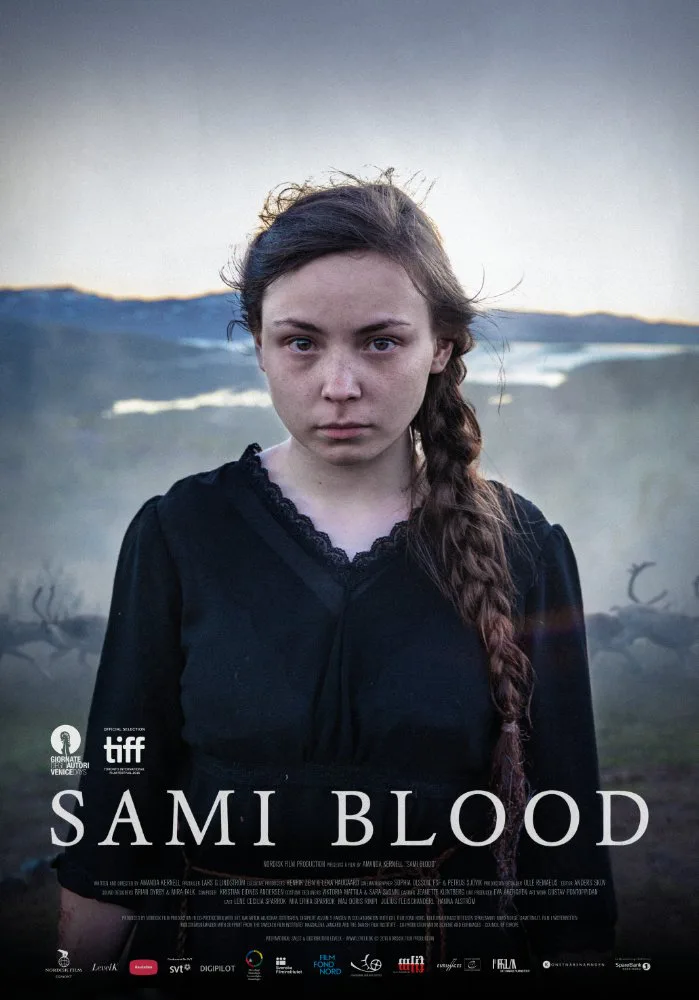

Though its title sound like it could be the name of a heavy-metal band’s lead singer, “Sami Blood” is a Swedish-Norwegian-Danish co-production that concerns the Sami people, an indigenous population that raises reindeer in Scandinavia’s far north and, in the film’s telling, were oppressed and disdained by other Swedes in the 1930s, when most of the story is set.

But the historical and anthropological interest of entering into a little-known culture is only half the film’s appeal. The other half, centered on a precocious Sami girl who wants to leave her rural roots behind, is a lyrical coming-of-age tale of a sort that Scandinavian filmmakers have long had both a fondness and an aptitude for.

Amanda Kernell, the film’s writer/director, is half-Sami so she’s dealing with a culture she’s intimately familiar with. Yet the film’s basic story and situation are ones that will be familiar to anyone from a land where indigenous peoples have been ruled over and deemed inferior by colonizers. Indeed, American viewers are bound to think frequently of the treatment meted out to Native Americans in the years after they were forced to live on reservations.

The film opens in the recent past with an old lady named Christina (Maj Doris Rimpi) being obliged to leave her home in the city and return to Lapland to attend the funeral of her sister. The woman is clearly unhappy about having to make the trip and re-encounter the culture she left many decades before. She tells people she’s from southern Sweden and pretends to speak only Swedish, not Sami.

When the story shifts back to the ‘30s, we meet Christina’s adolescent self, whose name is Elle-Marja (Lene Cecilia Sparrok). Though the girl’s father is dead, she lives comfortably with her mother (Katarina Blind), reindeer herder, and dotes on her younger sister (Mia Erika Sparrok) until the two girls are sent away to a special boarding school for Sami children, where the price of education lies in learning of her people’s inferiority.

Though she’s introduced to poetry by one kindly-seeming, very white-skinned teacher (Hanna Alstrom), Elle-Marja everywhere is given to understand that her racial inferiority means that serious achievement and advanced learning are not expected of her. She merely needs to learn her place. Reflecting the same kind of “scientific” racism that Nazis practiced in the same decade, the girls are even measured and photographed nude in efforts to document and probe their “difference.”

Being headstrong as well as intelligent, Elle-Marja soon manifests an inclination to rebel, which means getting out of Lapland and pursuing real education. One form of impetus arrives at a dance. While most of the local boys deride the Samis as “filthy Lapps,” Elle-Marja meets a very good-looking young man who’s visiting from Uppsala, Niklas (Julius Fleischanderl), and the romantic chemistry is instantaneous.

Taking that attraction as deeper and more substantive than it obviously was, the girl soon shows up at Niklas’ middle-class home in Uppsala and tells his mom that the boy has said she could stay with them. Stumped and uncomfortable, Niklas’ parents allow Elle-Marja to stay one night, and during that time, the two young people become lovers, something that the folks immediately perceive the next day and ask Elle-Marja to leave. She, however, remains determined to start a new life no matter what the obstacles.

The film’s success comes from how Kernell’s skills as a director match the ambitions of her script. The story’s range of moods—from the sweetness of first love to the bitterness of racial shaming—could have made for an uneven or episodic feel to the film, but Kernell’s very nuanced, carefully naturalistic direction provides a unity of tone that skillfully bridges past and present, city and country, as well as diverse emotions.

Kernell proves equally adept in her work with her cast. The blend of professional actors and Sami natives works beautifully, and young Lene Cecilia Sparrok is exceptionally fine as Elle-Marja. The work of director and the actress easily make this one of the year’s most impressive debuts.

One curiosity for this reviewer is that religion plays no role in the story. The omission has been noted in other European films of late. Whatever the reason for it, the decision seems at odds with how such scenarios often played out in real life, just as it removes us from the omnipresent obsession with God in the Sweden of Ingmar Bergman. Of course, there is a hint of religion in the name that Elle-Marja takes as her urban disguise, Christina, and it’s to the film’s credit that it shows that leaving behind her Sami identity hasn’t made her happy; indeed, she seems to have internalized all the insults once visited on her.