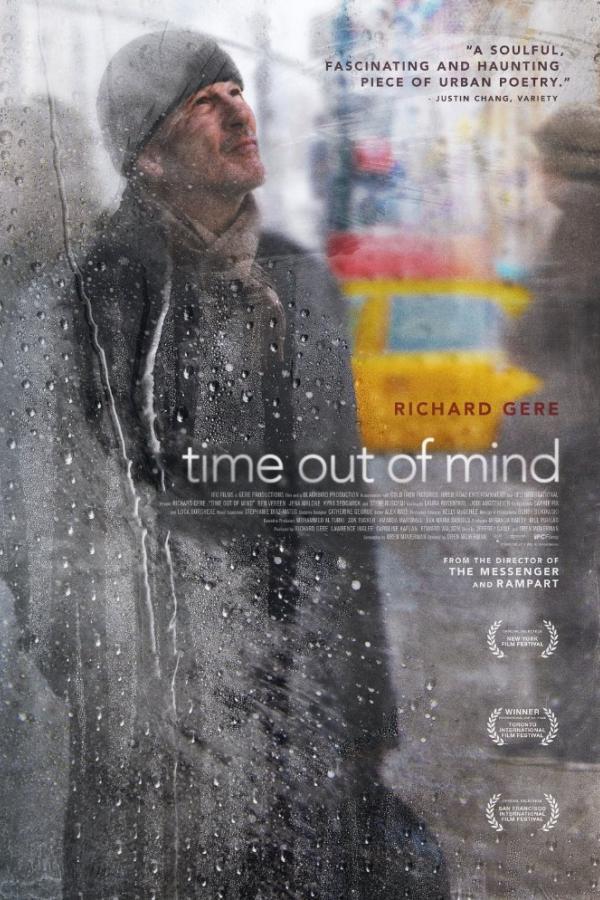

Oren Moverman’s “Time out of Mind,” about a homeless and probably mentally ill man trying to survive in New York City, does not feel like a typical American independent drama made in this century. It’s set in harsh reality and shot with a simplicity and directness that demands the viewer’s full attention. And it is built around a lead performance by Richard Gere that immediately draws the viewer in through familiarity (or star power) but then increasingly demands that we engage with the character on his own terms, and forget whatever we think we know about the actor.

The movie starts with Gere’s character, George, being surprised while squatting in an apartment. The building manager (Steve Buscemi, one of many name actors who play one or two scenes in the film) reluctantly tells him that he can’t stay there anymore. George says he’s waiting on “her.” In time we understand that he’s talking about his daughter Maggie (Jena Malone), who kicked George out, again for unspecified reasons, though probably for drinking (in one brief sequence where George comes into a bit of cash, he spends it on a six pack and drinks it all at once). Eventually he ends up at a bleak, racially tense homeless shelter where he’s befriended by Dixon (Ben Vereen), a former jazz man who has a dozen synonyms for every noun and speaks in the relentlessly upbeat cadences of a scam artist even when he’s being entirely sincere. He has more experiences, and while we feel sure that the movie is edging toward a destination, we can tell by the tone and style that it’s not going to be a typically upbeat one, with lessons learned and problems solved.

“Time out of Mind” is an observational film, mainly concerned with behavior rather than story. You hear the characters’ names in passing, and if you’re not paying attention you might not hear them again. This is not the kind of movie where a character walks into a room and says how glad they are to see their friend George whom they haven’t spoken to since that chance encounter in Queens almost seven years ago. Very rarely do the characters come right out and tell you exactly who they are or what happened to them or what they would like to happen to them.

Instead, Moverman puts us in the position of an eavesdropper or secret spectator throughout. The only music is provided by the PA systems of restaurants, bars and coffee shops, the speaker systems of passing cars, and occasional snatches of street music, such as the saxophone player who is heard (but not seen) in a brief scene set on a subway car. Watching “Time Out of Mind” is not like the ordinary experience of watching a movie; it’s more like being in a public place and deciding to allow the scene around you to become a drama.

