For weeks now, we’ve been reading in the papers about public apologies by governments of the Eastern bloc. The Russians admit they were wrong to invade Afghanistan and Czechoslovakia. The East Germans tear down the Berlin Wall and denounce the secret luxuries of their leaders. The Poles and Hungarians say Marxism doesn’t work very well.

There is a temptation for an American, reading these articles, to feel smug. And yet – hold on a minute, here. We had our own disastrous foreign policy mistake, the war in Vietnam. When is President Bush going to get up before Congress and read an apology to the Vietnamese? Never, is the obvious answer. We hail the Soviet bloc for its honesty but see no lessons for ourselves. And yet we have been issuing our own apologies, of a sort. A film like Oliver Stone’s “Born on the Fourth of July” is an apology for Vietnam, uttered by Stone, who fought there, and Ron Kovic, who was paralyzed from the chest down in Vietnam.

Both of them were gung-ho patriots who were eager to answer their country’s call to arms. When they came back home, they were still patriots, hurt and offended by the hostility they experienced from the anti-war movement.

Eventually, both men turned against the war, Kovic most dramatically. He and his wheelchair were thrown out of the 1972 Republican convention, but in 1976 he addressed the Democratic convention. And if you wanted to, you could say his 1976 speech was the equivalent of one of those recent breast-beatings in the Supreme Soviet. We do apologize for our mistakes in this country, but we let our artists do it instead of our politicians.

Kovic came back from the war with a shattered body, but it took a couple of years for the damage to spread to his mind and spirit. By the time he hit bottom he was a demoralized, spiteful man who sought escape in booze and drugs and Mexican whorehouses. Then he began to look outside of himself for a larger pattern to his life, the pattern that inspired his best-selling autobiography, Born on the Fourth of July.

Writer-director Stone, who based his earlier film “Platoon” on his own war experiences, has been trying to film the Kovic story for years. Various stars and studios were attached to the project, but it kept being canceled.

