“This kind of certainty comes but once in a lifetime.”

— Robert to Francesca

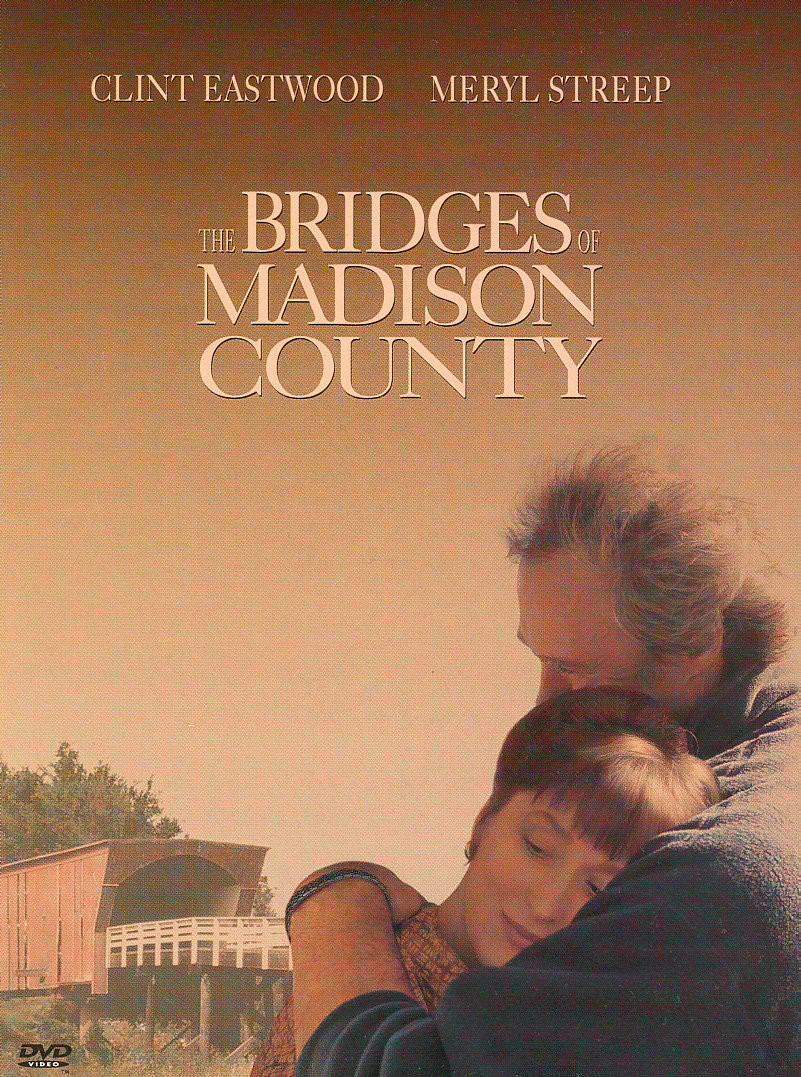

Clint Eastwood’s “The Bridges of Madison County” is not about love and not about sex, but about an idea. The film opens with the information that two people once met and fell in love, but decided not to spend the rest of their lives together. The implication is: If they had acted on their desire, they would not have deserved such a love.

Almost everybody knows the story by now. Robert James Waller’s novel has been a huge best-seller. Its prose is not distinguished, but its story is compelling: He provides the fantasy of total eroticism within perfect virtue, elevating to a spiritual level the common fantasy in which a virile stranger materializes in the kitchen of a quiet housewife and takes her into his arms.

Waller’s gift is to make the housewife feel virtuous afterward.

It is easy to analyze the mechanism, but more difficult to explain why this film is so deeply moving — why Clint Eastwood and Meryl Streep have made it into a wonderful movie love story, playing Robert and Francesca. We know, of course, that they will meet, fall in love and part forever. It is necessary that they part. If the story had ended “happily” with them running away together, no one would have read Waller’s book and no movie would exist. The emotional peak of the movie is the renunciation, when Francesca does not open the door of her husband’s truck and run to Robert. This moment, and not the moment when the characters first kiss, or make love, is the film’s passionate climax.

