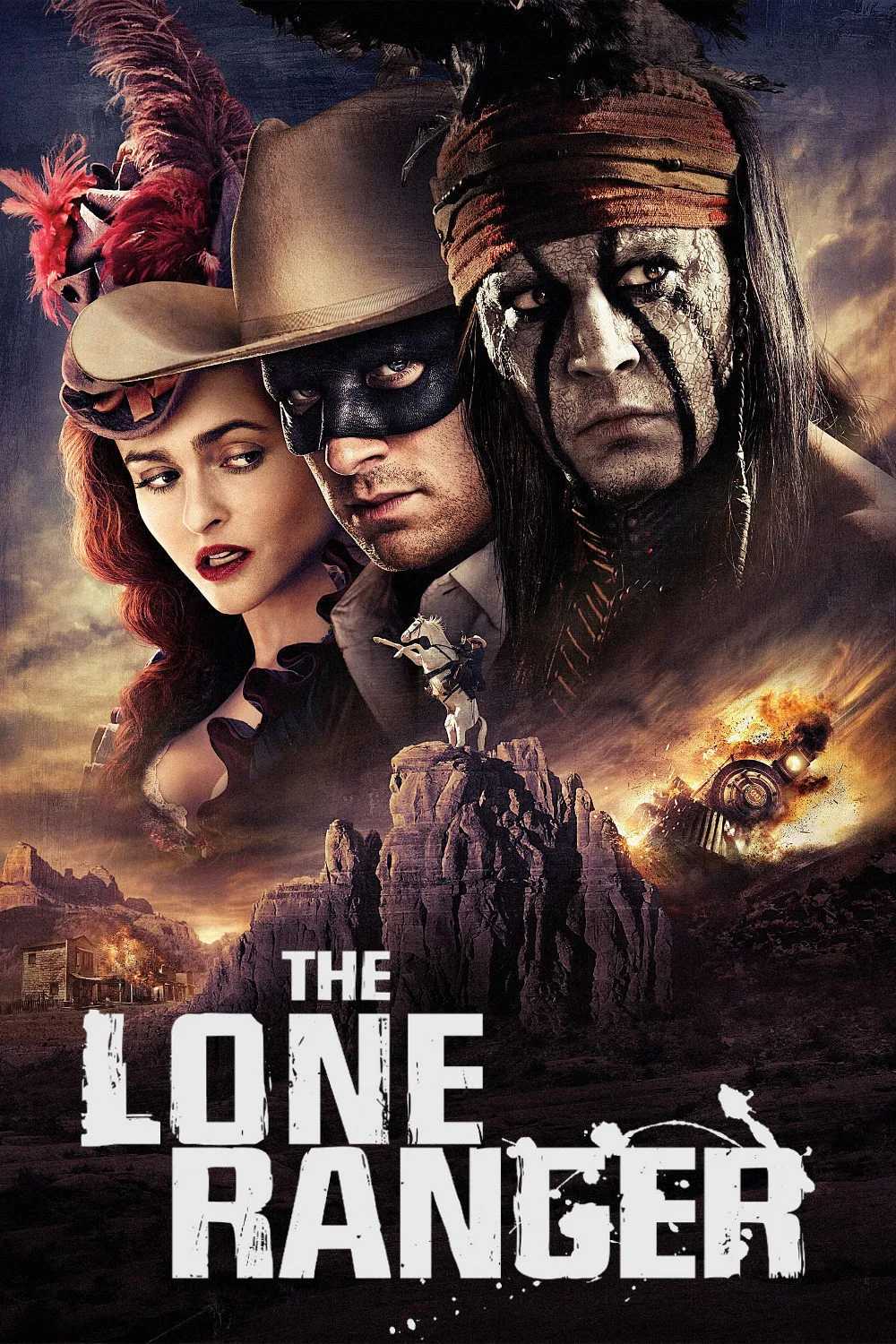

Like “Speed Racer” and “John Carter” before it, “The Lone Ranger” is a movie with no constituency to speak of. It’s a gigantic picture with a klutzy, deeply un-cool hero (Armie Hammer of “The Social Network“), based on a property that most young viewers don’t know or care about. It arrives in theaters stained by gossip of filmmaker-vs.-studio budget wars, and concerns that its star and co-executive producer, Johnny Depp, would play the Ranger’s friend and spirit guide, Tonto, as a Native American Stepin Fetchit, stumbling around in face-paint and a dead-crow tiara. The film’s poster image might as well have been a target. Too bad: for all its miscalculations, this is a personal picture, violent and sweet, clever and goofy. It’s as obsessive and overbearing as Steven Spielberg’s “1941” — and, I’ll bet, as likely to be re-evaluated twenty years from now, and described as “misunderstood.”

This time out, Tonto doesn’t live to serve the Masked Man. He’s a wandering spirit on his own mission of justice, disillusioned and driven mad by pain he endured decades ago. The Ranger, whose birth name is John Reid, has gone west to join his Texas Ranger brother (James Badge Dale, who’s in every other blockbuster these days). Reid meets Tonto shackled on a train with the repulsive outlaw Butch Cavendish (William Fichtner), who escapes, links up with his old outlaw gang, and wreaks havoc on Reid, Tonto and the territory — but not in a vacuum. Butch may be a leering, scar-faced sadist who eats human flesh — Tonto refers to him as “wendigo”, says he’s driven “life out of balance” a la the “Koyaanisqatsi” poster’s catchphrase, and carries a silver bullet to put him down — but in time we see that the outlaw is an expression of the American id. Like the railroad baron (Tom Wilkinson) that he secretly serves, Butch expresses the will of the majority, even though the kindlier members of the majority hate to think of themselves in such unflattering terms.

