You don’t always notice it, but during a lot of the scenes in “Safe” there’s a low-level hum on the soundtrack. This is not an audio flaw but a subtle effect: It suggests that malevolent machinery of some sort is always at work somewhere nearby. Air conditioning, perhaps, or electrical motors, or idling engines, sending gases and waste products into the air. The effect is to make the movie’s environment quietly menacing.

The movie tells the story of Carol (Julianne Moore), who may be allergic to her environment. Something is certainly getting to her. She lives in an affluent, antiseptic, luxurious Southern California home. Her only duties are to care for her health and appearance. She works out at the gym, drinks mineral water, uneasily supervises her household staff and attends “benefit luncheons.” Her husband Greg (Xander Berkeley) is a distant figure, who never quite seems to see her.

One day Carol collapses. There doesn’t seem to be a medical reason for this lapse, and soon she is seeing not a medical doctor but a psychiatrist, who suggests that the problem is within herself.

He isn’t much help. She grows weaker, more frightened. She suffers anxiety attacks. The world seems to be closing in on her. Eventually the movie, if not her husband, concludes that the environment is making her sick. She’s being attacked by plastics, ozone, chemicals, high-energy wires, pollution, additives, preservatives, hamburger gases – the whole laundry list.

Carol escapes from the poisons by going to live at a spa in the desert, with other people who are also in retreat from debilitating allergies. And it is here that the movie gets sneaky, and interesting. The spa (run by a man who lives in a mansion overlooking the more humble quarters of the customers) is a touchy-feely kind of place, where once again Carol’s problems are approached with the assumption that somehow she caused them. The leader, Peter (Peter Friedman), suggests in his selfhelp exhortations that if his patients could only get in touch with themselves, go with the flow, etc., they’d improve.

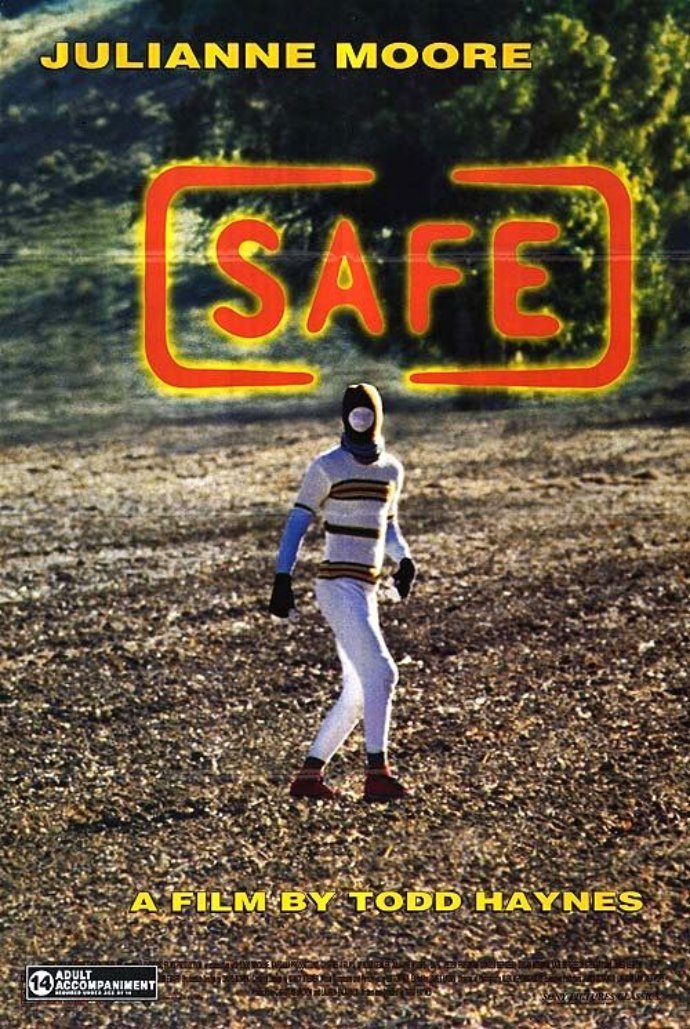

Carol does not get better. Nearby trucks still seem to be spewing out exhausts. She moves into a kind of igloo that is completely sterile. Maybe she’ll be safe there. And as she continues her desperate search, “Safe” reveals itself as a little more complicated than it first seemed.

The set-up scenes have all the hallmarks of a made-for-TV docudrama about the disease of the week. We settle in confidently, able to predict what will happen: Carol’s problems will be diagnosed, the environment will be blamed, and there will be an 800 number at the end where we can call for more information about how to save the planet. But that isn’t how “Safe” develops at all.

Instead, Todd Haynes, the writer and director, has something more insidious up his sleeve. The movie starts out dealing with one problem (environmental poisoning) and ends up attacking another (a blissed-out cult that charges big dollars to suffering people, who pay to hear the leader blame them for their troubles). And then there’s another level. To some degree, “Safe” suggests that Carol may in fact be responsible for aspects of her illness. Her life and world are portrayed as so empty, so pointless, that perhaps she has grown allergic as a form of protest. In that case, the spa won’t help either, because it is simply a new form of the same spoiled lifestyle.

“Safe” never declares itself for any of these possibilities.

That is another of the movie’s intriguing aspects. It centers everything on Carol, who is played by Moore as the kind of woman whom you feel like assisting to a nearby chair. Carol is not very bright.

She’s too dazed by her affluent lifestyle to know what, or if, she thinks about it. Maybe she is poisoning herself. And maybe the blissful group leaders at the spa are doing to her mind what pollution did to her lungs. Or maybe it’s a tripleheader: Maybe the environment is poisoned, and the group is phony, and Carol is gnawing away at her own psychic health. Now there’s a fine mess.