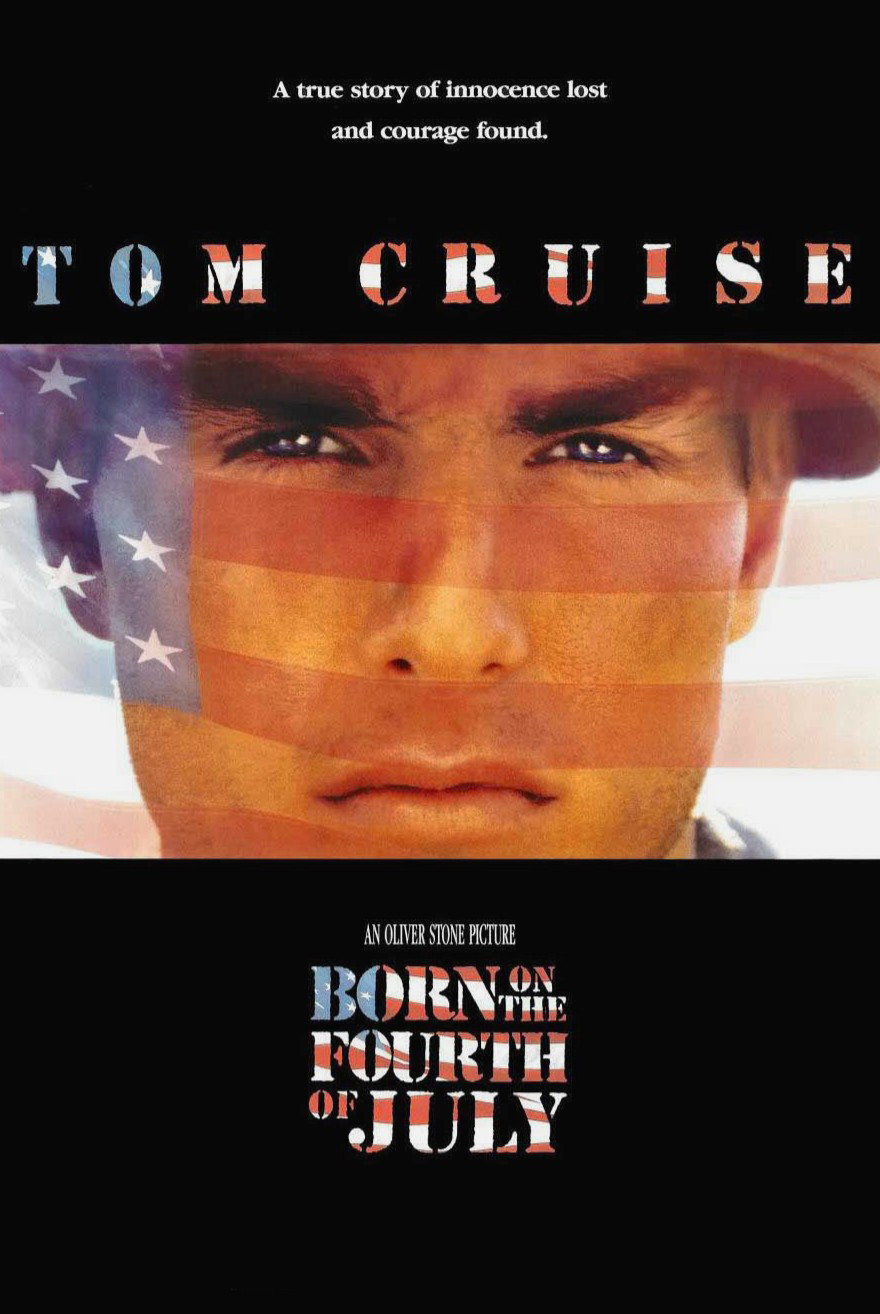

And perhaps that’s just as well, because by waiting this long Stone was able to use Tom Cruise in the leading role. Nothing Cruise has done will prepare you for what he does in “Born on the Fourth of July.” He has been hailed for years now as a great young American actor, but only his first hit film, “Risky Business,” found a perfect match between actor and role. “Top Gun” overwhelmed him with a special-effects display. “The Color Of Money” didn’t explain his behavior in crucial final scenes. “Cocktail” was a cynical attempt to exploit his attractive image. Even in “Rain Man,” he seemed to be holding something in reserve, standing back from his own presence.

In “Born on the Fourth of July,” his performance is so good that the movie lives through it. Stone is able to make his statement with Cruise’s face and voice and doesn’t need to put everything into the dialogue.

The movie begins in the early 1960s with footage of John F. Kennedy on the television exhorting, “Ask not what your country can do for you, ask what you can do for your country.” Young Ron Kovic, star athlete and high school hero, was the kind of kid waiting to hear that message. And when the Marine recruiters came to visit his high school, he was ready to sign up. There was no doubt in his mind: There was a war in Vietnam, and his only worry was that he would miss the action.

He knew there was a danger of being wounded or killed, but, hell, he wanted to make a sacrifice for his country.

His is the kind of spirit all nations must have, from time to time. The problem with the Vietnam War is that it did not deserve it.

There was no way for a patriotic small-town kid to know that, however, and so we follow young Kovic from his last prom to the battlefield. In these scenes, Cruise still looks like Cruise – boyish, open-faced – and I found myself wondering if he would be able to make the transition into the horror that I knew was coming. He was.

Stone was in combat for a year. In “Platoon,” he showed us firefights so confused that we (and the characters) often had little idea where the enemy was. In “Born on the Fourth of July,” Stone directs a crucial battle scene with great clarity so that we can see how Kovic made a mistake. That mistake, which tortures him for years afterward, probably produced the loss of focus that led to his crippling injury.

The scenes that follow, in a military hospital, are merciless in their honesty. If you have even once, for a few hours perhaps, been helpless in a sickbed and unable to summon aid, all of your impotent rage will come flooding back as the movie shows a military care system that is hopelessly overburdened. At one point, Kovic screams out for a suction pump that will drain a wound that might cost him his leg. He will never have feeling in the leg, but, God damn it, he wants to keep it all the same. It’s his. And a distracted doctor absent-mindedly explains about equipment shortages and “budget cutbacks” in care for the wounded vets.

Back in civilian life, Kovic is the hero of a Fourth of July parade, but there are peaceniks on the sidewalks, some of them giving him the finger. He feels more rage. But then his emotional tide turns one night in the backyard of his parents’ home, when he gets drunk with a fellow veteran, and he finds they can talk about things nobody else really understands. It is from this scene that the full power of the Cruise performance develops.

Kovic’s life becomes a series of confusions: bar brawls, self-pity and angry confrontations with women he will never be able to make love with in the ordinary way. His parents love him but are frightened by his rage. Eventually it is suggested that he leave home.

In a scene of Dantean evil, Stone shows Kovic in Mexico with other crippled veterans, paying for women and drugs to take away the pain, and finally, shockingly, abandoned in the desert with another veteran with no way to get back to their wheelchairs or to town. It’s the sort of thing that happens to people who make themselves unbearable to other people who don’t give a damn about them. (In a nod toward “Platoon,” the other crippled veteran in the desert is played by Willem Dafoe, co-star of that film; the other co-star, Tom Berenger, is the Marine who gives the recruitment speech in the opening scenes.) “Born on the Fourth of July,” one of the best movies of the year, is one of those films that steps correctly in the opening moments and then never steps wrongly. It is easy to think of a thousand traps that Stone, Kovic and Cruise could have fallen into, but they fall into none of them.

Although this film has vast amounts of pain and bloodshed and suffering in it, and is at home on battlefields and in hospital wards, it proceeds from a philosophical core: It is not a movie about battle or wounds or recovery, but a movie about an American who changes his mind about the war. The filmmakers realize that is the heart of their story and are faithful to it, even though they could have spun off in countless other directions. This is a film about ideology, played out in the personal experiences of a young man who paid dearly for what he learned. Maybe instead of anybody getting up in Congress and apologizing for the Vietnam War, they could simply hold a screening of this movie on Capitol Hill and call it a day.