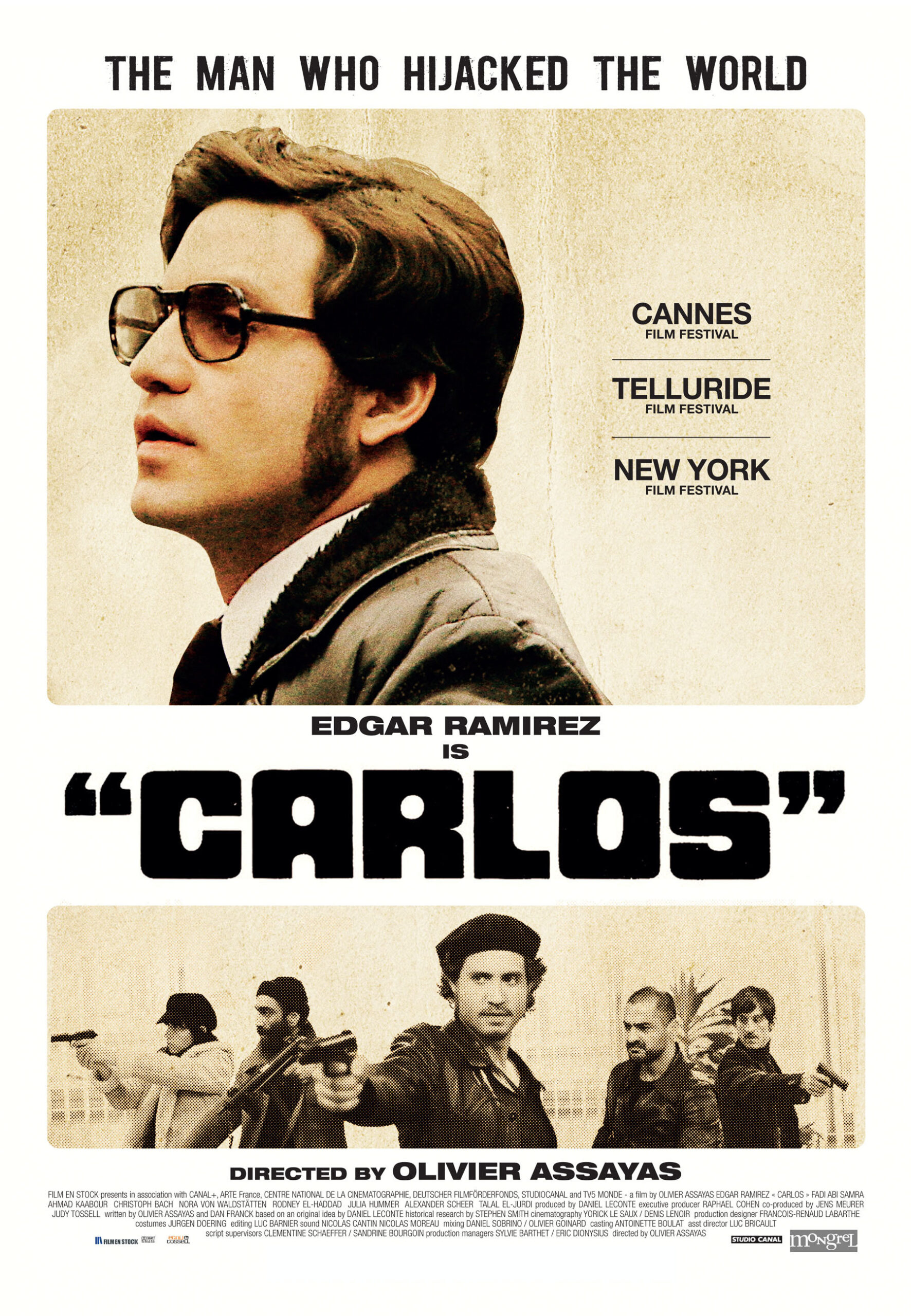

The man known as Carlos the Jackal said that Marxism was his religion and that he was dedicated to the Palestinian cause. Having seen the long version of Olivier Assayas’ remarkable “Carlos,” I conclude that for Carlos his religion and his cause were the same, and they were himself. This is a terrifying portrait of an egomaniac who demands absolute obedience, and craves it even more when his power and relevance are drained away. All he has left at the end are a few pathetic nonentities who obey him.

If Carlos is a shabby excuse for a great man, “Carlos” is nonetheless a powerful film from recent history, considering in (largely fictionalized) detail how the myth of Carlos shadowed the years from 1975, when he led a raid on OPEC oil ministers in Vienna, until 1994, when he was betrayed by former comrades, arrested in Sudan and returned to France for trial. He is now serving a life sentence and from prison has complained that this film is inaccurate.

