The squawks that Florence Foster Jenkins emits when straining for high notes sound as if she were a goose trying to lay an oversized egg after ingesting helium. Her pitch could not be any flatter if it were a bulldozed pancake found under a ton of bricks. During her lone public performance, she huffs and puffs and nearly blows down Carnegie Hall while committing auditory assault in the first degree.

But at some point while watching “Florence Foster Jenkins,” I can guarantee you will find yourself growing quite fond of this early 20th-century New York City dowager, despite her eardrum-puncturing delusions of being a Valkyrie-level opera singer. That’s because, in this charming and delightful biopic that bears her name, the matronly Jenkins is an endearing and courageous stand-in for countless other mortals whose aspirations in the arts often far exceed their talents.

Whereas most of us these days would simply settle for karaoke, Jenkins was in possession of a magic ingredient that helped make her performing wishes come true—money. Gobs of it, inherited from her father. As a generous and gracious promoter of music in many forms, Jenkins invested wisely. She was a chummy benefactor to the famous likes of conductor Arturo Toscanini and formed a club for her coterie of fans that included lunches overflowing with sandwiches and potato salad, ladled from an actual bathtub. She also had her own private nightspot where she staged living tableaus, including one that involved her precariously hanging from the ceiling attired as an angel while a team of men engaged in a titanic struggle to keep her plump form aloft by means of a pulley.

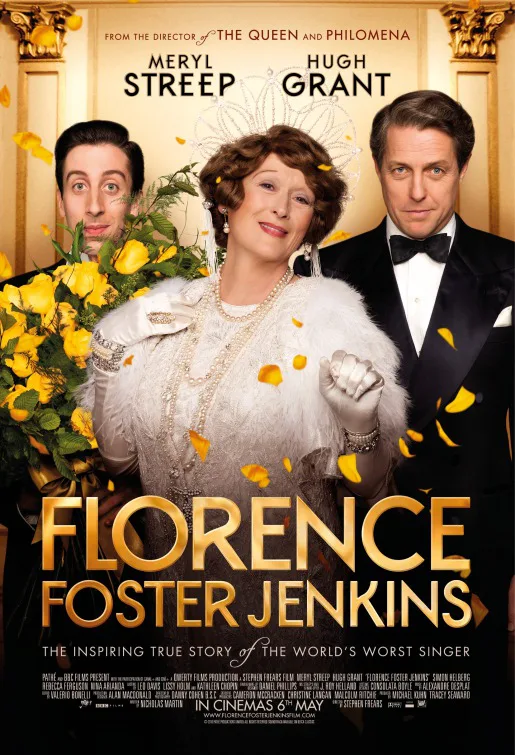

Jenkins is also blessed to have Meryl Streep, pulling off yet another miraculous physical transformation that is as delicious in its own way as was her joyful depiction of famed chef Julia Child in “Julie and Julia.” Oscar’s favorite diva relies on many of her usual tricks to not only nail the oft-times sweetly farcical elements embedded in the role, but also capture the poignancy of a 76-year-old woman who cherished music so much that she put her own health at risk in order to share her lifelong passion with others. With a broadened waistline, bonus facial wrinkles, an obvious wig to disguise a bald head and a wardrobe consisting of everyday frocks that resemble flowery tents or ornate senorita stage costumes, the actress puts all vanity aside and makes us believe she is this person.

Streep’s biggest triumph, however, is how she fully emulates her character’s unique vocal stridency. Her own early opera training comes in handy here—and when a recording of Jenkins is heard before the end credits, it becomes astonishingly clear just how skilled Streep is at singing badly.

She also is not alone in breathing life into what could have simply been a fusty little old lady period piece. British director Stephen Frears, who has previously proven to be adept at showcasing wonder women of a certain age (Helen Mirren in “The Queen,” Judi Dench in “Mrs. Henderson Presents” and “Philomena”), coaxed Hugh Grant out of semi-retirement to play Jenkins’ devoted common-law husband St. Clair Bayfield. It’s a good thing he did, too, since Grant gives one of his finest performances ever.

At first, it is easy to be suspicious of Bayfield, a middling Shakespearean actor, whose primary purpose is to dote on Jenkins, indulge her every whim and shield her from hearing any harsh reaction to her rancid arias. Grant has done his fair share of cads over the years. Is he just a gigolo plundering her riches for his own gains, especially since he keeps a separate apartment complete with a much younger mistress? But it becomes apparent soon enough that there is a deep and sincere connection between the pair as he tenderly calls her “bunny rabbit” and she flutters in her devoted protector’s presence like a giddy schoolgirl.

And where has this comedic prodigy Simon Helberg been hiding all this time? On TV’s “The Big Bang Theory” for 10 seasons, that’s where. What Alden Ehrenreich was to “Hail, Caesar!” earlier this year—a standout amongst stars—that is what Helberg is as Cosme McMoon, Jenkins’ shy, pigeon-chested accompanist who is often on the verge of full-out hysteria when not stifling giggles over his employer’s warbling deficiencies. He, too, acquires a respectful affection for Jenkins, as revealed in a quiet scene where they perform an intimate Chopin piano duet that is touching enough to draw tears.

The story itself is intriguing but veers too far towards the overtly sentimental as it concludes. But in a rather off-key summer movie season heavy on rehashed material, “Florence Foster Jenkins” will strike a chord with those looking for relief in the form of originality, top-tier acting and amazingly godawful singing. An extra bonus? The sense of kindness afforded to its central grand dame, a commodity that has been short supply of late as an ugly, insult-filled political contest marches on.