The film portrays its setting as a PG-13 version of Sergio Leone and Clint Eastwood’s every-man-for-himself hellscape. Granted, this has been the Western’s default worldview since the seventies, but it’s still startling to see it applied to “The Lone Ranger.” This myth is innately square, attuned to received wisdom about who runs the country and why it’s okay. The character tried to migrate from the 1950s small screen to theaters in 1981 and failed, not just because the movie was weak, but because seven years after Watergate and six years after the fall of Saigon, the notion of a poor person of color devoting himself to a middle-class white male savior didn’t make sense anymore, if indeed it ever did. (Intriguingly, there’s evidence that the real-life basis for the Ranger was a black man.) How do you adapt the Ranger for multicultural, post-9/11, post-financial-meltdown America? That’s the question. The filmmakers grapple with it amusingly, and throw in large-scale action, broad slapstick, and black-comedy banter while they’re at it. (“The United States Army!” Reid exclaims at one point. “Finally, someone who’ll listen to reason!”)

There were points when the picture reminded me of the first three Indiana Jones films, and not just because the climax involves runaway trains on parallel tracks and the bad guy removes a man’s heart from his chest (an atrocity reflected and abstracted in a witness’s eyeball). Like the Indy films—and like “Silverado,” which had a Spielbergian sensibility even though Spielberg didn’t direct it—this “Ranger” is an overproduced cliffhanger, and it’s very 20th century in its methods. The film’s director, Gore Verbinski, thinks about what’s in the frame and what’s out, and about when the camera will move, and why. (Keep an eye out for the pan-up from Helena Bonham Carter’s one-legged brothel madam to the portrait of her character as a young woman.) And in an age in which most blockbusters have but one mode, the steroid-pumped sprint, this “Ranger” gives its characters space to breathe and think—too much time, honestly, as the movie’s convoluted, stop-and-start midsection hurts its momentum; but still!

Hammer has the earnest, bumbling beauty of young Christopher Reeve. His character’s arc blends the Jimmy Stewart and John Wayne characters from “The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance“, the bookish pacifist becoming a humble, practical-minded gunman who’s appealing enough to entice his brother’s plucky widow (Ruth Wilson, underused, as women in summer action films tend to be). Tonto’s sad backstory and eccentric behavior are Jack Sparrow-like, but the performance owes more to stone-faced silent movie stars such as William S. Hart and Buster Keaton. Not that viewers will care after twenty-plus years of Depp’s mugging, but this is his best Zen clown act since “Benny & Joon.”

The movie’s crazy-quilt of references includes “Dead Man,” “El Topo,” “Blazing Saddles,” “The Searchers,” “A Man Called Horse,” the Man with No Name trilogy, Verbinski’s own “Rango,” the cinematic contraptions of Sam Raimi and Tim Burton (check out Bonham-Carter’s ivory leg-cannon!), and Keaton’s train-crazy “The General.” (There’s a “General”-worthy shot of Tonto perched on a long ladder that’s balanced across a locomotive like a seesaw.) The screenplay’s silliest conceit—Tonto telling Reid he “cannot be killed’ because he already died in the canyon—ties “The Lone Ranger” in with its releasing company, Walt Disney. The Ranger is Dumbo, Tonto is the mouse Timothy, and the hero’s nonexistent invincibility is the Magic Feather!

Luckily, “The Lone Ranger” is more than the sum of its references, because Verbinski and his screenwriters wind them around the core of a vision. This is a story about national myths: why they’re perpetuated, who benefits. As we watch this story unfold, we’re not seeing “reality,” but a shaggy, colorful counter-myth, told by a “Little Big Man”-looking elderly Tonto to a white boy at an Old West museum in 1933 San Francisco. Old Tonto is a “Noble Savage” in a glass case, surrounded by a Monument Valley diorama whose color and texture prepare us for the CGI-infused storybook landscapes of the film itself. Tonto wants to stop that boy from swallowing the official version of How the West was Won, and from reflexively trusting authority of any kind, ever. All the old Western signifiers are flipped. A U.S. Army action on behalf of a corporation is so cynical that the audience prays for Indians to ride to the rescue. The film is so attuned to Tonto’s distress that when a brass band plays “Stars and Stripes Forever”, it’s bad guy music, as chilling as the German national anthem in a World War II flick.

This Lone Ranger is a decent man from the start, but he’s serving corrupt masters without knowing it. By the end, his values are that of a brawny 1960s activist who insists that the stated values of America are great, but we haven’t lived up to them. As film critic Walter Chaw put it, this movie’s “a labor of love for a character so unbelievably square that he becomes symbolic of our disappointment in ourselves.” By the end, the Ranger has become something close to an American Robin Hood — an outlaw-by-circumstance who understands the difference between brute force and true moral authority. That such concepts are being endorsed by a $200 million Walt Disney tentpole picture will seem either hypocritical or inspiring, depending on whether you like the movie. Either way, this is a lumpy bubblegum blockbuster with a bitter aftertaste, overlong but dazzling, built of borrowed bits yet defiantly its own thing.