The shabby real estate office in “Glengarry Glen Ross” seems likely to become one of the movie places we will remember, like the war room in “Dr. Strangelove” or Hannibal Lecter’s cell. It is divided into two parts: a glassed-in area where the office manager lives, along with his precious “leads” – cards with the names of people who might want to buy real estate – and the rest of the office, given over to the desks of the salesmen, who try to sound rich and confident over the phone, but whose eyes are haunted with despair.

Hour after hour, they make calls to sell real estate that no one wants to buy. They are making no money. It is worse than that.

They are about to lose their jobs. Blake (Alec Baldwin), the slick hotshot from downtown, arrives to give them a chalk-talk and a warning. There is a new sales contest. First prize is a Cadillac.

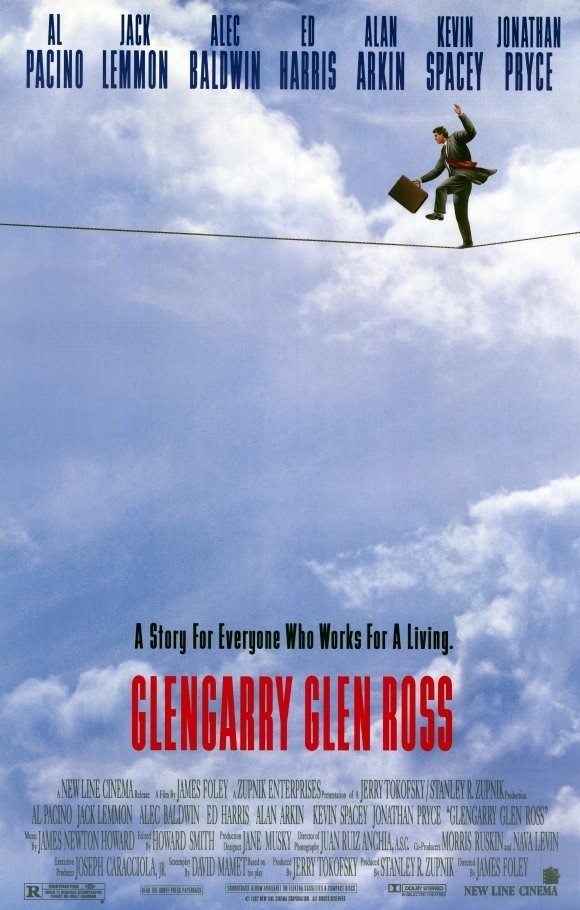

Second prize, a set of steak knives. Third prize is, you’re fired: “Hit the bricks, pal, and beat it, ’cause you are going OUT!” The movie is based on a play by David Mamet, who once briefly worked in such a boiler room. He knows the way these people talk, and turns their jargon into a version of his own personal language, in which the routine obscenities and despair of everyday speech are transcribed into a sad music. Their struggle takes on a kind of nobility.

Look at Shelley (the Machine) Levene, for example. Played by Jack Lemmon, he was once a hotshot salesman, winning the office sweepstakes month after month. Now he is making no sales at all, and his wife is in the hospital, and it’s heartbreaking to hear his lies, about how he would feel wrong, not sharing this “marvelous opportunity.” Lemmon has a scene in this movie that represents the best work he has ever done. He makes a house call on a man who does not want to buy real estate. The man knows it, we know it, Lemmon knows it – but Lemmon keeps trying, not registering the man’s growing impatience to have him out of his house. There is a fine line in this scene between deception and breakdown, between Lemmon’s false jolity and the possibility that he may collapse right on the man’s rug, surrendering all hope.

The other salesmen are assembled in a well-balanced cast that rehearsed Mamet’s dialogue for weeks, getting to know the music of the words while working on the characters. Kevin Spacey is the office manager, unblinking and cold, playing by the rules. The salesmen are played by Al Pacino, Ed Harris, Alan Arkin and Lemmon. They are all in various stages of breakdown. There is a duet between Harris and Arkin that is one of the best things Mamet has written. They speculate about the near-legendary “good leads” that Spacey allegedly has locked in his office. What if someone broke into the office and stole the leads? Harris and Arkin discuss it, neither one quite saying out loud what’s on his mind.

There are other duets. Lemmon and Spacey have a scene in a car, in the rain, where Lemmon tries to buy the leads from Spacey.

And Pacino and Jonathan Pryce, who plays a possible customer, have a masterful scene in a restaurant booth, in which Pacino subtly tries to seduce Pryce into buying, by playing on what he senses is latent homosexuality.

In “Death of a Salesman,” Arthur Miller made the salesman into a symbol for the failure of the American dream. In Miller’s play, Willy Loman was out there all alone, on a smile and a shoeshine. “Glengarry Glen Ross” is a version for modern times.

Produced onstage in the good times of the 1980s, filmed in the hard times of the 1990s, it shows the new kind of American salesmanship, which is organized around offices and corporations. No longer is a salesman self-employed, going door-to-door. Now individual effort has been replaced by teamwork. The shabby Chicago real estate office, huddled under the L tracks, could be any white-collar organization in which middle-aged men find themselves faced with sudden and possibly permanent unemployment.

Having said that, I must not forget to mention the humor in the film. Mamet’s dialogue has a kind of logic, a cadence, that allows people to arrive in triumph at the ends of sentences we could not possibly have imagined. There is great energy in it. You can see the joy with which these actors get their teeth into these great lines, after living through movies in which flat dialogue serves only to advance the story. The film was directed by James Foley (“At Close Range“), whose timing and camera help underline the humor; a line of dialogue will end with a reaction shot that mirrors our own reaction – surprised, blind-sided, maybe a little stunned, but entertained by the zing of anger and ego in the words. While meanwhile nobody is buying any real estate, and it is raining, and the L thunders by like a mystery train to hell.