Sex for money sometimes conceals great sadness. It can be sought to treat wounds it cannot heal. I believe that may happen less in actual prostitution than in the parody of prostitution offered in “gentleman’s clubs.” Whatever is going on is less about sex than psychological need, sometimes on both sides. Atom Egoyan‘s “Exotica” is a deep, painful film about those closed worlds of stage-managed lust.

It is also a tender film about a lonely and desperate man, and a woman who is kind to him. How desperate and how kind are only slowly revealed. In a technical sense, this is a “hyperlink movie,” in which characters are revealed to be connected in ways they may not know about. But Egoyan, who also wrote the film, surprises us in how slowly he reveals the links and even more slowly reveals what the characters know about them. When the film ends, you sit regarding the screen, putting together what you have just learned and using it to think again about what went before.

The critic Bryant Frazer wrote that after the film played in the 1994 New York Film Festival, a woman asked Egoyan what had happened at the end. Egoyan was “visibly perturbed” by the question, he said, but finally responded. Frazer writes, “Here is what the last scene in the film meant, he explained, his four- or five-word declamation a stark and numbing negation of the gentle, almost languid spirit of the film, which invites the audience to its own discovery. The ‘what happened’ is simple enough to explain, but you can’t really understand it unless you’re fully caught up in the cinema when it unfolds in front of you.”

Frazer is right: There is no mystery at the end, except the mysteries of human nature that Egoyan evokes. What you think about those will define the film’s importance to you. For me, they make it a cry of sympathy for people suffering from loss and guilt, and also an affirmation about how others are wiling to understand them. A film can only get so far by simply stating its message; if the message is that easily defined, why bother with the film? “Exotica” does what many good films do and implies its troubled feelings. Nothing is solved at the end, except that we have learned to understand the characters.

“Exotica” takes place in a Toronto strip club, but not one of those hellholes of expense account executives and drunken bachelor parties. This club seems to fill the special needs of the men who go there, although we learn only about one. He is Francis (Bruce Greenwood), who every night buys the company of Christina (Mia Kirshner). She looks young, dresses in a school uniform, opens her shirt before him, and then they talk softly and intensely.

