“Cosmopolis” is a flawlessly directed film about enigmatic people who speak in morose epigrams about vague universal principles they show no sign of understanding. Its characters are bloodless, their speech monotone. If there are people like this, I hope David Cronenberg‘s film is as close as I ever get to them. You couldn’t pay me to see it again.

The movie stars Robert Pattinson, as Eric Packer, a loathsome billionaire monster, a young master of Wall Street who seems to perceive no connection between his wealth and its results in the world. He has sex several times in the film and reveals less genuine passion than during a prostate examination. During the course of a day, his fortune seems to be melting away, hemorrhaging millions a minute, but c’est la vie. He has recently married a rich woman who assures him she can help him, and he regards her with the detachment of an incurious insect. The movie is based on a novel by Don DeLillo, which I read and rather admired. It’s said to be loosely inspired by James Joyce’s Ulysses. Very loosely. Yes, it involves the hero’s journey across a city during a single day, and yes, it hears several vernaculars. But the film and the novel both lack any trace of Joyce’s humor and rich humanity. Here is a stark, forbidding portrait of the damned in a hell of their making.

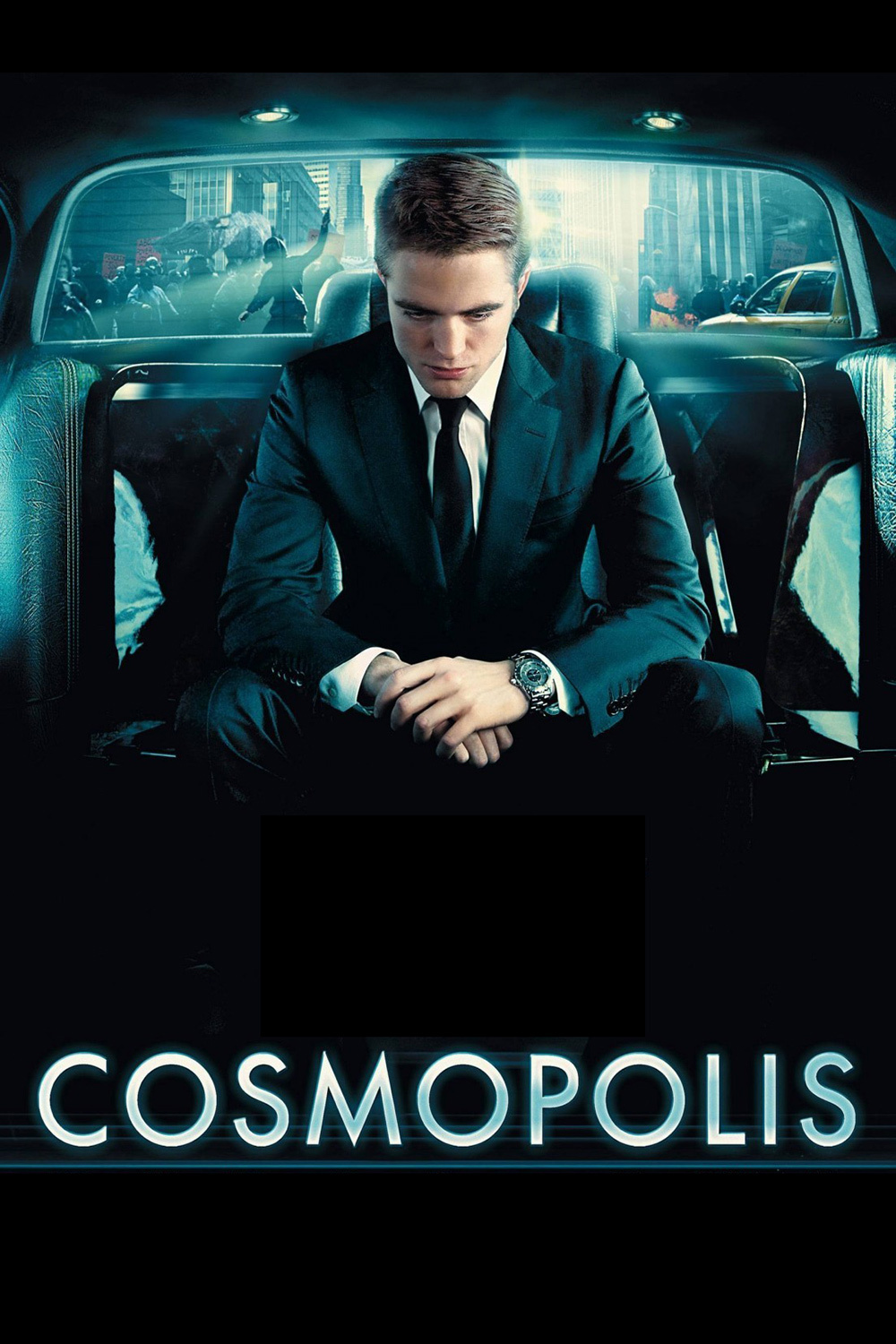

As the film opens, Packer stands on the sidewalk in front of what is possibly his office tower and states without emotion, “We need a haircut.” As Pattinson plays Packer, he states everything without emotion. All of the criticisms you may have heard or held about Pattinson’s performances as the vampire Edward in the “Twilight” (2008) films only serve to underline that he is perfectly cast as Packer.

He enters his improbably long white stretch limousine, lengthy enough for a Mafia wedding, and sets off across Manhattan to his usual barbershop. It is not a good day for this journey. The city is experiencing gridlock cubed, because of a presidential motorcade, a rap star’s funeral and anarchist riots. Packer doesn’t care, and he, and we, will spend from morning to night mostly inside the limousine.

But not entirely. Traffic is moving so slowly that he finds time to have both breakfast and lunch with his new wife, Elise (Sarah Gadon). One of the mysteries of the novel is how he inexplicably encounters her along the way. He welcomes inside the limo his mistress, Didi (Juliette Binoche); two consultants (Jay Baruchel and Philip Nozuka), his chief theoretician, Vija (Samantha Morton), and his doctor, who not only administers the prostate exam during his conference with Vija, but also uses the limo’s built-in technology to conduct sonar exams. There is also a hotel suite tryst with his beautiful security guard, who teases him with a 100,000-volt taser that may remind you of Goldfinger’s laser beam. “Hit me with it,” Packer asks her. “I want to experience it.”

The limo is a command center with touch-screen displays that have the world’s financial transactions rattling past. One of Cronenberg’s achievements here is to shoot so many scenes inside this vehicle without ever seeming crowded, cramped or limited. The limo is of course bulletproof and so on, but there’s a dicey moment when anarchists surround it and begin to rock it back and forth. Packer doesn’t deign to acknowledge them. Not so easily ignored is a man who smashes a pie in his face as he arrives at last at the barbershop.

The final act involves a nutty little man named Benno Levin (Paul Giamatti), who opens fire on him from a warehouse in the district where limos go to spend the night. How did he know Packer would be there? How did Packer know how to find him in the warehouse? I knew better than to ask, as they conduct the film’s deepest, most philosophical and impenetrable conversation.

I said “Cosmopolis” is flawlessly directed. Yes, it is. I can’t easily imagine a better screen version of the DeLillo novel, although I don’t much want to imagine one at all. David Cronenberg is a master filmmaker, whose films sometimes fail to reverberate with me, but whose genius cannot be denied. There is a coldness and abstraction in much of his work, a heartlessness. He touched me deeply in films like “Eastern Promises,” “The Fly,” “The Dead Zone” and even the pain-soaked “Crash.” Then there are films like this. Can one say Don DeLillo found not only the ideal but perhaps the only director for his novel.