How much is enough? The kid keeps asking the millionaire raider and trader. How much money do you want? How much would you be satisfied with? The trader seems to be thinking hard, but the answer is, he just doesn’t know. He’s not even sure how to think about the question. He spends all day trying to make as much money as he possibly can, and he cheerfully bends and breaks the law to make even more millions, but somehow the concept of “enough” eludes him. Like all gamblers, he is perhaps not even really interested in money, but in the action. Money is just the way to keep score.

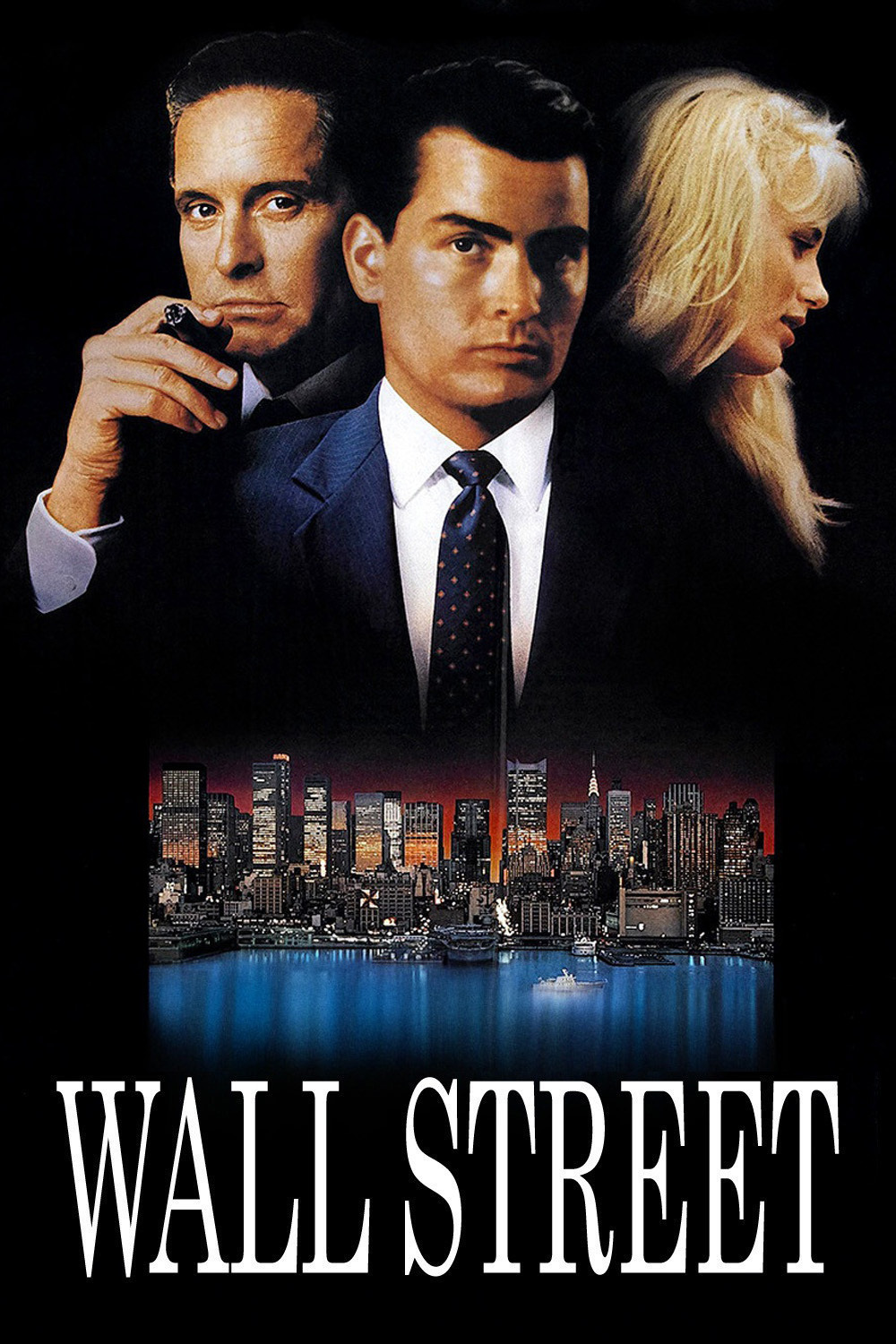

The millionaire is a predator, a corporate raider, a Wall Street shark. His name is Gordon Gekko, the name no doubt inspired by the lizard that feeds on insects and sheds its tail when trapped. Played by Michael Douglas in Oliver Stone’s “Wall Street,” he paces relentlessly behind the desk in his skyscraper office, lighting cigarettes, stabbing them out, checking stock prices on a bank of computers, barking buy and sell orders into a speaker phone. In his personal life he has everything he could possibly want – wife, family, estate, pool, limousine, priceless art objects – and they are all just additional entries on the scoreboard. He likes to win.