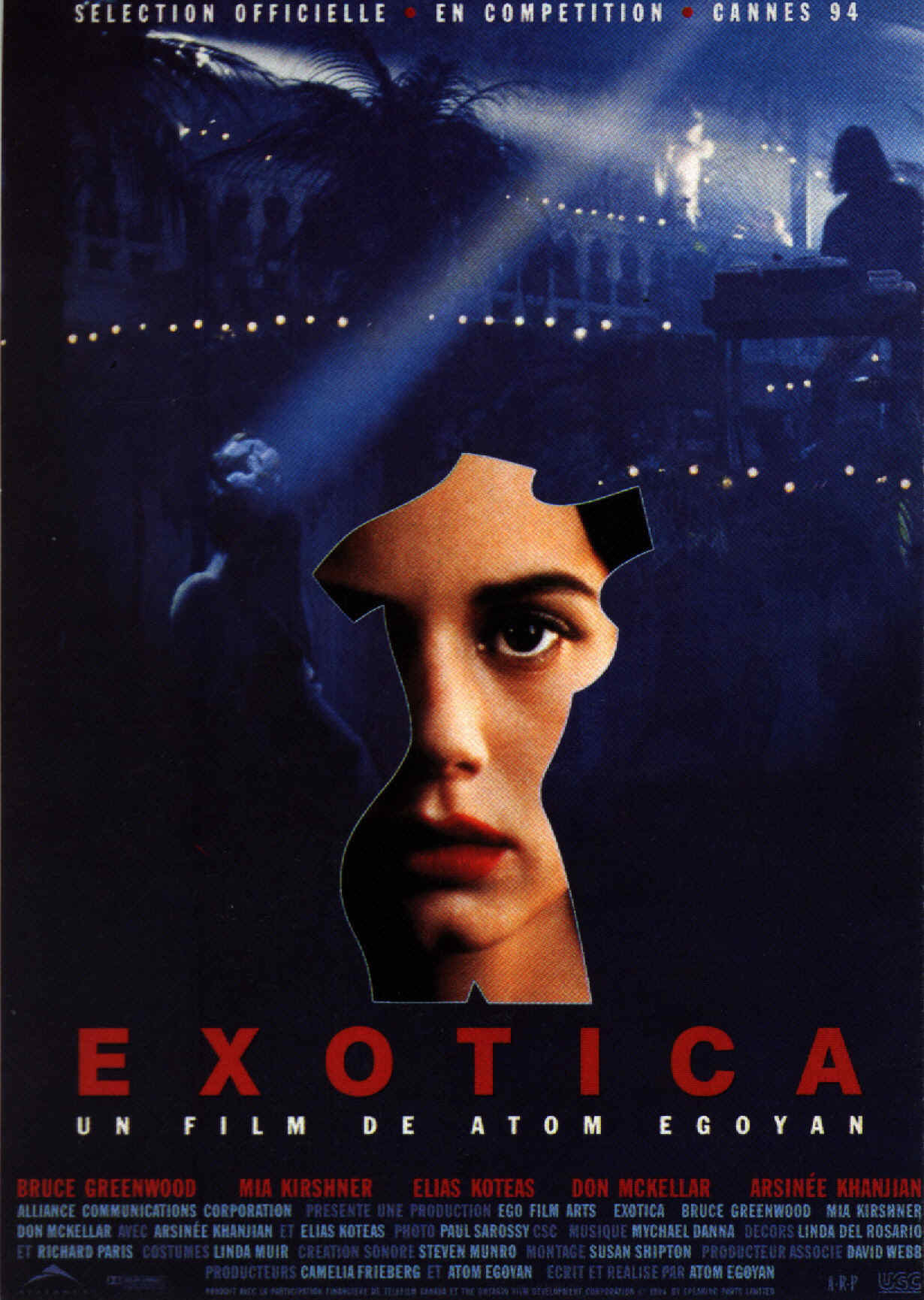

Watching this is the club DJ, Eric (Elias Koteas), who stands on a perch above the action and contributes an insinuating commentary on the lives below. Also watching, from behind one-way mirrors, is the pregnant Zoe (Arsinée Khanjian), who inherited the club from her mother. The decor creates a tropical club heavy with palm fronds, the music slinks between the tables, the lighting is an oddly muted garishness, gloom cut with neon reds, greens and blues. Egoyan’s camera glides around the room, pausing to regard Francis and Christina. Whatever they’re talking about hardly seems to be sex and seems to absorb them equally. The DJ notices this.

Other characters are implicated. The opening shots of the film show customs officers scrutinizing an arrival on a flight from the Far East, through a one-way mirror. This is Thomas, whom we discover is smuggling rare macaw eggs. At the airport, a man suggests they share a ride to town and pays his share of the ride with two ballet tickets. Thomas gives one of the tickets to a good-looking gay man outside the theater, and they eventually spend the night together. The man was one of the customs officers. He confiscates the eggs, but wants to see Thomas again. Thomas’ pet shop is audited under suspicion of illegal imports — by Francis, who later wants him to help eavesdrop on Christina. You see how the subterranean connections link.

I have made “Exotica” seem to be all complexities. Following the connections is straightforward. Deciding what they mean is the challenge. Egoyan has not unfolded the plot as simply as I summarized it, and he uses other suggestive characters. There is Tracey (Sarah Polley, then 15), the young girl Francis hires every night to baby-sit while he is visiting the club. But it’s other than baby-sitting. At the club. he’s a client of Christina, who dresses as a schoolgirl; does this suggest he has a sexual interest in Tracey? What does Tracey’s father think of the arrangement?

Enough of the plot. Let’s draw back to admire Egoyan’s method. If we do not at first understand all of the relationships between the characters, they do not all understand them themselves, and in certain ways never figure them out. That provides the film with hidden emotional currents as powerful as those that are visible. When you think through the film later, you realize how much some of the characters never know, and yet how important it has been to the outcome. Egoyan isn’t weaving these strands simply to divert us with a labyrinth; he is suggesting the hidden ways in which we affect other lives with our choices and behavior even though unaware.

Beneath everything pulses the atmosphere of the club Exotica, its promise of sexuality masking deeper needs and obsessions. The grave voice of Leonard Cohen and the starkness of his songs, played by Eric the DJ, seem wrong for a strip club, but not for this one, where not desire but desperation is catered to. The advertising, selling a sexy thriller, is all wrong.

Zoe, the club owner, is in some ways the spirit of the film. She is very pregnant, very happy about it, very convinced that her mother created the club in a special way for a special clientele with special needs. She knows more about some of the clients than they realize. She is worried about the tension between Eric and Christina. She meets with Francis after he is thrown out of the club. She wants to restore peace and order, and I won’t tell you why that is so difficult for her.

Atom Egoyan, born in 1960 in Egypt of Armenian parents, brought up in Canada, has consistently stepped outside the mainstream in style and subjects. He’s fascinated by how people are kept separated by the realities of culture (ethnicity, gender, background) and walls of images, and how they try to get through or around them. One of the most uncompromising of major directors, he hasn’t made a single film for solely commercial reasons.

Egoyan is best known for “The Sweet Hereafter,” which won the grand jury prize at Cannes 1997; “Felicia's Journey” (1998), and “Where the Truth Lies,” that remarkable 2005 film with Kevin Bacon and Colin Firth as a team not unlike Dean Martin and Jerry Lewis, implicated in a murder. He often works with his wife, Arsinee Khanjian, who like Ingrid Bergman has the ability to project carnality and sweetness simultaneously. Egoyan brought his first feature, the $20,000 “Next of Kin,” to the Toronto Film Festival in 1984. He was only 24.

There is a quality in all of his work that resists the superficial and facile. Even at the very start, he wasn’t interested in simple storytelling. He is drawn to what Fitzgerald called the dark night of the soul. Secrets, shames, the hidden and the forbidden coil around his characters, but he is not quick to condemn them. He and Khanjian are warm, friendly and smile easily, and in the films, you sense love for the characters and the belief that to know more is to forgive more.

“Exotica” is a Miramax Classics DVD. Most of Egoyan’s films are reviewed at rogerebert.com.