I would like to grow up to be like Clint Eastwood. Eastwood the director, Eastwood the actor, Eastwood the invincible, Eastwood the old man. What other figure in the history of the cinema has been an actor for 53 years, a director for 37, won two Oscars for direction, two more for best picture, plus the Thalberg Award, and at 78 can direct himself in his own film and look meaner than hell? None, that’s how many.

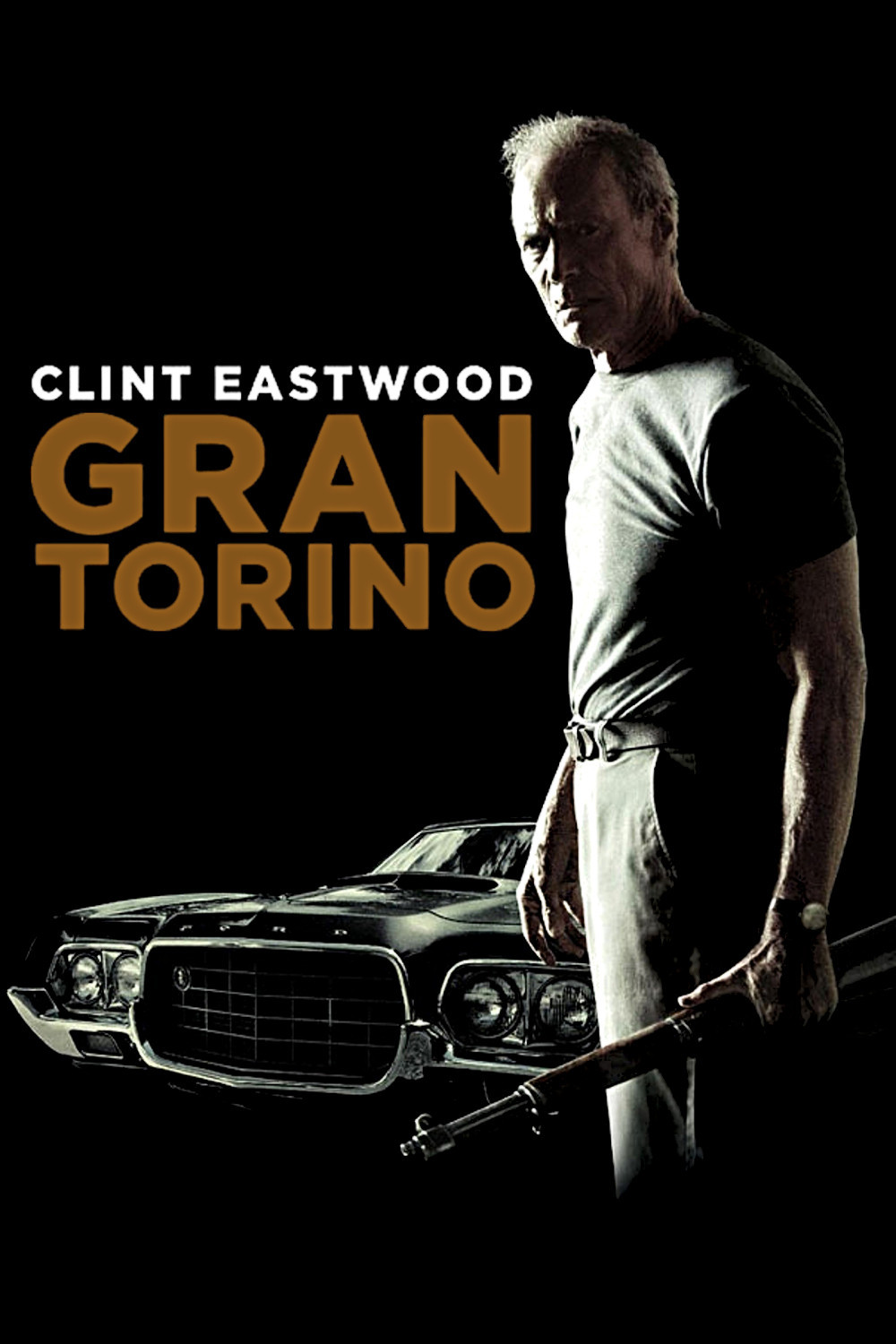

“Gran Torino” stars Eastwood as an American icon once again — this time as a cantankerous, racist, beer-chugging retired Detroit autoworker who keeps his shotgun ready to lock and load. Dirty Harry on a pension, we’re thinking, until we realize that only the autoworker retired; Dirty Harry is still on the job. Eastwood plays the character as a man bursting with energy, most of which he uses to hold himself in. Each word, each scowl, seems to have broken loose from a deep place.

Walt Kowalski calls the Asian family next door “gooks” and “chinks” and so many other names he must have made it a study. How does he think this sounds? When he gets to know Thao, the teenage Hmong who lives next door, he takes him down to his barber for a lesson in how Americans talk. He and the barber call each other a Polack and a dago and so on, and Thao is supposed to get the spirit. I found this scene far from realistic and wondered what Walt was trying to teach Thao. Then it occurred to me Walt didn’t know it wasn’t realistic.

Walt is not so much a racist as a security guard, protecting his own security. He sits on his porch defending the theory that your right to walk through this world ends when your toe touches his lawn. Walt’s wife has just died (I would have loved to meet her,) and his sons have learned once again that the old bastard wants them to stay the hell out of his business. In his eyes, they’re overweight meddlers working at meaningless jobs, and his granddaughter is a self-centered greed machine.

Walt sits on his porch all day long, when he’s not doing house repairs or working on his prized 1972 Gran Torino, a car he helped assemble on the Ford assembly line. He sees a lot. He sees a carload of Hmong gangstas trying to enlist the quiet, studious Thao into their thuggery. When they threaten Thao to make him try to steal the Gran Torino, Walt catches him red-handed and would just as soon shoot him as not. Then Thao’s sister Sue (Ahney Her, likable and sensible) comes over to apologize for her family and offer Thao’s services for odd jobs, Walt accepts only reluctantly. When Sue is threatened by some black bullies, Walt’s eyes narrow and he growls and gets involved because it is his nature.

What with one thing and another, his life becomes strangely linked with these people, although Sue has to explain that the Hmong are mountain people from Laos who were U.S. allies and found it advisable to leave their homeland. When she drags him over to join a family gathering, Walt casually calls them all “gooks” and Sue a “dragon lady,” they seem like awfully good sports about it, although a lot of them may not speak English. Walt seems unaware that his role is to embrace their common humanity, although he likes it when they stuff him with great-tasting Hmong food and flatter him.

Among actors of Eastwood’s generation, James Garner might have been able to play this role, but my guess is, he’d be too nice in it. Eastwood doesn’t play nice. Walt makes no apologies for who he is, and that’s why, when he begins to decide he likes his neighbors better than his own family, it means something. “Gran Torino” isn’t a liberal parable. It’s more like, out of the frying pan and into the melting pot. Along the way, he fends off the sincere but very young parish priest (a persuasive Christopher Carley), who is only carrying out the deathbed wishes of the late Mrs. Kowalski. Walt is a nominal Catholic. Hardly even nominal.

“Gran Torino” is about two things, I believe. It’s about the belated flowering of a man’s better nature. And it’s about Americans of different races growing more open to one another in the new century. This doesn’t involve some kind of grand transformation. It involves starting to see the “gooks” next door as people you love. And it helps if you live in the kind of neighborhood where they are next door.

If the climax seems too generic and pre-programmed, with too much happening fairly quickly, I like that better than if it just dribbled off into sweetness. So would Walt.