We sometimes have to locate George in a shot, like Waldo in the popular children’s books. Sometimes Moverman will pack the character into a door frame in the deep background of a shot, or look down on him from a third-story window as he crosses a street. When we do get closeups of George they often have the feel of having been “stolen”—a word that independent filmmakers use to describe shots that are obtained without a permit from any authority, often from far away, with a telephoto lens, so that the actor is simply part of the landscape, and the real people around him are unwitting extras. Moverman did in fact shoot parts of “Time Out of Mind” this way, and it has the effect of situating us within George’s headspace (he’s just one New Yorker among many) and also creating a visual correlative for the idea behind the film: that people like George are, for all intents, invisible, a notion that becomes achingly clear as we see people pass him, or look past him, while going about their lives.

Gere’s performance is almost entirely reactive, and this makes you appreciate his charisma all the more. There aren’t many actors who can sustain a whole film just by sitting silently and thinking and occasionally saying something simple like “Yes” or “I can’t remember.” Gere is one of them. I suppose there are viewers who will be unable to accept him in this role because he’s still Richard Gere, Handsome Movie Star, and dismiss this as a “vanity project,” but that will be entirely their decision. This is as affecting a portrait of loneliness by a grey-haired onetime hunk as Clint Eastwood’s work in “Gran Torino“—a film that, unlike “Time Out of Mind,” never rose to the level of its lead performance.

Some of the most unusual and startling moments in the movie come about because Moverman and cinematographer Bobby Bukowski capture a moment by choosing a shot and staying with it. A lot of times they park the camera on Gere’s face in closeup (sometimes head-on, sometimes in profile) as he tries not to let on that he’s affected by a loud drama occurring adjacent to his silent one: a man having a meltdown while security guards try to escort him away from the scene of a fracas; a bunkmate at the shelter talking about the Bible and his job. In one of the film’s many, extraordinary one-take scenes, we watch through a window covered by a metal screen while George eats a meal at a long table in the shelter’s mess hall. Suddenly the man next to him reacts with alarm, then stands up and takes his plate and walks away as a mouse scampers across the table. George keeps eating.

There’s a moment where George goes to spy on Maggie at her bartender job. He stands out on the street for a bit, watching her through a window, then approaches a young man who’s standing on the sidewalk smoking a cigarette and talking on his cell phone to a young woman he hopes will have sex with him. Moverman gives us about a minute of this other man’s story (revealed via the one-way conversation) while George waits for the right moment to approach and ask if the man could please go inside and deliver some photos to Maggie. It’s the sort of scene that happens all the time in cities (though more often the request is, “Can you spare a quarter?”) without anyone thinking about the sorrow that underlies it, and the inequity it reveals.

The movie is probably too long; there are scenes that repeat points that were made a few scenes earlier, and moments where the dialogue verges on too-expository, as well as times when the framing seems less considered than fussed-over (a shot of a homeless shelter counselor as seen through the open window of a transom is just too much). But such moments are notable because of their scarcity. With certain rare exceptions—the early films of Ramin Bahrini; Lodge Kerrigan’s “Keane” from ten years ago; the current “Tangerine“—American movies almost never tell stories about people this far down on the socioeconomic ladder, in a literally down-to-earth style that treats the world as a stage and roots each gesture in observed reality.

Moverman, the director of the Iraq war drama “The Messenger” and the cop corruption thriller “Rampart,” is three for three now. This is the best movie he’s made, and the least beholden to commercial filmmaking norms. There are times when it gets close to turning into an American version of the sorts of stark yet tender dramas made by the Dardenne brothers in Belgium. What’s the commercial value of a film like this? Probably nada, unless Gere and Vereen pick up a few critics’ awards. But a big part of the film’s power comes from the feeling that the filmmakers don’t care about any of that. “Time out of Mind” seems to have been undertaken for no other reason than that the filmmakers and actors believed in the truth of the material. How many American movies can you say that about?