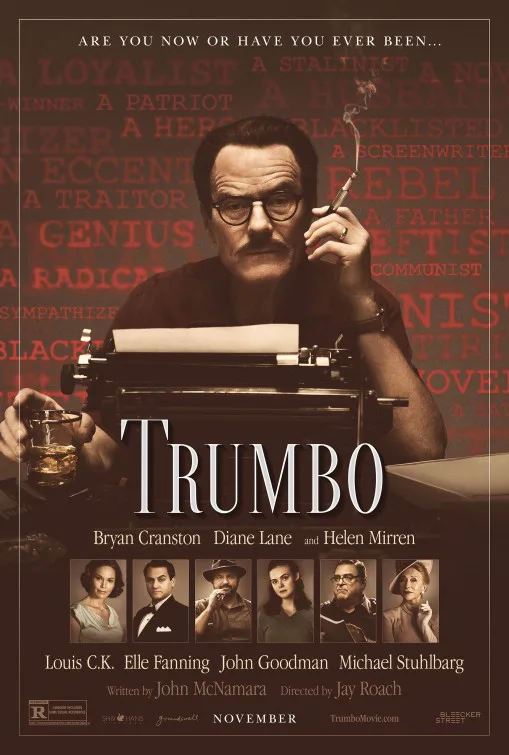

A ways into “Trumbo,” a TV-style biopic about blacklisted screenwriter Dalton Trumbo, it’s the late ‘40s and Bryan Cranston’s eponymous protagonist is in federal prison. He’s just had a ruinous appearance before the U.S. House Committee on Un-American Activities (HUAC), when he runs into J. Parnell Thomas (James DuMont), the former chair of that committee, who’s been convicted of income tax evasion. When the congressman remarks sardonically that they’re now in the same boat, Trumbo archly retorts, “Except that you committed a crime and I didn’t.”

Which tells you a lot about “Trumbo”: it’s another of those simplistic, made-to-order films about the Hollywood blacklist in which the blacklisted movie folks are all innocent, in every conceivable way. In fact, though, Trumbo was convicted of a crime: contempt of Congress, which involved refusing to answer even basic factual testimony to a committee embarked on a politically questionable but entirely lawful investigation.

The problem with reviewing a movie like “Trumbo” is that it comes after decades of misinformation and distortion that have left the public memory of the events it covers awash in rampant misperceptions. Take, as just one minor example, the DVD jacket copy on a recent documentary about Trumbo, which describes him as “among the ‘Hollywood Ten’ blacklisted by the House Un-American Committee in the 1940s for communist associations.”

As a statement of fact, that assertion would probably be accepted at face value by many folks. But HUAC never blacklisted anyone. Hollywood’s studio chiefs set up the blacklist after the 1947 hearings; for over a decade, it was a practice that most people in the industry either supported or didn’t openly resist. Trumbo himself, while allowing that he did indeed hold the 1947 Congress and some subsequent ones in contempt, was adamant in insisting that the U.S. government and its vicious right-wingers weren’t to blame for the blacklist—Hollywood was.

That’s one of the crucial points that somehow gets lost in “Trumbo,” which partakes of the same muddled mythology that has grown up around the blacklist since the 1970s. This mythology depends on various confusions and encourages others (e.g., that Sen. Joseph McCarthy had something to do with Congress’ pursuit of Hollywood; he didn’t). Above all, it invites us to the see the Communist Party USA as just another political party rather than as the domestic instrument of a hostile and ultra-murderous foreign tyranny.

Trumbo joined the Communist Party in 1943, when the US and USSR were allies. We never see anything of his activities in the party over the several years when he was a member. Rather, when the film opens in 1947, he’s a rich, super-successful screenwriter whose party membership gets him called in front of HUAC. Although the movie doesn’t explain why all members of Hollywood Ten adopted the same, ill-fated strategy of claiming the First Amendment (rather than the Fifth, which would keep subsequent witnesses out of jail), it shows they expect the Supreme Court to overturn their subsequent contempt-of-Congress convictions.

That doesn’t happen, so they all go to prison, where Trumbo learns that some members of the proletariat despise his communism as much as right-wingers like John Wayne do. Back in Hollywood thereafter—the movie elides the two years he spent in Mexico with three other screenwriters and their families—he’s obliged to support his family by writing screenplays under pseudonyms for low-rent producers such as the King brothers (played for laughs by John Goodman and Stephen Root). While engaging in this masquerade, he even manages to write “Roman Holiday” and “The Brave One,” which win Oscars that go to the “front” writers whose names were put on them.

Trumbo’s difficulties in surviving as a writer under the blacklist, and his efforts to break it, are the movie’s heart. His valiant wife Cleo (Diane Lane) and three school-age kids must deal with an existence built on a complex set of deceptions, and on the orneriness of a writer who does much of his work in the bathtub swilling booze and smoking. But Trumbo’s cussed perseverance pays off when Kirk Douglas enlists him to write “Spartacus” and Otto Preminger has him adapt “Exodus”—the movie’s most engaging section, these scenes point toward a victory for Trumbo that will also rescue others.

Jay Roach’s direction recalls the brisk efficiency of his TV dramas such as “Game Change” but seems uninterested in getting beneath the drama’s pat surface. Late in the movie, when Trumbo is an older man, we see a portion of the famous speech in which he declared that there were no heroes or villains in the blacklist story, only victims. The film doesn’t tell us that this heresy resulted in bitter acrimony from his communist colleagues any more than it shows us how Trumbo’s long-festering disillusionment with the party led to it. The film is full of such lapses in contextualization.

For example, missing is any sense of the utter contempt that Trumbo and his communist cohorts felt for liberals, who, in fact, they often regarded with more enmity than they did right-wingers. But that makes sense, of course. The communists were hoping for a revolution to overthrow American democracy. A takeover by fascists would only hasten that result, they thought; successful liberalism could only impede it.

Cranston’s portrayal of Trumbo gets much of his determined crankiness, but misses his cheeky exuberance and famous joie de vivre; too often, he simply seems dyspeptic. But most of the characters in John McNamara’s script are drawn in simple strokes, and that’s one of the movie’s biggest problems. Setting up a political drama in stereotypical black-hat/white-hat fashion results in enjoyably cartoonish villains like flamboyant gossip columnist Hedda Hopper (deliciously played by Helen Mirren) and the usual blacklist martyrs, but it also deprives the story of the nuance and complexity for which it cries out.