Michael Moore’s surprising and extraordinarily winning “Where to Invade Next” will almost surely cast his detractors at Fox News and similar sinkholes into consternation. They get lots of mileage out of painting Moore as a far-left provocateur who’s all about “running America down.” But his new film is all about building America up, in some amazingly novel and thought-provoking ways. In my view, it’s one of the most genuinely, and valuably, patriotic films any American has ever made.

It comes billed not as a documentary but a comedy, and the first joke is its hilariously misleading title. You think it anticipates a stern, leftist denunciation of American foreign policy. Instead, Moore tells us the Joint Chiefs of Staff invited him to Washington, DC, to confess that all their wars since “the big one” have been disastrous and ask his advice. He responds by offering himself up as a one-man army who will “invade countries populated by Caucasians whose names I can mostly pronounce, take the things we need from them, and bring them back home to the United States of America.”

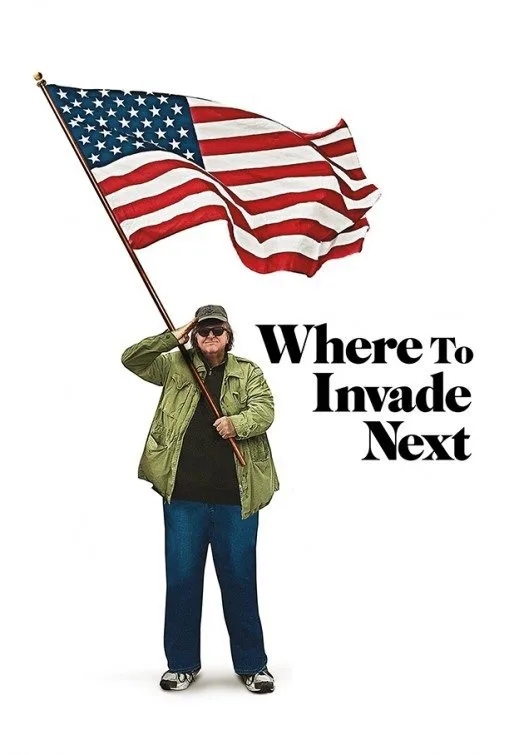

So, wearing his trademark baseball cap and literally wrapped in the flag, he sets off across the Atlantic searching out peoples to conquer who have things America needs. Yes, he knows all of these countries have their own share of problems. But he’s come, he says, “to pick the flowers, not the weeds.” And what a bouquet he assembles.

First stop is Italy, where he wonders why “Italians always look like they just had sex.” He finds some reasons for that happy glow in talking to a 30ish couple—he’s a cop, she works for a clothing company—who start enumerating all the paid vacation time they get. The basic portion, decreed by law, is four weeks, but when you add in government holidays and such, it comes closer to eight. They use all this time to vacation in places like Miami and Zanzibar, so there’s more than just sex (though we guess there’s plenty of that too) to explain their radiant tans and satisfied smiles.

After hearing about these citizens’ five months paid maternity leave, Moore invades two Italian companies—one makes the famous Ducati motorcycles—where he expresses mock-disbelief that such largesse could be good for business. But the CEOs of both firms genially argue that it is. Workers getting such benefits—and being allowed two-hour lunches where they can have home-cooked meals—makes for a healthier, happier and more productive work force, they say. A union representative notes that these gains have been hard-won and still require struggle. But the picture of an industrial situation where all sides seem to define success as cooperation, health and la dolce vita leads Moore to plant the Stars and Stripes on one factory floor, claiming the idea for the U.S.A.

Before considering the other countries he visits, it’s worth noting that all of this works so well not only because of the ideas presented but also because Moore is such a masterful comic storyteller and skilled polemicist. The film has a very definite point of view, of course; that’s what sets it apart from the bland pseudo-objectivity of our corporate news media. But Moore is clever enough to avoid preaching to the choir by also voicing the doubts and skepticism that Americans of other political persuasions would have.

After Italy, several episodes focus on different aspects of education. In France, he visits a provincial elementary school where the students’ hour-long lunches look like they come from a top Parisian restaurant; this is not only cheaper than the crap American kids are fed, the chef tells him, it’s also educational since it teaches about food and healthy eating. In Finland, one of the film’s most startling segments, Moore learns that until a couple of decades ago, student performance was about as lame America’s still is. Then the Finns decided to revolutionize their educational system. The reforms included eliminating homework and standardized testing and giving students more autonomy and free time. The result: Finland is now number one in educational rankings.

In Slovenia, Moore inspects a system where a college education is essentially free, even for Americans who have begun to flock there, unable to afford the exorbitant costs at home. In Germany, the filmmaker’s look at health care and benefits for middle-class citizens elides into the part of the film that’s most likely to draw the ire of American right-wingers, since it concerns how not just education but public policy in general decrees remembering and understanding the Holocaust. Moore says he comes from “a great country that was born in genocide and built on the backs of slaves,” and wonders whether such recognition of historical sins might actually benefit the U.S. too.

Two other countries prompt questions of crime and punishment. In Norway, Moore investigates a prison system where rehabilitation rather than punishment is the goal, even maximum security lock-ups are tailored to that end, and the maximum sentence is 23 years (the country now has one of the world’s lowest murder rates). In Portugal, he hears that eliminating all penalties for drug use and treating it as a health-care issue instead has resulted in decreased use. He also listens as three Portuguese cops talk movingly about how concern for “human dignity” is the most important part of their training.

Two underlying themes of the film, people power and women’s empowerment, converge in the film’s final two segments. In Tunisia (the only non-European and only Muslim country visited), he hears how, after the country’s 2011 revolution, the new Islamist government tried to keep a guarantee of equal rights for women out of the constitution, but bowed to include it after a massive popular uprising. And in Iceland, Moore learns that the only financial company that escaped the country’s massive financial meltdown was one founded and run by women, which leads into a discussion of the transformative benefits that have come with women gaining positions of power in government and business. Meanwhile, Iceland also differed from the U.S. in sending many of their financial bad boys to prison—an idea that the lead prosecutor says was modeled on America’s prosecution of malefactors in the savings and loan scandal.

That’s the kicker here. As he investigates one potentially useful idea after another, Moore keeps discovering that many originated in the U.S. Thus he’s not stealing from foreigners but reclaiming remedies that once belonged to us.

Anyone who travels abroad a lot inevitably reflects that, due to many factors, Americans are very insular, knowing far less about other countries than they know about us. Better national media and education might mitigate this, but in the meantime, Michael Moore has done thinking Americans a great service by opening several fascinating windows on the world. One of his most accomplished and entertaining films, “Where to Invade Next” is rich in ideas that deserve to be discussed by liberals, conservatives and everyone else on the political spectrum in the upcoming election year. Optimistic and affirmative, it rests on one challenging but invaluable idea: we can do better.