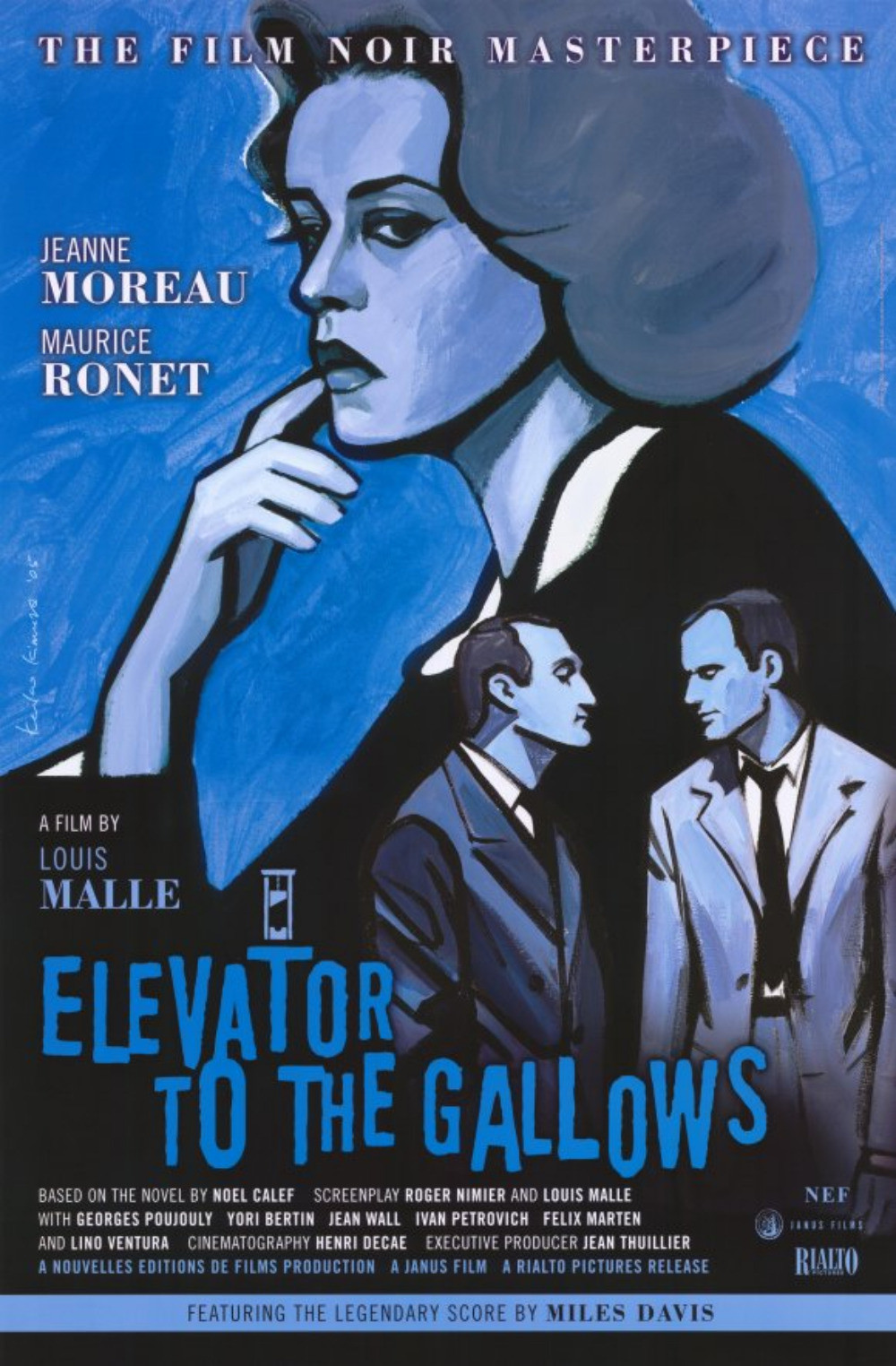

She loves him. “Je t’aime, je t’aime,” she repeats into the telephone, in the desperate closeup that opens Louis Malle’s “Elevator to the Gallows” (1958). He needs to know this, because he is going to commit a murder for them. The woman is Jeanne Moreau, in her first role, [sic—Ed.] looking bruised by the pain of love. She plays Florence, wife of the millionaire arms dealer Simon Carala (Jean Wall). Her lover, Julien Tavernier (Maurice Ronet), is a paratrooper who served in Indochina and Algeria, in wars that made Carala rich. Now he works for Carala, and is going to kill him and take his wife.

Because Julien has access and a motive, he must make this a perfect crime. Malle, who apprenticed with the painstaking genius Robert Bresson, devotes loving care to the details of the murder. After office hours, Julien uses a rope and a hook to climb up one floor and enter a window of Simon’s office. He shoots him, makes it look like a suicide, bolts the office from inside, leaves by the window. An elegant little Locked Room Mystery. Then he climbs back down and leaves to meet his mistress.

Stupidly, he has left behind evidence. It is growing dark. Perhaps no one has noticed. He hurries back to the office and gets into an elevator, but then the power is shut off in the building for the night, and he is trapped between floors. Florence, meanwhile, waits and waits in the cafe where they planned their rendezvous. And then, in a series of shots that became famous, she walks the streets, visiting all their usual haunts, looking for the lover she is convinced has deserted her.

Moreau plays these scenes not with frantic anxiety, but with a kind of masochistic despair, not really expecting to find Julien. It rains, and she wanders drenched in the night. Malle shot her scenes using a camera in a baby carriage pushed along beside her by the cinematographer Henri Decae, who worked with Jean-Pierre Melville on another great noir of the period, “Bob le Flambeur” (1955). Her face is often illuminated only by the lights of the cafes and shops that she passes; at a time when actresses were lit and photographed with care, these scenes had a shock value, and influenced many films to come. We see that Florence is a little mad. An improvised jazz score by Miles Davis seems to belong to the night as much as she does.

Meanwhile, Julien struggles to free himself from the elevator. There is a parallel story. His parked car is stolen by a teenage couple — the braggart Louis (Georges Poujouly) and his girlfriend Veronique (Yori Bertin). They get into a fender-bender with a German tourist and his wife, and the tourists rather improbably invite them to party with them at a motel. This leads to murder, and the police of course suspect Julien because his car is found at the scene.

The more I see the great French crime films of the 1950s, the earlier seems the dawning of the New Wave. The work of Melville, Jacques Becker and their contemporaries uses the same low-budget, unsprung, jumpy style that was adapted by Truffaut in “Jules and Jim” and Godard in “Breathless” (which owes a lot to the teenage couple in “Elevator”). Malle became a card-carrying New Waver, and “Elevator to the Gallows” could be called the first New Wave title, except then what was “Bob le Flambeur”?

These 1950s French noirs abandon the formality of traditional crime films, the almost ritualistic obedience to formula, and show crazy stuff happening to people who seem to be making up their lives as they go along. There is an irony that Julien, trapped in the elevator, has a perfect alibi for the murders he is suspected of, but seems inescapably implicated with the one he might have gotten away with. And observe the way Moreau, wandering the streets, handles her arrest for prostitution. She is so depressed it hardly matters, and yet, is this the way the wife of a powerful man should be treated? Even one she hopes is dead?

Note: The movie is playing at the Music Box and around the country in a beautifully restored 35-mm print that works as a reminder: Black and white doesn’t subtract something from a film, but adds it.