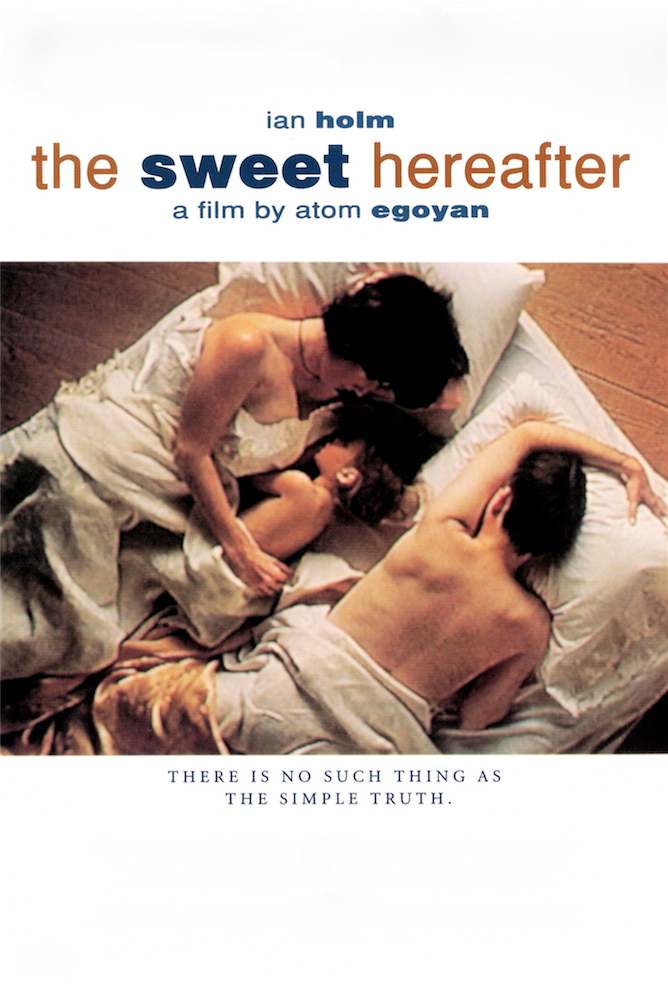

A cold, dark hillside looms above the Bide-a-Wile Motel, pressing down on it, crushing out the life with the gray weight of winter. It is one of the strongest images in Atom Egoyan’s “The Sweet Hereafter,” which takes place in a small Canadian town, locked in by snow and buried in grief after 14 children are killed in a school bus accident.

To this town comes a quiet man, a lawyer who wants to represent the residents in a class action suit. Mitchell Stephens (Ian Holm) lacks the energy to be an ambulance chaser; he is only going through the motions of his occupation. In a way he’s lost a child, too; the first time we see him, he’s on the phone with his drug-addicted daughter. “I don’t know who I’m talking to right now,” he tells her.

There will be no victory at the end, we sense. This is not one of those Grisham films in which the lawyers battle injustice and the creaky system somehow works. The parents who have lost their children can never get them back; the school bus driver must live forever with what happened; lawsuits will open old wounds and betray old secrets. If the lawyer wins, he gets to keep a third of the settlement; one look in his eyes reveals how little he thinks about money.

Egoyan’s film, based on the novel by Russell Banks, is not about the tragedy of dying, but about the grief of surviving. In the film the Browning poem about the Pied Piper is read, and we remember that the saddest figure in that poem was the lame boy who could not join the others in following the piper. In “The Sweet Hereafter,” an important character is a teenage girl who loses the use of her legs in the accident; she survives, but seems unwilling to accept the life left for her.

Egoyan is a director whose films coil through time and double back to take a second look at the lives of their characters. It is typical of his approach that “The Sweet Hereafter” neither begins nor ends with the bus falling through the ice of a frozen lake, and is not really about how the accident happened, or who was to blame. The accident is like the snow clouds, always there, cutting off the characters from the sun, a vast fact nobody can change.

The lawyer makes his rounds, calling on parents. Egoyan draws them vividly with brief, cutting scenes. The motel owners, Wendell and Risa Walker (Maury Chaykin and Alberta Watson), fill him in on the other parents–Wendell has nothing good to say about anyone. Sam and Mary Burnell (Tom McCamus and Brooke Johnson) are the parents of Nicole, the budding young country-music singer who is now in a wheelchair. Wanda and Hartley Otto (Arsinee Khanjian and Earl Pastko) lost their son, an adopted Indian boy. Billy Ansell (Bruce Greenwood) was following the bus in his pickup and waved to his children just before it swerved from the road. He wants nothing to do with the lawsuit and is bitter about those who do. He is having an affair with Risa, the motel owner’s wife.

This story is not about lawyers or the law, not about small-town insularity, not about revenge (although that motivates an unexpected turning point). It is more about the living dead–about people carrying on their lives after hope and meaning have gone. The film is so sad, so tender toward its characters. The lawyer, an outsider who might at first seem like the source of more trouble, comes across more like a witness, who regards the stricken parents and sees his own approaching loss of a daughter in their eyes.

Ian Holm’s performance here is bottomless with its subtlety; he proceeds doggedly through the town, following the routine of his profession, as if this is his penance. And there is a later scene, set on an airplane, where he finds himself seated next to his daughter’s childhood friend, and remembers, in a heart-breaking monologue, a time in childhood when his daughter almost died of a spider bite. Is it good or bad that she survived, in order now to die of drugs? Egoyan sees the town so vividly. A hearing is held in the village hall, where folding tables and chairs wait for potluck dinners and bingo nights. A foosball table is in a corner. In another corner, Nicole, in her wheelchair, describes the accident. She lies. It is too simple to say she lies as a form of getting even, because we wonder–if she were not in a wheelchair, would she feel the same way? Does she feel abused, or scorned? “You’d make a great poker played, kid,” the lawyer tells her.

This is one of the best films of the year, an unflinching lament for the human condition. Yes, it is told out of sequence, but not as a gimmick: In a way, Egoyan has constructed this film in the simplest possible way. It isn’t about the beginning and end of the plot, but about the beginning and end of the emotions. In his first scene, the lawyer tells his daughter he doesn’t know who he’s talking to. In one of his closing scenes, he remembers a time when he did know her. But what did it get him?