When John Huston came back from the war and Humphrey Bogart was a star big enough to choose his next project, the two of them chose to make a film about a seedy loser driven mad by greed. “Wait till you see me in my next picture,” Bogart shouted to a movie critic outside a New York nightclub. “I play the worst s— you ever saw.” The movie was desolate and despairing, the nicest character in it dies trying to defend men who were about to kill him, and the ending is not merely unhappy but like a cosmic joke against the hero’s dreams. Jack L. Warner, the studio boss who sent the crew to Mexican locations and yanked them back when the budget ran out of control, thought it was “definitely the greatest motion picture we have ever made.”

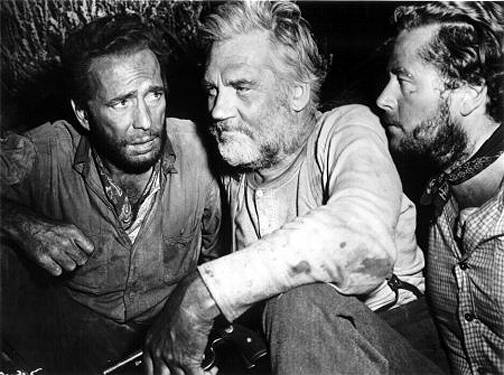

“The Treasure of the Sierra Madre” (1948) is a story in the Joseph Conrad tradition, using adventure not as an end in itself but as a test of its characters. It involves moral disagreements between a wise old man and a paranoid middle-aged man, with a young man forced to choose sides. It tells this story with gusto and Huston’s love of male camaraderie, and it occasionally breaks into laughter — some funny, some bitterly ironic. It happens on a sun-blasted high chaparral landscape, usually desolate, except for the three gold prospectors, although gangs of bandits and villages of Indians materialize when required. At the end, it has Bogart in a delirious mad scene that falls somewhere between “King Lear” and “Greed.”

Bogart plays Fred C. Dobbs, one of the movie characters everybody can name. In 1925 in Tampico, he meets another drifter from America, Bob Curtin (Tim Holt). Both have been cheated out of hard-earned wages by a dishonest employer named McCormick, and when they corner him in a bar, they beat him so savagely that it seems pointless to hang around town. Their next move is suggested by the old-timer Howard (Walter Huston), who they’ve overheard talking about gold. They think he’s good for advice and not much more, but he has the stamina of a goat and is soon filling their ears with practical advice about how to find gold, which is not too hard, and how to keep it and not get killed, which is not too easy.

The heart of the movie takes place on the slopes of mountains, which the title identifies but the characters never do; they simply address it as “mountain.” They are so exposed in this landscape that only Howard’s experience and rough Spanish get them through. They start out as partners, but the moment they find real gold, Dobbs grows avaricious, suggesting they divide their gains three ways, every night. Soon they’re hiding their gold separately, and there is a long night when Dobbs awakens in the tent to find Howard gone, and then Curtin awakens to find Dobbs gone, and finally old Howard observes the turn has come back around to him and so why don’t they get some sleep because they have work to do in the morning.

Howard has been here before (“I know what gold can do to men’s souls’). He plays a tactful peacemaker, agreeing with Dobbs’ paranoid suggestions because he knows they will make little difference at the end of the day: Either they’ll get out with their gold, or they won’t. The performance is a masterpiece by Walter Huston, John’s father, and won an Academy Award (John Huston won two more, for direction and screenplay). Listen to the way the senior Huston talks, rapid-fire, without pause, as if he’s briefing them on an old tale and doesn’t have time to waste on nuance. He does a famous dance when he finally finds gold, playing the stereotype of a grizzled prospector, but see how his eyes are sometimes quiet even when he’s playing the fool; he reads every situation, knows his options, tries to slow Dobbs’ meltdown.

Bogart shows not a shred of star ego in the role, but then he didn’t become a star by being a pretty face. His wife Lauren Bacall writes in her memoirs that Bogart began to experience rapid hair loss on “Dark Passage” (1947), and was completely bald when he arrived at the “Treasure” locations. Doctors blamed his drinking and a B-vitamin deficiency; B-12 shots helped his hair return, but in “Treasure,” all three men wear wigs that were carefully muddied and matted every morning to reflect that day’s difficulties.

Bogart’s break in pictures came in John Huston’s own first film, “The Maltese Falcon” (1941), after the much bigger Warner Bros. star, George Raft, turned it down. Not tall, balding, with a scar on his lip, Bogart could play a hero but loved to be the scrappy little guy; remember his Charlie Allnut in Huston’s “The African Queen” (1951). In “The Treasure of the Sierra Madre,” he plays a character who diminishes steadily as the story moves along, finally disappearing into himself and his delusions. Although Howard saves Dobbs’ life just by being a seasoned mountain man, and Curtin pulls him unconscious from a collapsed mine, he doesn’t trust either one and finds he is capable of killing either one just to get a bigger share of the gold.

He thinks he has killed Curtin, and the moment he does, he tips over into madness. But the harsh logic of the situation has earlier shown that murder is always a choice in these mountains. There is a poignant episode involving the soft-spoken American Jim Cody (Bruce Bennett), who tracks them down to their camp, offers his help, wants a share and analyzes the situation for them: They can either make him a partner or kill him. The scene where the three men take a vote shows clearly how their moral weight balances out.

The movie is based on a novel by the elusive, legendary B. Traven, whose work shows men cornered by the shrinking options offered by nature and danger. Traven was famous for being unknown; the name was a pseudonym, the author was never seen, and indeed the Hollywood agent Paul Kohner, who represented both of the Hustons, acted as Traven’s literary agent without ever meeting him — or did he? Both Huston and Kohner told me in the 1970s that an unprepossessing little man turned up on the Mexican locations and described himself as Traven’s representative. This was, they decided, clearly Traven himself, but they went along with the fiction.

I’ve seen “The Treasure of the Sierra Madre” many times, but watching it again today on a new DVD, I found myself gripped as always by Bogart’s closing scenes. The movie has never really been about gold but about character, and Bogart fearlessly makes Fred C. Dobbs into a pathetic, frightened, selfish man — so sick we would be tempted to pity him, if he were not so undeserving of pity. The other two characters get more or less what they deserve at the end of the film, but with less satisfaction for the audience. After Howard is taken in by an Indian tribe, there is a gratuitous shot, where a young maiden pats his whiskers and he all but winks directly at the camera; this shot, and the idyllic village life surrounding it, belong in a lesser movie.

As the stories of Howard and Curtin evaporate into convention, however, Fred C. Dobbs somehow moves to a higher level of tragedy. Hearing things in the night, desperate for a drink of water, staggering under the desert sun with the gold he valued so much, Dobbs is the tragic hero brought down precisely by his flaws. There is a pitiless stark realism in these scenes that brings the movie to honesty and truth. Leading up to them is a down-market Shakespearean soliloquy when Dobbs thinks he is a murderer and says, “Conscience. What a thing! If you believe you got a conscience, it’ll pester you to death. But if you don’t believe you got one, what could it do to ya?” He finds out.

Note:Bogart starred in two movies where nobody actually said their most most-repeated lines. Nobody says “Play it again, Sam” in “Casablanca,” and in “The Treasure of the Sierra Madre,” Alfonso Bedoya, as the bandit leader, never actually says, “Badges? We don’t need no stinking badges!” He says, “We don’t need no badges. I don’t have to show you any stinking badges.”