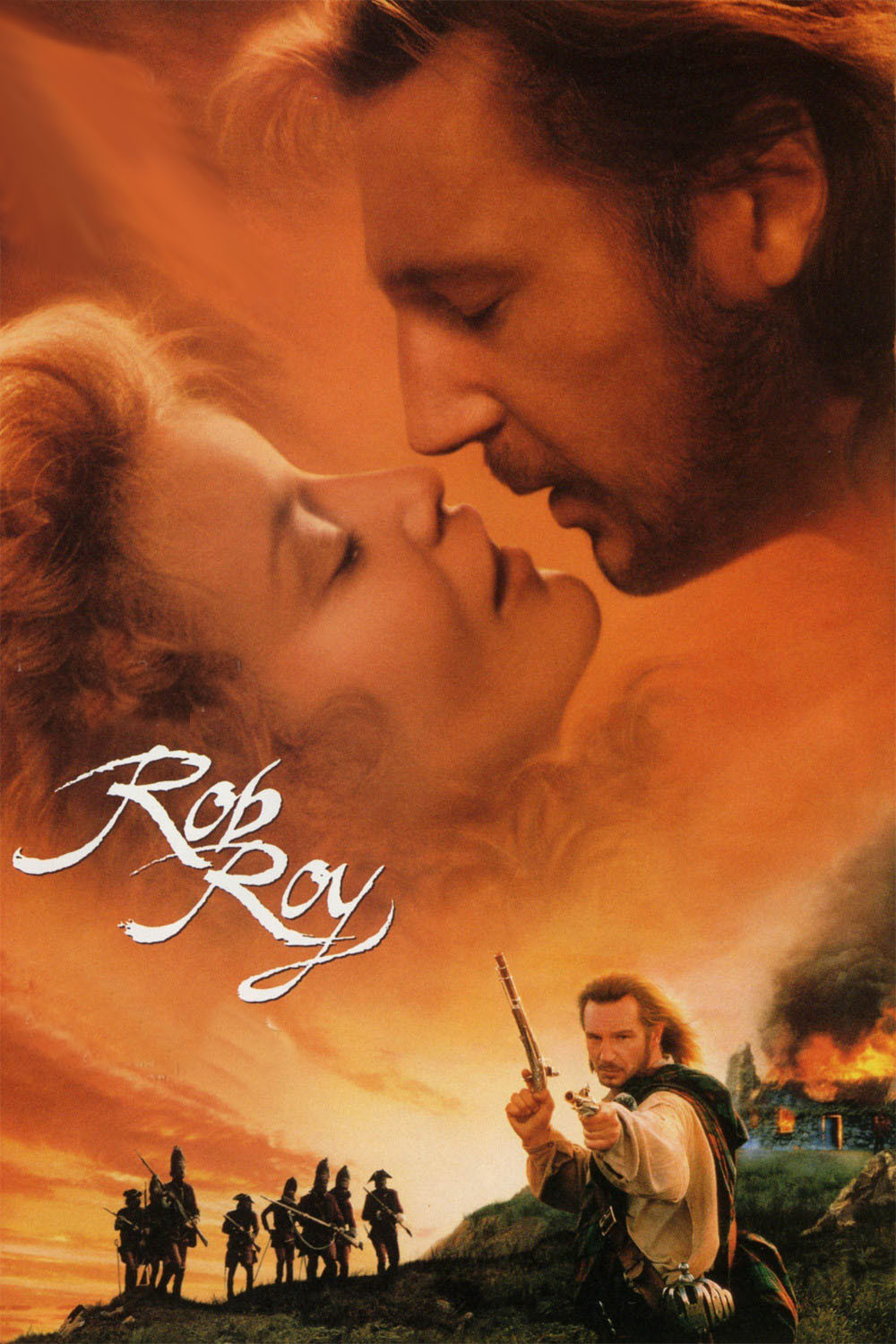

Strange. I thought I had seen enough sword fights in movies to last a lifetime, but I was wrong. The sword fight in “Rob Roy” reinvents the exercise, and the movie itself brings hot red blood to the costume genre. This is a splendid, rousing historical adventure, an example of what can happen when the best direction, acting, writing and technical credits are brought to bear on what might look like shopworn material.