I have no knowledge of the real Carlos and can only review the film. On that basis, Ilich Ramirez Sanchez, a Venezuelan born in 1949 and educated at a Cuban training camp and Patrice Lumumba University in Moscow, used his ideology primarily to dominate others and excuse his megalomania. Toward the end, even his superiors in the Palestinian liberation movement were fed up with him, and after exhausting the hospitality of Libya, Syria and Iraq, he became a man without a country.

Carlos is played by Edgar Ramirez, an actor of great vitality and conviction. He speaks five languages, and in “Carlos,” he performs dialogue in even more, as he functions in France, Spain, Germany, Egypt, Iraq, Russia and North Africa. (The film is largely in English, the international language of terrorism.) Without using any apparent makeup tricks, he successfully ages from a young hot-head to a middle-age “Syrian businessman” with a nice little pot belly, while passing through a period when he is lean and muscular after guerrilla training. His side burns flourish and disappear, beards and mustaches come and go, and yet clearly he is Carlos if you take a good look. He passed through many passport controls where apparently nobody did, though once years ago at London’s Heathrow, I was pulled aside on suspicion of being Carlos. He ran on the plump side, for a jackal.

In notes and anonymous phone calls taking blame (or “credit”) for bombings, murders and missile attacks, he identified his group as “the armed branch of the Palestinian Liberation Struggle.” I have no idea what the reality was. In the film, this group seems to consist largely of himself as the autarch of a small group of submissive followers who had loose connections with better-organized cells in Germany and France. He was well-financed by mischievous governments, including the Soviet Union, East Germany and Iraq, shipped crates of weapons by using diplomatic immunity, lived in swank hotels, safe houses or borrowed apartments.

His “operations” seem almost anarchic. He and his followers have the strategy of walking in armed and doing what they intend. In a public observation area at an airport, surrounded by others, they attempt to deploy a rocket launcher to blow up airplanes. Their getaway strategy usually comes down to get the hell outta there. He got his nickname from the Frederick Forsyth novel “The Day of the Jackal,” but the hero of the excellent Fred Zinnemann film of that name takes meticulous care in his planning. Carlos seems impulsive. It’s extraordinary how long he survived on the run.

His major operation was the OPEC raid. He took 42 hostages and demanded an airplane to take them to Algiers. That led to an odyssey on to Baghdad and Tripoli before returning to Algiers. Assayas is at his best showing this undertaking, during which Carlos fails to execute two of the oil ministers as ordered and is berated by his superior in the movement, Wadie Haddad (Ahmad Kaabour). Then as later, his personal fame and publicity were felt to distract from the focus of the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine.

Did he care deeply about Palestine? I get the impression that he cared deeply about seeming to care deeply. His personality would have been equally well suited to any other revolutionary struggle. He hated any authority except his own, and granted himself life and death power over others because — well, because he was Carlos. Given the opportunity. he might have made a Stalin, Hitler or Pol Pot.

Much of the film is devoted to the periods between action. We meet the private Carlos, whose sexuality depends on the conquest and domination of women. He is enabled by a long-suffering girlfriend and wife, Magdalena Kopp (Nora von Waldstatten), before they have a child, and she walks out for the child’s sake. Also by a series of mistresses, especially Nada (Gabriele Krocher-Tiedemann), who stands by him during a painful illness with a testicular tumor. It is an insight into Carlos’ ego that he postponed tumor surgery for a more important operation: liposuction.

That he satisfies women sexually there seems no doubt. They accept, not always happily, his many affairs with others, including prostitutes. He is such a great man he is exempt from ordinary behavior. All along the way, he is accompanied by his sidekick, Hans-Joachim Klein (Christoph Bach), an uncertain man with a wispy mustache, who has a way of drinking himself unconscious, not a valuable trait in a terrorist. When the two of them party with hookers in East Berlin, they’re too naive to suspect they’re plants by the secret police.

“Carlos” exists in three formats. The theatrical version runs 165 minutes; there’s a road-show version in two parts totaling 332 minutes. The full three-part miniseries, totaling 5:35, played on the Sundance Channel. Some theaters, such as Chicago’s Music Box, will show the film in the 165- and 332-minute versions. I saw the longest, and I was not bored. Assayas doesn’t make the mistake of wearing us out with action, which in excess is simply boring; he’s fascinated by the minutiae of daily routine in the life of a wanted and hated man.

There is a detail I must mention: I have never seen more smoking in a movie. Every character smokes heavily, and Carlos constantly, indeed distractingly. No doubt this is based on fact, but what does Assayas mean by depicting it so pointedly? It shows Carlos addicted to quick and constant fixes. He never shows any pleasure in smoking. He simply has to do it. It may be a metaphor for terrorism.