Walking home after the second Western was over at the Princess Theater, we’d play the roles we had seen on the screen. We were 7 or 8 years old at the time, but we didn’t have the slightest difficulty in identifying with the cowboys in the movies. All of their motives were transparently clear to us – except, possibly, why anyone would want to kiss a girl when he could be practicing his lasso tricks instead. The Westerns I remember from those days have been filtered through a golden haze of time, but the one thing I am sure I remember correctly is that they were fun. They were high-spirited, joyous, anarchic movies in which overgrown adolescents jumped on their horses and whooped and waved their hats in the air, and rode as fast as the wind to the next town and the next adventure.

“Silverado” is a Western like that. I mean the comparison to be praise. This movie is more sophisticated and complicated than the Westerns of my childhood, and it is certainly better looking and better acted. But it has the same spirit; it awards itself the carefree freedom of the Western myth itself – the myth of a nation “endlessly realizing Westward,” as Robert Frost had it, with limitless miles of prairie and desert and mountain interrupted only occasionally by a village with a church, six saloons and a Main Street wide enough for a dozen men to shoot at each other without all of them necessarily getting hit.

“Silverado” is the work of Lawrence Kasdan, the man who wrote “Raiders of the Lost Ark,” and it has some of the same reckless brilliance about it. It’s the story of four cowboys who join up together, ride into town, refuse to knuckle under to the corrupt sheriff and end up fighting for justice. This is a story, you will agree, that has been told before. What distinguishes Kasdan’s telling of it is the style and energy he brings to the project.

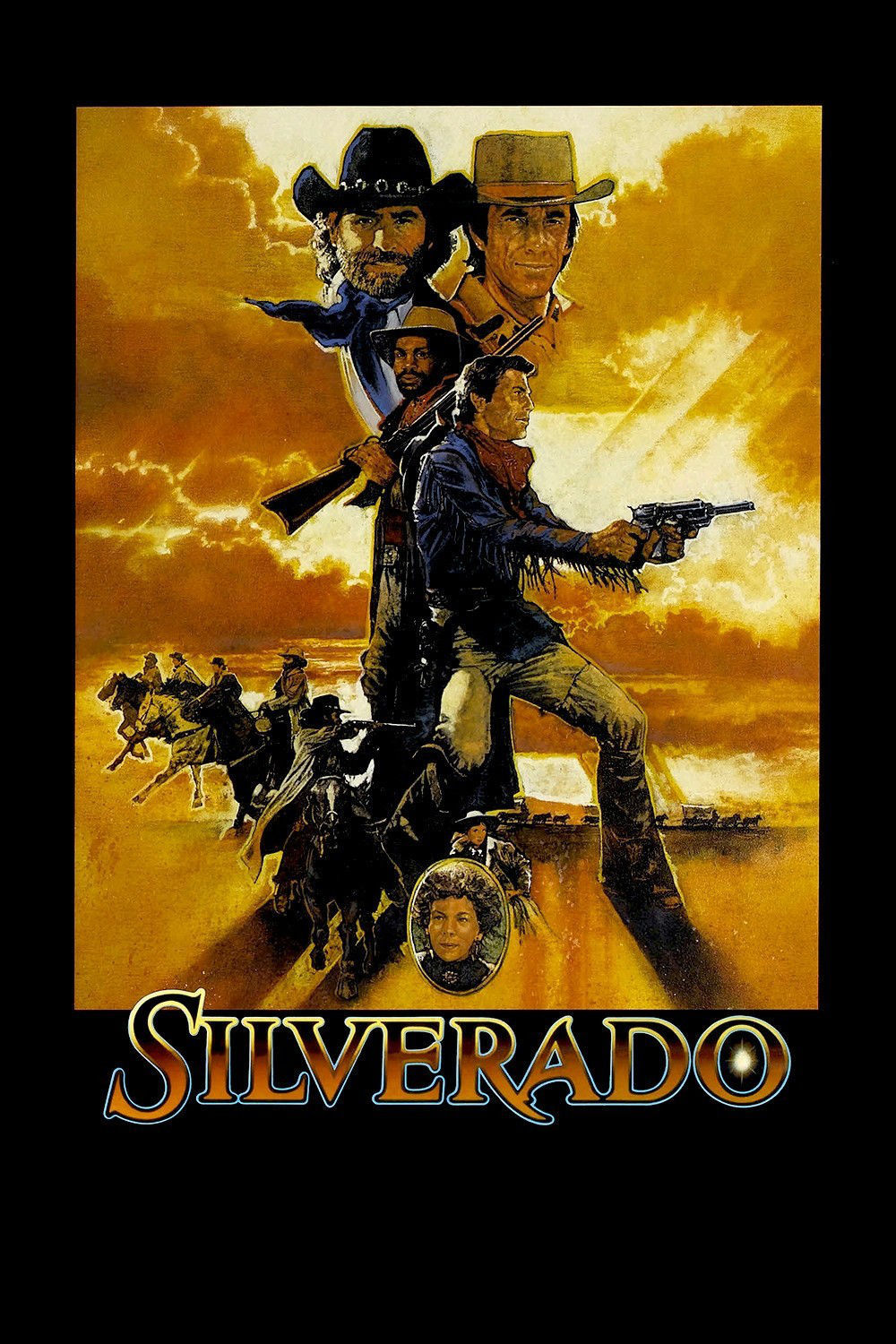

The cowboys include a sweet-faced young man who hopes to make his fortune (Kevin Kline), his goofy brother (Kevin Costner), a black man who vows to avenge his father’s murder (Danny Glover) and a taciturn loner (Scott Glenn) who gets restless when he’s not a long way from civilization. They meet along the way, after Glenn saves Kline from death in the desert, and together they help Costner escape from jail. Joining up with Glover, they ride on into the next town, Silverado, which is dominated by a slick sheriff (Brian Dennehy) and a gambling saloon run by a formidably competent little woman named Stella (Linda Hunt, in a scene-stealing performance).

I will not tell you too much of what happens next, but then perhaps I do not need to. If you are familiar with the Western, you will be familiar with this one. What may seem a little strange is that, if there is any nostalgia connected to this film, it will be found in our hearts and not in the characters on the screen.

Too many Westerns in the last 15 years have been elegies to a dead past, played out by actors remembering the cowboy roles of their youth (remember, if you can, the last Westerns of Robert Mitchum, Randolph Scott, John Wayne, Kirk Douglas). “Silverado” contains a group of talented young actors (Scott Glenn, the oldest, is in his 40s), and this is not their last Western but, in many cases, their first. The movie is set at the time when the West was still being opened up, when there was still opportunity there and when the bad guys were still so unsophisticated that they could fall for a dumb trick like getting trapped in a box canyon.

What does it prove, this movie about a bunch of cowboys held together by honor, this movie about bartender philosophers, evil sheriffs and young pioneer women with lines like “my beauty will pass someday, but the land will only grow more beautiful”? What does it prove? That the Western myth is most at home in a setting of innocence, that “Silverado” understands that and that somewhere in our hearts there may still be memories of little boys and girls who chose who got to be the good guys on the long walk home.