Brazil is a country of continental dimensions whose filmmaking reflects its sprawling size. In any given year, just look at five or six films produced in different regions of the country and you will find such thematic, aesthetic and linguistic diversity that you’d feel they could well have been made on different planets. There are dumb populist comedies, exercises in style, narrative experiments, dense dramas and historical recreations.

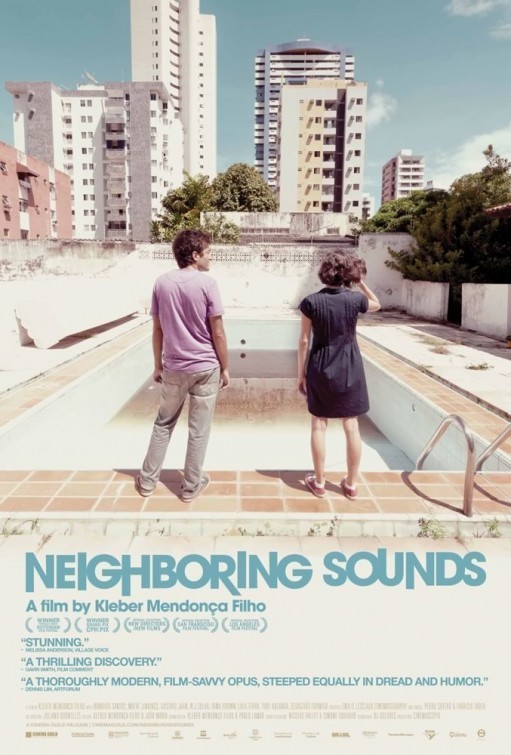

And then there’s “Neighboring Sounds,” the first narrative feature by film critic Kleber Mendonça Filho.

Written by Mendonça and divided into three parts, the film weaves between a dozen characters who live on the same street in Recife (the capital of Pernambuco, in the Northeast of Brazil). They get into petty conflicts with one another, venting grievances that an old communist would call “petit-bourgeois” (and that the Internet generation would label #MiddleClassProblems), while trying to extract as much happiness as they can from an environment that offers minimal inspiration. In this sense, “Neighboring Sounds” presents itself not only as a character study, but also as an authentic socio-economic class study.

Contained in their apartments by ubiquitous iron bars installed to provide security but evoking a prison-like atmosphere, the characters express their humanity and their desire for freedom as circumstances allow: a boy tries to play ball in the street but is continually frustrated, a pair of embracing teenagers kiss in a concrete corner, and anonymous individuals paint messages of love on the asphalt in futile defiance of the oppressive gray concrete. So when the fantastic editing abruptly cuts from a shot of the city’s skyline to one that shows several empty bottles on a table (in a beautifully done graphic match cut), we notice the ironic point of the filmmaker without feeling he’s trying to hammer his message on our heads.

Including selected elements from his excellent short film “Eletrodoméstica” (2005), Mendonça shows particular affection for Bia (Jinkings), a housewife who spends sleepless nights due to the constant barking of the neighbor’s dog and who tries to bring some color to her day by smoking a joint, blowing the smoke into a vacuum cleaner, or masturbating with the help of the washing machine — converting her appliances into survival tools in a maddeningly prosaic and pointless daily life. Evoking Bia’s loneliness through a particularly beautiful shots in which she can be seen sitting in the corner of a frame plunged into darkness, the filmmaker is also able to focus on the punctual harmony of her life — as in the touching and intimate moment in which, lying on the couch, she receives an improvised massage from her children.

Undeterred in its portrayal of the middle class as a group that, even if well-intentioned, seems blind to the economic and social differences in Brazil, the movie can be summed up by the scene that shows a meeting of a building’s residents in which one of them complains about the fact that her magazine is being delivered “unwrapped.” Even after jumping in to defend the poor doorman, another tenant fails to vote to save the old man’s job — choosing instead leave the meeting in order to meet a girl. Later on, that same character will try to prove his understanding of the daily struggle of his maid’s family by commenting on the time he had to work while studying abroad — an attitude that is condescending, obtuse and, even if well-meaning, extremely offensive.

Expertly balancing the narrative between humor and an approach that occasionally borders on the experimental (a trademark of his short films), Mendonça is able to make us laugh by presenting a character who expresses horror upon hearing of a suicide in the building only to ask for a discount on rent. But his film is also capable of plunging us into a state of horror by diving into a dark nightmare in which dozens of menacing figures jump over the walls of the neighborhood — an intriguing representation of the urban paranoia and capitalist guilt of those who live in constant fear that the miserable will finally rebel against economic oppression and burst the dam that keeps them imprisoned. (It’s not an accident that Mendonça also includes a shot of dozens of shacks suffocated amid tall and luxurious buildings.)

Opening the narrative with a series of black-and-white photos that depict aspects of the hard life of rural workers in the past, the film expertly demonstrates that, in a way, the old economic logic is still in place. The street on which the story is set can be seen as an urban update of that reality. We notice, for example, that Francisco (played by W.J. Solha as a man accustomed to being obeyed) not only owns most of the neighborhood’s real estate but also keeps his offspring around him, working and taking care of the family business. Likewise, it is interesting how the old maid’s daughter, unlike her amiable mother, seems aways angry, a sign of the new generation’s growing frustration in the face of the social and economic injustice under which they lived for centuries.

Echoing the melancholic tone of the characters’ interactions, “Neighboring Sounds” benefits from a fantastically detailed sound design which, instead of simply reflecting reality, is employed to suggest ideas, feelings and memories — from the rhythmic beat that follows Francisco’s nighttime walk to the growingly louder and tense noise in the elevator during the climax. Moreover, Mendonça is courageous enough as an artist to escape from the realism he adopts for most of the film by venturing, in the third act, into a realm that borders on fantasy — as in the moment he shows us the nostalgic vision of a man who suddenly sees the street from the perspective of his childhood. In a similar manner, the filmmaker shocks us with an almost subliminal waterfall of blood that suggests a world of suppressed anger and frustration inside the main character. And if nothing else, the sequence in which João and Sofia (the lovely Irma Brown) visit his grandfather is a tribute to cinema itself, transforming an old theater, now taken over by weeds and mold, into a living memory of the past through sound.

Establishing itself as a movie about the desires, anxieties and aspirations of a social class that seems uncertain of its role in the world, “Neighboring Sounds” is also a film about the loss of our roots or, at least, the sad destruction of our history. “The house in which you lived will be demolished,” says John to his girlfriend — a literal piece of information that also works as a metaphor. And so, when the girl visits the place where she spent part of her youth and goes into her old bedroom, we feel the impending loss of a room that, even if extremely common, assumes the contours of a private museum.

When she realizes that the paper constellation she glued in the ceiling remains there and asks her boyfriend to lift her, the gesture emerges as a masterful symbol of someone trying to touch, for the last time, the stars of her childhood’s sky before they are torn away by the cruel and inexorable passage of time.

Pablo Villaça is a writer, filmmaker and a film critic since 1994. He’s the creator of Cinema em Cena, Brazil’s oldest movie website, and one of Roger Ebert’s Far-Flung Correspondents since 2011.