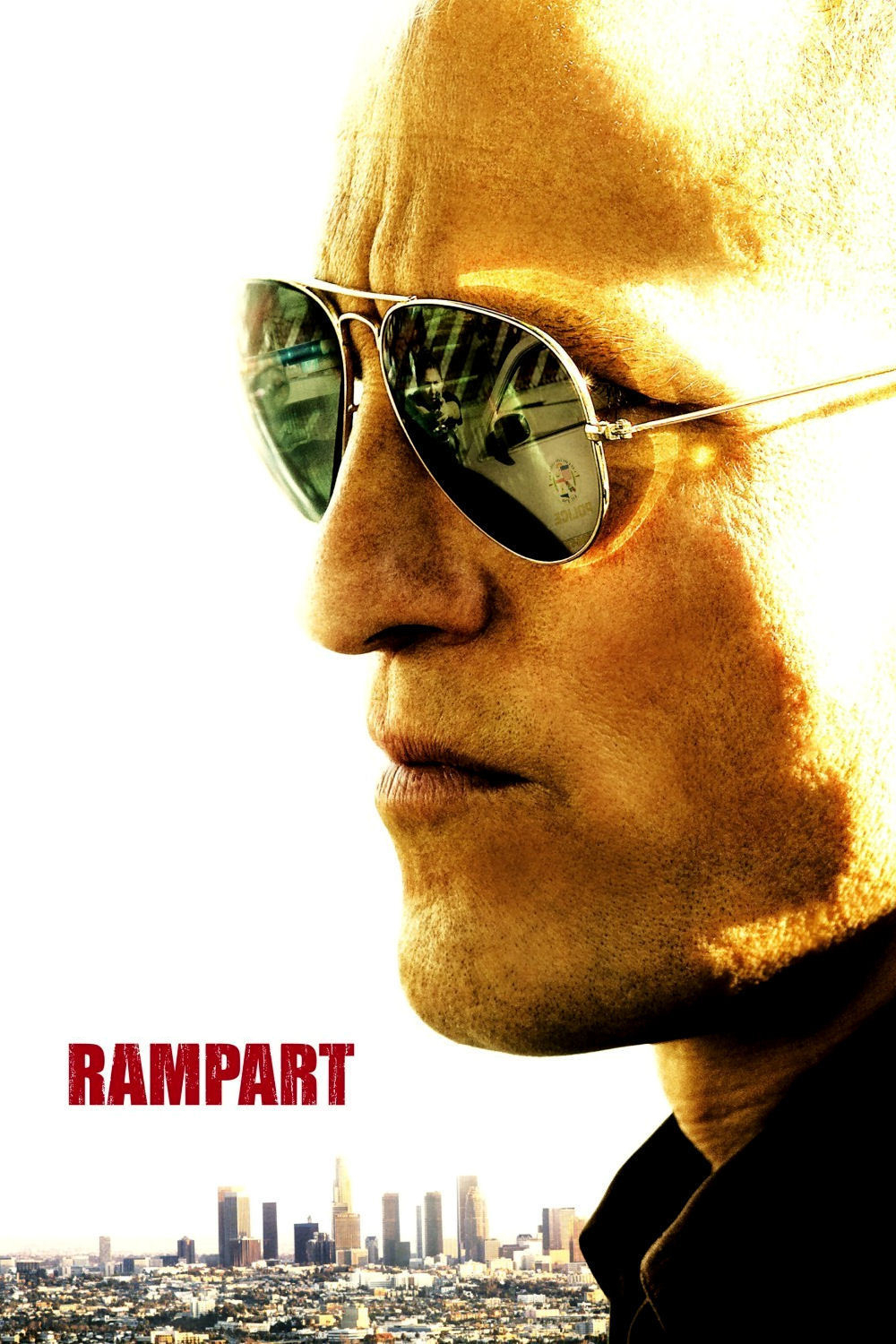

Woody Harrelson is leaner in “Rampart,” the skin tight over the skull, the jawline defiant. His eyes are busy. He is a cop in the Los Angeles police district that became notorious in 1999 as a cesspool of corruption, but this man takes corruption with him wherever he goes. The movie is co-written by the unsurpassed crime writer James Ellroy, who no doubt knows enough stories about Rampart to write a dozen movies, but his inspiration here is to make this cop a stand-alone character study, isolated within himself. He doesn’t require the reprehensible environment of Rampart. He’s self-fueled.

Harrelson is an ideal actor for the role. Especially in tensely wound-up movies like this, he implies that he’s looking at everything and then watching himself looking. His character, Dave Brown, has no moral center, but he has the survival instincts of a rat, and I say that with all due respect for rats. He always likes to know the way out of a tight corner. He knows an angle he can play or a squirm he can call on.

Why is he this way? That question helps explain why the movie is so absorbing, because there is no answer. “Rampart” lacks the usual plot engines behind crime films, in which motivation comes from money, lust or revenge. Brown behaves in this film primarily just to do bad things.

He reminds me of one of the most evil characters in American fiction, Judge Holden in Cormac McCarthy’s Blood Meridian, a man who likes to torture and kill for no other reason than simply to cause pain. The Harrelson of “Rampart” could play Judge Holden, and not many actors could.

He is an overt racist. He has such contempt for women he cannot always be bothered to use them sexually. He was married to two women (Anne Heche and Cynthia Nixon) who are sisters, and apparently this meant so little to all of them that they live in houses next to one another. There was no emotional commitment there for them to engage. He has a daughter by each and is said to have once murdered a rapist because of his feelings for his daughters. Only with a man like Brown would you suspect that was an excuse; more likely, he got started killing the man and didn’t feel like stopping.

It’s that feeling that seems to empower Brown when he does the last thing Rampart district needs in 1999. Eight years after the brutality against Rodney King, Brown is videotaped while beating a suspect. He seems to approach this task like a skilled workman performing a job he loves. Recently there’s been a movement to make videotaping of police officers illegal. That would get Dave Brown’s vote.

This time he doesn’t seem to have an escape route ready. The district attorney’s office sees him as an ideal target, and Sigourney Weaver is finely focused as an assistant DA who has him in her sights. He also makes the error of trying to pick up a defense attorney (Robin Wright) in just the wrong way at just the wrong time. And he casually insults a black investigator for Internal Affairs (Ice Cube).

“Rampart” is deeply embedded in Los Angeles in the summertime, every day a reminder of the desert that waits patiently to take back the land stolen from it by sprinkler systems. It is hot, the sun is blinding, Brown is sweating, he feels rotten. You cannot live forever with amorality and sadism eating away at you. Even other immoral people around you stand back, because they recognize themselves and fear to go that far.

“Rampart” was directed and co-written with Ellroy by Oren Moverman, whose directorial debut was “The Messenger” (2009). He was nominated for an Oscar for that screenplay. It also starred Woody Harrelson, playing an Army veteran whose job is to inform the next of kin that a soldier has been killed. He’s training his new partner on the job and advises him not to take it personally: Don’t have physical contact with anyone, let alone hug them. Better for you, better for them. These are their lives. They need the news, not a new best friend.

In that film, Harrelson’s character turns out to have feelings after all. He’s such a versatile actor, able to point one way and act in another. We know he can do that, and maybe that’s why he’s so fascinating in “Rampart.” Is it really possible for a man to be as evil and indifferent as Dave Brown, and be empty inside? Apparently so. What made him that way? Maybe nothing did. Maybe it’s just the way he is.