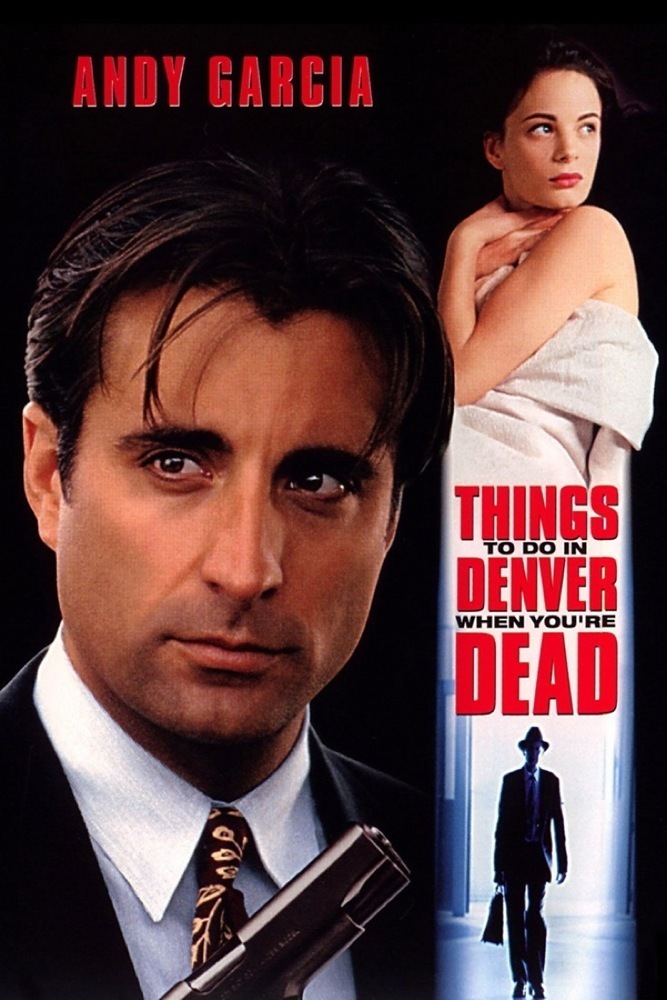

I’ve been back and forth on “Things to Do in Denver When You’re Dead.” At the 1995 Cannes Film Festival, I thought it had more spirit and audacity than most of the films in a slow year. But then, seeing it again, I found myself focusing on its cuteness and contrivance: It’s so overwritten it becomes an exercise in style rather than a story about its characters. On balance, I think it’s an interesting miss, but a movie you might enjoy if (a) you don’t expect a masterpiece, and (b) you like the dialogue in Quentin Tarantino movies.

I hasten to add that “Things to Do in Denver When You’re Dead” has apparently not been directly influenced by Q. T. When I suggested in a dispatch from Cannes that it was “Quentonian” (or should it be “Tarantinesque”?), I got a note from Gary Fleder, who directed it, pointing out that the screenplay by Scott Rosenberg was written long before “Reservoir Dogs” saw the light of day.

I can believe that. Rosenberg’s screenplay, however, probably springs from some of the same impulses that inspired Tarantino. The characters talk like they were raised on 1940s noir movies, and then given a quick course in advertising copywriting. Every other line sounds like a would-be catchphrase: “Most girls, they plod. You glide along.” “I want you to brace this guy.” “I lost a toe the other day.” “Maybe not today and maybe not tomorrow, but someday soon.” Sorry – that one’s from “Casablanca.” But Andy Garcia uses it here.

As the movie opens, Jimmy the Saint (Garcia) is running a service where dying people can videotape advice to their loved ones.

(“Treat them like dirt, and they come running,” one dad tells his son about women.) The service is losing money, and the notes are held by the Man With the Plan (Christopher Walken), a right-wing homophobe who runs the Denver crime scene from his breath-powered wheelchair (one wonders exactly where Walken would begin if he ever wanted to satirize himself).

The MWTP will forgive the debt, if Jimmy the Saint does a job for him. The Man’s son has been charged with child molesting after a daylight raid on a school playground, and the Man thinks he might settle down if he got his old girlfriend back. Therefore, Jimmy’s job is to intercept the old girlfriend’s new boyfriend on his way into town, and “brace” him.

Jimmy is a former criminal, now trying to go straight, but he’s forced to take the job. So he rounds up some old associates who make Tarantino’s reservoir dogs look like brush salesmen. They include Critical Bill (Treat Williams), who hasn’t beaten up a live person in years – “not since I found myself that exercise program,” which consists of beating up corpses in the morgue; Pieces (Christopher Lloyd), a porno projectionist with leprosy, whose toes and other parts are falling off, and Franchise and Easy Wind (William Forsythe and Bill Nunn), who are marginally more mainstream.

Can these five guys “brace” the boyfriend? They devise a plan worthy of the Brinks Job, including a stolen police cruiser and the impersonation of police officers. Unfortunately, the boyfriend isn’t too impressed by Pieces when he’s hauled over on the road into town.

In the movie’s funniest scene, he wonders why the police department hasn’t issued him a rain hat, and then notices the missing fingers and calls the bluff (“Tell me, Officer Leper . . .”).

The movie has not one but two romances, both involving Jimmy the Saint. He falls hard for Dagney (Gabrielle Anwar) in a bar, smelling her hair and informing her, “Girls who glide need guys to make them thump.” But when the situation gets dangerous, he returns to an old friend, Lucinda (Fairuza Balk), a hooker with a face like a wounded Judy Garland – but a heart, of course, of gold.

All of this action is carefully monitored from a local diner by a retired hood named Joe (Jack Warden). He supplies sort of a Greek chorus of commentary on the action, not really necessary, although it provides for dialogue while Jimmy the Saint is gulping down milk shakes for his bad stomach.

“Things to Do in Denver When You’re Dead” is not a successful movie on its own terms. It’s too cute and talky, and too obviously mannered to develop convincing momentum. But as an exercise it’s sometimes funny and always energetic, and it shows that Rosenberg can write and Fleder can direct. Now if they can just dial down a little.