The movie is based on a swashbuckling novel by Sir Walter Scott, a world-class overwriter who in his time was compared to Shakespeare, and in ours to Danielle Steel. I can think of no higher compliment to the movie than that it awakened in me a desire to read Scott’s novel, although when I failed to find it on my shelves, I was able to live with the disappointment.

What’s best about the movie is its vivid picture of the time and place (Scotland, circa 1713), and the kinds of personalities produced by a world where the simple people still believed in romantic chivalry, while the aristocracy embraced decadence and courted intrigue. Rob Roy is a hero not simply because he is tall, good and strong, but because he will sacrifice his life rather than compromise his word. And the film’s villains are magnificent because they are so smart, cunning and smarmy: Not content with merely being despicable, they work at it.

The story takes place at a time when Scots-Catholic Jacobites lived in uneasy proximity with the Protestant English land-owning aristocracy. A farmer and clan leader, Rob Roy MacGregor (Liam Neeson) goes to the local Marquis of Montrose (John Hurt) for a loan of 1,000 pounds. He plans to use to the money to buy and fatten cattle, turn a profit and repay the loan. The Marquis grants the loan.

But the secret of the money is shared by the blubbery Killearn (Brian Cox) with the foppish Archibald Cunningham (Tim Roth), a prancing dandy whose effete exterior conceals a steel-trap mind and deadly swordsmanship. Cunningham, always broke, is in debt to the Marquis and needs money desperately. He waylays Rob Roy’s messenger (Eric Stoltz), kills him, steals the money and leaves MacGregor in default of his home and lands. Rob Roy then of course becomes an outlaw, leading his clan in defiance of the English troops.

This story outline could have produced yet another tired historical epic with yeomen dashing around on horses, quaffing ale and eating burnt sheep with both hands, while their betters practiced the minuet. (“Don’t give me any more pictures where they write with feathers!” Jack Warner once pleaded with his producers.) Instead, in the hands of director Michael Caton-Jones, it produces intense character studies. Liam Neeson, tall and grand, makes an effortless hero as Rob Roy. Jessica Lange, as his wife, Mary, has a fierce strength of character that drives her to defend her home and children, defy her husband when she finds it necessary – and keep within her the secret that she has been raped, because she fears if Rob Roy discovers it, he will lose his life while seeking vengeance.

Great villains make melodrama, and Tim Roth, as Cunningham, is crucial to the success of this film. Resplendent in frilly court costumes, pudding-faced beneath a curly wig, he makes a foppish dandy; no matter how many times you saw “Pulp Fiction,” you will never recognize him as Honey Bunny’s main man. What is intriguing is the way his exterior is really a disguise: In fact, he is one of the deadliest sword fighters in England, and a sexual outlaw with an insatiable appetite, who boasts, “Love is a dunghill, and I am but a cock that climbs upon it to crow.” The conflict in “Rob Roy” is quickly simplified: Cunningham, who stole the money, is assigned by the Marquis to capture Rob Roy, who is blamed for its disappearance. The key question is, whose word will the Marquis believe: that of Rob Roy, a peasant, or Cunningham, an aristocrat? What is intriguing in John Hurt’s performance as the Marquis is the way he nurtures suspicions about Cunningham (“You are in cash, but have no means . . .”) and yet is willing to have Rob Roy die, because it is a matter of saving face.

Another key player in the drama is the other powerful local aristocrat, the Duke of Argyll (Andrew Keir), who seems to support the cause of the deposed Catholic monarchy against the Protestant usurpers. Montrose offers Rob Roy forgiveness of his debt if he will denounce Argyll as a Jacobite, but Rob Roy refuses, and eventually it is Argyll who arranges for the whole matter to be settled in a sword fight between Rob Roy and Cunningham.

The sword fighting sequence, staged by William Hobbs, is the best of its sort ever done. In most movie sword fights, the participants leap about effortlessly, their blades shimmering and clashing. Here we get the sense of the deadly stakes, and the great physical effort involved.

Cunningham chooses a rapier, Rob Roy a broadsword (their weapons reflect their personalities), and the fight is punctuated by passages of dead silence, except for heavy breathing. They become very tired.

They are both wounded. The pauses grow longer, until the duel seems like a chess match in which thought counts for more than action. It is one of the great action sequences in movie history, and “Rob Roy” is a fabulous entertainment.