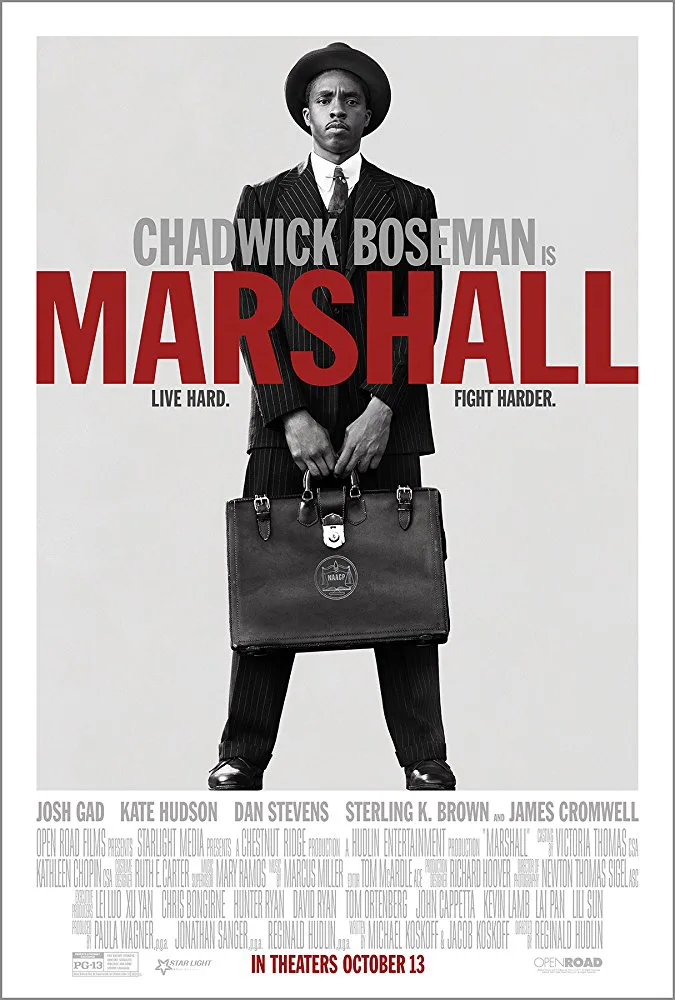

We are republishing this piece on the homepage in allegiance with a critical American movement that upholds Black voices. For a growing resource list with information on where you can donate, connect with activists, learn more about the protests, and find anti-racism reading, click here. “Marshall” is currently streaming on Amazon. #BlackLivesMatter.

The 1940s legal thriller “Marshall” is a solid drama that gives viewers a glimpse into an alternate universe—one where African-American actors could be treated as old school movie stars, in period pieces that are less concerned with giving audiences a solemn, Oscar-baiting history lesson than an entertaining story that happens to be drawn from life.

Chadwick Boseman, Hollywood’s go-to guy for playing important Black Americans, adds another icon to his gallery: NAACP attorney and future Supreme Court justice Thurgood Marshall, a New Yorker dispatched to Bridgeport, Connecticut, to defend a black man, Joseph Spell (Sterling K. Brown), who stands accused of the rape and attempted murder of a white society woman, Eleanor Strubing (Kate Hudson). Filmmaker Reginald Hudlin (“House Party,” “Boomerang”) adapts a script by the father-son screenwriting team of Michael and Jacob Koskoff that jumps off from a real case. Many of the most seemingly outrageous twists are pulled from the record.

One is a decision by the sitting judge (James Cromwell), an imperious old white man who doesn’t appreciate having a cocky black New Yorker in his court, to turn Marshall into a mute bystander by declaring that only attorneys licensed to practice law in Connecticut can argue before his bench. This feels like an early checkmate intended to send Spell straight to prison: the NAACP only assigned Marshall to Bridgeport in the first place because the white majority had already made up its mind about Spell’s guilt and no local lawyers would take his case.

And so the hero is forced to use his co-counsel, Sam Friedman (Josh Gad), an insurance lawyer who’s never tried a criminal case before, as a sock puppet. He works out details of their strategy behind the scenes, then guides Friedman during jury selection and opening arguments via handwritten notes, facial reactions, and irritated sighs and grunts. From here, “Marshall” turns into a mismatched buddy film, of a kind that we’ve never seen before.

