David Cronenberg’s “Eastern Promises” opens with a throat-slashing and a young woman collapsing in blood in a drugstore, and connects these events with a descent into an underground of Russians who have immigrated to London and brought their crime family with them. Like the Corleone family, but with a less wise and more fearsome patriarch, the Vory V Zakone family of the Russian mafia operates in the shadows of legitimate business — in this case, a popular restaurant.

The slashing need not immediately concern us. The teenage girl who hemorrhages is raced to a hospital and dies in childbirth in the arms of a midwife named Anna Khitrova (Naomi Watts). Fiercely determined to protect the helpless surviving infant, she uses her Russian-born mother and uncle (Sinead Cusack and Jerzy Skolimowski) to translate the dead girl’s diary, and it leads her to a restaurant run by Semyon (Armin Mueller-Stahl), the head of the mafia family. Her uncle begs her to go nowhere near that world.

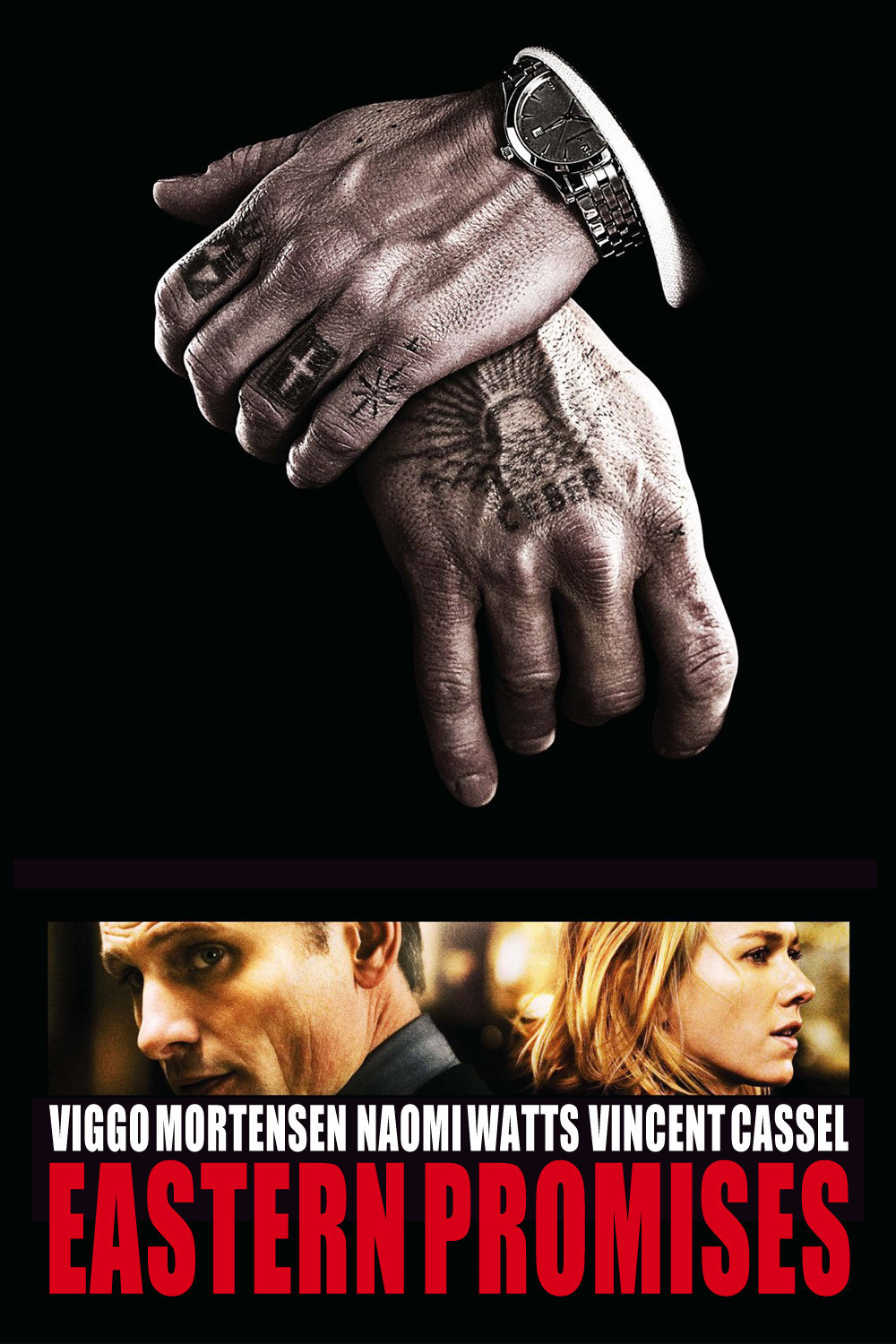

Semyon has a vile son named Kirill (Vincent Cassel) and a violent but loyal driver and bodyguard, Nikolai (Viggo Mortensen). And the gears of the story shift into place when the diary, the midwife and the crime family become interlocked.

“Eastern Promises” is no ordinary crime thriller, just as Cronenberg is no ordinary director. Beginning with low-rent horror films in the 1970s, because he could get them financed, Cronenberg has moved film by film into the top rank of directors, and here he wisely reunites with Mortensen, star of their “A History of Violence” (2005). No, Mortensen is not Russian, but don’t even think about the problem of an accent; he digs so deeply into the role you may not recognize him at first.

Naomi Watts, playing an Anglicized second-generation immigrant, has no idea at first what she has gotten herself into, and why the diary is of vital importance to these people. All she cares about is the baby, but she learns fast that the baby’s life and her own are both at great risk. In fact, her entry into that world has driven a wedge into it that sets everybody at odds and challenges long-held assumptions.

The script is by Steven Knight, author of the powerful “Dirty Pretty Things” (2002), about a black market in body parts. Set in London, it had scarcely a native-born Londoner in it. He’s fascinated by the worlds within the London world. Here, too. His lines of morality are more murkily drawn here, as allegiances and loyalties shift, and old emotions turn out to be forgotten but not dead.

