peter Boyle as the monster. They act broadly when it’s required, but they also contribute tremendous subtlety and control. Boyle somehow manages to be hilarious and pathetic at the same time.

There are set pieces in the movie that deserve comparison with the most famous scenes in “The Producers.” Demonstrating that he has civilized his monster, for example, Frankenstein and the creature do a soft-shoe number in black tie and tails. Wandering in the woods, the monster comes across a poor, blind monk (Gene Hackman, very good) who offers hospitality and winds up scalding, burning, and frightening the poor creature half to death.

There are also the obligatory town meetings, lynch mobs, police investigations, laboratory experiments, love scenes, and a cheerfully ribald preoccupation with a key area of the monster’s stitched-together anatomy. From its opening title (which manages to satirize “Frankenstein” and “Citizen Kane” at the same time) to its closing, uh, refrain, “Young Frankenstein” is not only a Mel Brooks movie but also a loving commentary on our love-hate affairs with monsters. This time, the monster even gets to have a little love-hate affair of his own.