Although Boseman is 100% credible as a brilliant attorney, especially when Marshall and Friedman are trying to work around the judge’s restrictions, his performance as Marshall is not an imitation; nor is it overly concerned with giving us a true psychological portrait of Thurgood Marshall the man. It’s more of a classic Hollywood alpha male badass performance, in the vein of Humphrey Bogart, Paul Newman, and other 20th century white superstars who reveled in playing sarcastic, sexy, domineering jerks, but were so exciting to watch—whether orating, listening, smoking a cigarette in a jazz club, or just wearing an impeccably tailored suit and walking from point A to point B—that you enjoyed them no matter what their characters did. This Thurgood Marshall is so accomplished at such a young age—having already argued his first U.S. Supreme Court case, and claimed Langston Hughes (Jussie Smollett) and Zora Neale Hurston (Chilli) as drinking buddies—that when he arrives in Bridgeport he offhandedly orders Friedman to help him with his bags, then pokes fun at him and plays head-games with him every chance he gets. (Apparently the latter is an actual Thurgood Marshall trait: he was suspended twice from Pennsylvania’s Lincoln University for pranks and hazing.) He’s a bit of a bastard at times.

But just when you start to worry that “Marshall” is about to settle into a repetitious groove, with a know-it-all hero solving a nebbish’s problems, the full force of the town’s majority starts to weigh on the duo, freighting their work with paranoia and fear of violence. What follows is a humbling experience for both men. “Marshall” is not a soup-to-nuts biography of one of the most significant figures in U.S. legal history, but a legal potboiler dependent on teamwork. It pays attention to issues of racial, religious and gender discrimination without wavering from its main objective: giving us an entertaining film about a couple of guys who are in way over their heads.

One of the movie’s most intriguing qualities is the way that it shows how power and respect vary depending on what room you’re in, and who’s in it with you. Marshall moseys into Bridgeport as if he’s wearing an invisible cape, but in court, in the city jail, at home with his wife Buster (Keesha Sharp), and in Harlem nightspots with cultural giants, he is diminished, by his own choice or against his will; we perceive him differently, and he perceives himself differently. When Marshall is face-to-face with brawny white men who hate him on sight, the movie sharply reminds us that there are situations where college degrees aren’t worth the paper they’re printed on. A less frightening but equally dispiriting scene finds Marshall speaking to a black lawyer in Bridgeport who passed the bar but was denied a license to practice law because of his race.

Friedman, too, seems like a different person depending on what room he’s in. Marshall’s swagger and awesome legal track record intimidate him, but his own younger brother and law partner idolizes and defers to him, and it’s obvious that in Bridgeport’s Jewish community he’s a man of influence, respected in large part because he has the nerve to accept challenges that others run from. There’s a marvelous moment in a synagogue men’s room where a member of the congregation seems as if he’s about to insult Friedman for representing an accused “schwarze” rapist, then slips some cash into Friedman’s jacket pocket.

Both Boseman and Gad do a superb job of ratcheting their characters’ physical confidence up and down by degrees, depending on the circumstances. This gives the movie a richer sense of time and place than you might have expected. It also draws parallels between the experience of Jews and blacks in 1940s America that come to fruition in the movie’s final summation.

Hudlin and his writers pander a bit at times. Too many important moments are spelled out in dialogue even though images and performances have already explained what’s at stake; some of the twists are too predictable, and in the last third, especially, you may start to suspect that the film is playing fast and loose with the historical record to create a more superficially exciting story. (Although I knew Thurgood Marshall could write a dissenting opinion for the ages, his street-fighting skill was news to me.)

But the movie’s missteps and over-reaches are all of a piece. The farther away from the courtroom we get, the more “Marshall” starts to feel like a detective thriller with subtle Western movie accents: the terse, one-word title positions its hero as a tough, smart sheriff trying to clean up a corrupt town. There’s an almost B-movie quality to certain parts—a touch of “Shaft”—and I mean that as praise. What I like most about Marshall the man and “Marshall” the film are their laid back confidence. It carries itself as if we’ve already seen a lot of projects like this one—as if there’s a new funny, exciting period piece about a brilliant, two-fisted black lawyer in theaters every week, and this is just the latest. I hope the filmmakers are already working on “Marshall Returns.”

“Marshall” is currently streaming on Amazon.