Mortensen’s Nikolai is the key player, trusted by Semyon. We are reminded of Don Corleone’s trust in an outsider, Tom Hagen, over his own sons, Sonny and Fredo. Here Semyon depends on Nikolai more than Kirill, who has an ugly streak that sometimes interferes with the orderly conduct of business. Anna (Watts) senses she can trust Nikolai, too, even though it is established early that this tattooed warrior is capable of astonishing violence. At a time when movie “fight scenes” are as routine as the dances in musicals, Nikolai engages in a fight in this film that sets the same kind of standard that “The French Connection” set for chases. Years from now, it will be referred to as a benchmark.

Cronenberg has said he’s not interested in crime stories as themselves. “I was watching ‘Miami Vice’ the other night,” he told Adam Nayman of Toronto’s Eye Weekly, “and I realized I’m not interested in the mechanics of the mob, but criminality and people who live in a state of perpetual transgression — that is interesting to me.”

And to me as well. What the director and writer do here is not unfold a plot, but flay the skin from a hidden world. Their story puts their characters to a test: They can be true to their job descriptions within a hermetically sealed world where everyone shares the same values and expectations, and where outsiders are by definition the prey. But what happens when their cocoon is broached? Do they still possess fugitive feelings instilled by a long-forgotten babushka? And what if they do?

“Just don’t give the plot away,” Cronenberg begged in that interview. He is correct that it would be fatal, because this is not a movie of what or how, but of why. And for a long time you don’t see the why coming. It’s that way with stories about plausible human beings, which is why I prefer them to stories about characters who are simply elements in fiction. There was a big surprise in “A History of Violence” that pretty much everybody entering the theater already knew. But “Eastern Promises” had its world premiere Saturday at the Toronto Film Festival and opens today in major North American markets; I have studied its trailer, and it doesn’t give away a hint of its central business.

So let’s leave it that way and simply regard the performances. I write little about casting directors, because I can’t know what really goes on, and of course directors make the final choice for key roles. But whatever Deirdre Bowen and Nina Gold had to do with the choices in this movie, including what might seem the unlikely choice of Mortensen, was pitch-perfect. The actors and the characters merge and form a reality above and apart from the story, and the result is a film that takes us beyond crime and London and the Russian mafia and into the mystifying realms of human nature.