She is born into a time of tranquillity, in which the people of her village live as they have for many centuries. All is ordered; everyone has his place, including the ancestors who are buried on land that has been in the same family since time immemorial. Then a warplane streaks across the sky, and in an instant all she knows is destroyed. Her name is Le Ly, and her destiny will take her from the rice fields of the Central Highlands to the suburban split-levels of California.

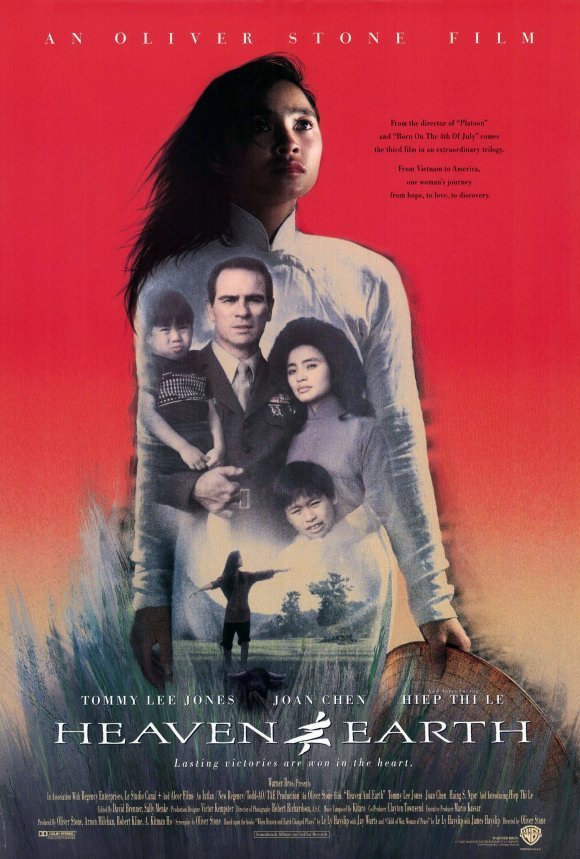

Oliver Stone has made films about Vietnam from the point of view of a combat infantryman and a disabled veteran, and now in “Heaven and Earth” he completes his trilogy by viewing the war through the eyes of a Vietnamese woman. The story is factual, as were Stone’s “Platoon” (1986), inspired by his own combat in Vietnam, and “Born on the Fourth of July” (1989), based on the autobiography of Ron Kovic.

“Heaven and Earth” is based on two books by Le Ly Hayslip, who is now a successful Vietnamese-American businesswoman in California.

Stone is not known for his films about women. From “Salvador” through “Talk Radio,” “Wall Street,” “The Doors” and “JFK,” he has made films about men to whom women were a pleasant but not central element of life. This is the first time he has tried to place himself inside a woman’s imagination, and that he succeeds so well is due partly, I think, to an extraordinary performance by Hiep Thi Le in the leading role. She was born in Vietnam, came to America as a child, knows both worlds, and is able to reflect the disorientation of a woman whose life and values are placed in turmoil.

Seeing the war through her eyes, watching as foreign troops march across the fields of her family, we are asked by Stone to see how fundamentally wrongheaded the American strategy in Vietnam was.

The overarching goal was to win the “hearts and minds” of the Vietnamese people. To this end, we uprooted them from the land of their ancestors, and herded them into “strategic hamlets” designed to keep the Viet Cong out, although they functioned more like enclosures to keep the occupants in. This experience actually encouraged them to identify with the Cong, who understood the same values.

For ordinary farmers who wanted only to tend their crops, the war brought horrible choices. We watch as Le Ly’s village is visited both by Viet Cong propagandists and American and South Vietnamese advisers. We see her savagely mistreated by men from both sides, who effortlessly translate their patriotic zeal into the act of rape. We see her separated from her family, joining aimless columns of refugees, and finding herself in Saigon in economy where the Americans had all the money – and what a lot of them were buying were sex and drugs.

Into her life one day comes a tall, craggy American named Steve Butler (Tommy Lee Jones), who does not want her as a prostitute, but as a bride. He is gentle, understanding, persistent, although perhaps if she had been less desperate she would have been able to distinguish a disturbing note when he vowed, “I want an Oriental wife.” His image of her is hopelessly entangled with his own guilt and fear, his inner demons, his need for a woman who will simultaneously forgive him, and surrender to him.

Le Ly returns to America as Mrs. Steve Butler, to a land where the supermarket shelves seem to reach endlessly in every direction and the in-laws regard her as something between a scandal and a pet.

(One of her American relatives is played, in a bit of wicked casting, by Debbie Reynolds.) Le Ly has trouble adjusting, but not as much trouble as her husband, who finds that his training and 20 years as a “military adviser” have left him hopelessly unsuited to civilian life. In these scenes, Jones draws on an earlier character, the Vietnam veteran he played in Lynne Littman’s underrated “Rolling Thunder” (1977). He shows his gift for creating characters who are never more frightening than when they are being nice.

In a time when few American directors are drawn toward political controversy, Stone seeks it out. He loves big subjects and approaches them fearlessly. The Vietnam War is the most important event in recent American history, but only Stone has made it his business as a filmmaker.

Movies are not the best way to make a reasoned argument. For that you need the written word, which can be pinned down, footnoted, double-checked and debated. Movies traffic in emotions. They are about the ways things look and feel. In “Platoon,” “Born on the Fourth of July” and now “Heaven and Earth,” Stone has tried to let us look through eyes that saw three elements of the war.

The first film was about a patriotic young American who went to fight it. The second saw the confused and demoralized aftermath of the war through the eyes of a paralyzed veteran whose country wished to forget him. Now comes a woman who represents all of the ordinary people who wanted only to get on with their ordinary lives.

It is no secret that Stone thinks the Vietnam War was a tragedy for everyone concerned. But he doesn’t make the Viet Cong into the good guys here; they are brutal, arbitrary, sadistic. Americans also commit atrocities (we see possible informers being forced to watch their friends being dropped out of helicopters). The conclusion seems to be that Vietnam was a particularly unwholesome and misguided war, one which those who did not come from the land were inevitably destined to lose.

But Le Ly is also, of course, an outsider when her husband brings her to America. There is one area where I wish Stone had given us more information, and that involves her later life in the United States. She has stayed here, written two books, and prospered. We see the beginnings of that process, as she borrows money from fellow Vietnamese to start a deli. To lose everything, to come to a strange land and make herself a success was her victory, in her war.