The kid is a broker for a second-tier Wall Street firm. He works the phones, soliciting new clients, offering second-hand advice, buying and selling and dreaming. “Just once I’d like to be on that side,” he says, fiercely looking at the telephone a client has just used to stick him with a $7,000 loss. Gekko is his hero. He wants to sell him stock, get into his circle, be like he is. Every day for 39 days, he calls Gekko’s office for an appointment. On the 40th day, Gekko’s birthday, he appears with a box of Havana cigars from Davidoff’s in London, and Gekko grants him an audience.

Maybe Gekko sees something he recognizes. The kid, named Bud Fox (Charlie Sheen), comes from a working-class family. His father (Martin Sheen) is an aircraft mechanic and union leader. Gekko went to a cheap university himself. Desperate to impress Gekko, young Fox passes along some inside information he got from his father. Gekko makes some money on the deal and opens an account with Fox. He also asks him to obtain more insider information, and to spy on a competitor. Fox protests that he is being asked to do something illegal. Perhaps “protests” is too strong a word; he “observes.”

Gekko knows his man. Fox is so hungry to make a killing, he will do anything. Gekko promises him perks – big perks – and they arrive on schedule. One of them is a tall, blond interior designer (Daryl Hannah), who decorates Fox’s expensive new high-rise apartment. The movie’s stylistic approach is rigorous: We are never allowed to luxuriate in the splendor of these new surroundings. The apartment is never quite seen, never relaxed in. When the girl comes to share Fox’s bed, they are seen momentarily, in silhouette. Sex and possessions are secondary to trading, to the action. Ask any gambler.

Stone’s “Wall Street” is a radical critique of the capitalist trading mentality, and it obviously comes at a time when the financial community is especially vulnerable. The movie argues that most small investors are dupes, and that the big market killings are made by men such as Gekko, who swoop in and snap whole companies out from under the noses of their stockholders. What the Gekkos do is immoral and illegal, but they use a little litany to excuse themselves: “Nobody gets hurt.” “Everybody’s doing it.” “There’s something in this deal for everybody.” “Who knows except us?”

The movie has a traditional plot structure: The hungry kid is impressed by the successful older man, seduced by him, betrayed by him, and then tries to turn the tables. The actual details of the plot are not so important as the changes we see in the characters. Few men in recent movies have been colder and more ruthless than Gekko, or more convincing. Fox is, by comparison, a babe in the woods. I would have preferred a young actor who seemed more rapacious, such as James Spader, who has a supporting role in the movie. If the film has a flaw, it is that Sheen never seems quite relentless enough to move in Gekko’s circle.

Stone’s most impressive achievement in this film is to allow all the financial wheeling and dealing to seem complicated and convincing, and yet always have it make sense. The movie can be followed by anybody, because the details of stock manipulation are all filtered through transparent layers of greed. Most of the time we know what’s going on. All of the time, we know why.

Although Gekko’s law-breaking would of course be opposed by most people on Wall Street, his larger value system would be applauded. The trick is to make his kind of money without breaking the law. Financiers who can do that, such as Donald Trump, are mentioned as possible presidential candidates, and in his autobiography Trump states, quite simply, that money no longer interests him very much. He is more motivated by the challenge of a deal and by the desire to win. His frankness is refreshing, but the key to reading that statement is to see that it considers only money, on the one hand, and winning, on the other. No mention is made about creating goods and services, to manufacturing things, to investing in a physical plant, to contributing to the infrastructure.

What’s intriguing about “Wall Street” – what may cause the most discussion in the weeks to come – is that the movie’s real target isn’t Wall Street criminals who break the law. Stone’s target is the value system that places profits and wealth and the Deal above any other consideration. His film is an attack on an atmosphere of financial competitiveness so ferocious that ethics are simply irrelevant, and the laws are sort of like the referee in pro wrestling – part of the show.