When Eastwood announced that he had bought the novel and planned to direct and star in the movie, eyebrows were raised.

Readers had already cast it in their minds, and not with Eastwood — or with Meryl Streep, for that matter. There is still a tendency to identify Eastwood with his cowboy and cop roles, and to forget that in recent years he has grown into one of the most creative forces in Hollywood, both as an actor and a director. He was taking a chance by casting himself as Robert Kincaid, but it pays off in a performance that is quiet, gentle and yet very masculine.

And Streep wonderfully embodies Francesca Johnson, the Italian woman who finds herself with a husband and children, living on a farm in the middle of a flat Iowa horizon. The two of them construct their performances not out of grand gestures, but out of countless subtle little moments of growing love; a time comes when they are solemn in the presence of the joy that has come to them.

Kincaid is a photographer for National Geographic, shooting a story on the covered bridges of the county. Francesca’s husband and children have left home for several days to go to the Illinois State Fair. Photographer and housewife meet, and an awkward but friendly conversation leads to an offer of iced tea; then she shyly asks him to stay for dinner.

One of the story’s mysteries is just when each of them becomes erotically aware of the other, and there is a moment, when he goes out to get beer from the car, and she pauses while preparing salad, when she not quite smiles to herself. She seems happy; there is a lift in her heart. In another scene, she answers the telephone and, standing behind him, adjusts his collar, brushes his neck with her finger, and then leaves her hand resting on his shoulder. Very quietly.

Eastwood and his cinematographer, Jack N. Green, find a wonderful play of light, shadow and candlelight in the key scenes across the kitchen table, with jazz and blues playing softly on a radio. They understand that Richard and Francesca are not falling in love with each other, exactly — that takes time, when you are middle-aged — but with the idea of their love, with what Richard calls “certainty.” One of the sources of the movie’s poignancy is that the flowering of the love will be forever deferred; they will know they are right for each other, and not follow up on their knowledge.

Robert wants her to leave with him. The notion is enormously attractive to her. Life on the farm is “not what I dreamed of when I was a girl.” She envies his life of travel. Not understanding quite how tied she is to the land, he suggests her husband could take her “on a safari.” Her smile shows what a wild idea that is. “What’s he like?” Robert asks. “He’s very clean,” she replies. “Hard-working . . . gentle . . . a good father.”

And he is. The story never makes the mistake of portraying Richard Johnson as a bad husband. But we have seen, in an early scene, that there is no conversation around the Johnson family dinner table. With Robert Kincaid, there is much conversation; they talk of their ideals, and she says, “But how can you live for just what you want?” And, quietly, “We are the choices that we have made, Robert.” And they talk on, quoting Yeats, smoking Camels, dancing to the radio.

All of the scenes involving Eastwood and Streep find the right notes and shadings. The surrounding story — involving Francesca’s adult son and daughter finding her diaries and reading her story after her death — is not as successful. I know this framing mechanism, added by writer Richard LaGravenese, is necessary; thewhole emotional tone of the romance depends on it belonging to the lost past. And yet Annie Corley and Victor Slezak, as Caroline and Michael, never seem quite real, and Michael’s shock at his mother’s behavior, in particular, seems forced, like a story device. The payoff at the end — as they reassess their own lives — seems perfunctory.

But the central story glows. I’ve seen the movie twice now and was even more involved the second time, because I was able to pay more attention to the nuances of voice and gesture. Such a story could so easily be vulgarized, could be reduced to obvious elements of seduction, sex and melodramatic parting. Streep and Eastwood weave a spell, and it is based on that particular knowledge of love and self that comes with middle age. Younger characters might have run off together. Older ones might not have dared to declare themselves.

“The Bridges of Madison County” is about two people who find the promise of perfect personal happiness, and understand, with sadness and acceptance, that the most important things in life are not always about making yourself happy.