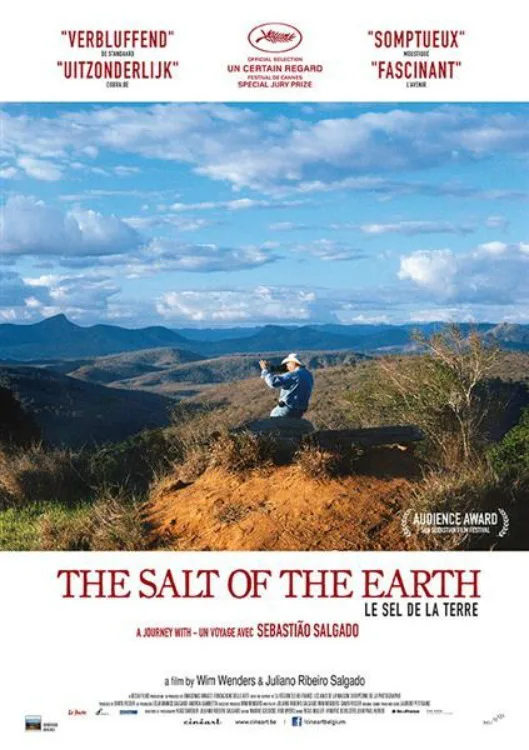

Although best known as the director of such celebrated films as “Kings of the Road,” “Paris, Texas,” “Wings of Desire” and “Until the End of the World,” filmmaker Wim Wenders has also carved out a second career for himself as a documentarian with a special focus on artistic endeavors and the people behind them. Over the years, he has taken a look at such diverse subjects as the life and work of directors Nicholas Ray (“Lightning Over Water”) and Yasujiro Ozu (“Tokyo-Ga”), fashion designer Yohji Yamamoto (“Notebooks on Cities and Clothes”), musical history past and present (“Buena Vista Social Club,” “Ode to Cologne: A Rock ‘N’ Roll Film” and “The Soul of a Man”) and choreographer Pina Bausch (“Pina”). For his latest documentary, “The Salt of the Earth,” one of the nominees for this year’s Oscar for Best Documentary, Wenders trains his camera on photographer Sebastiao Salgado and the result, though not without flaws, is an invigorating and interesting observation of the man, his work and the entire medium of photography.

As the film reveals, the Brazilian-born Salgado originally studied economics and worked for the World Bank in France after being exiled from his home country in 1969, before deciding to give it all up in order to pursue a career in photography. After his first major project, a photographic chronicle of South America that allowed him to at least get near to his homeland (his exile would eventually end in 1980), he began a series of expansive projects in which he used his keen eye and ability to create striking images to create works that allowed viewers to bear witness to glimmers of hope and humanity in the face of almost unimaginable misery. “The Workers,” for example, famously illustrated such locations as a massive Sierra Pelada mine and the countless people employed to dig out the gold in the hopes that their back-breaking labor will one day pay off and the burning oil fields of Kuwait in the wake of Desert Storm. “Sahel,” which he produced in conjunction with Doctors Without Borders, looked at the famine in Ethiopia and the attempt by many to journey to what they hoped to be a better life in the Sudan. In a similar vein, “Exodus” looked at the plight of refugees from Rwanda and Yugoslavia during their respective troubles in the Nineties.

Having “seen into the heart of darkness” (as Wenders puts it in his occasionally purple narration) for so long, a burned-out Selgado returned to Brazil to the drought-stricken remains of his family’s once-thriving farm and embarked on a plan of replanting and reviving the land that he dubbed “Instituto Terra.” Not only did this effort help begin to bring the farm back to life, it would spread, first to other parts of Brazil and then worldwide. It would also lead to Salgado’s most recent project, a collaboration with son Juliano (himself a documentarian who receives a co-directing credit here) entitled “Genesis” that took them from Papua New Guinea to Siberia to chronicle lands and people who have managed to retain their natural ways in the face of the planet’s seemingly unstoppable march towards destruction that stands in blessed relief to the horrors he had shown in the past.

One of the challenges that any documentarian must face in making a film about an artist in a particular field is to figure out a way to channel that person’s craft into meaningful cinematic terms while still remaining true to the work being examined. Wenders pulls this off through a couple of fascinating artistic choices. While the black-and-white cinematography (Juliano Selgago shot the color footage) that he employs may not be that surprising to fans of his work (it is a choice that he has employed with great skill over the years, especially in the visually stunning “Wings of Desire”), his use of it this time around in collaboration with cinematographer Hugo Barbier certainly evokes the similarly monochromatic look of Salgado’s work, especially in the distinct methods of employing light, shadow and space in the compositions. Another striking idea that Wenders deploys here is to project several of Selgado’s most famous images in a way that allows Selgado’s face to appear to emerge from the works themselves as he offers up memories of those particular shoots.

I do have a couple of quibbles with “The Salt of the Earth,” however. For one, while it does make a strong case for Salgado’s undeniable artistic achievements, it does not really go into the nuts and bolts of his process—there is nothing to speak of regarding his photographic influences or how he actually goes about capturing his images. More troublingly, although some critics have charged him with transforming the miseries of the Third World into attractive images for Westerners to gaze at in art galleries, there is no discussion of the moral and ethical repercussions of his work to be had here. Although they do not fatally damage the film as a whole, their absence does leave a bit of a hole at the center of the proceedings that cannot be denied. For the most part, however, “The Salt of the Earth” is a visually stunning and oftentimes affecting tribute to one artist from another.