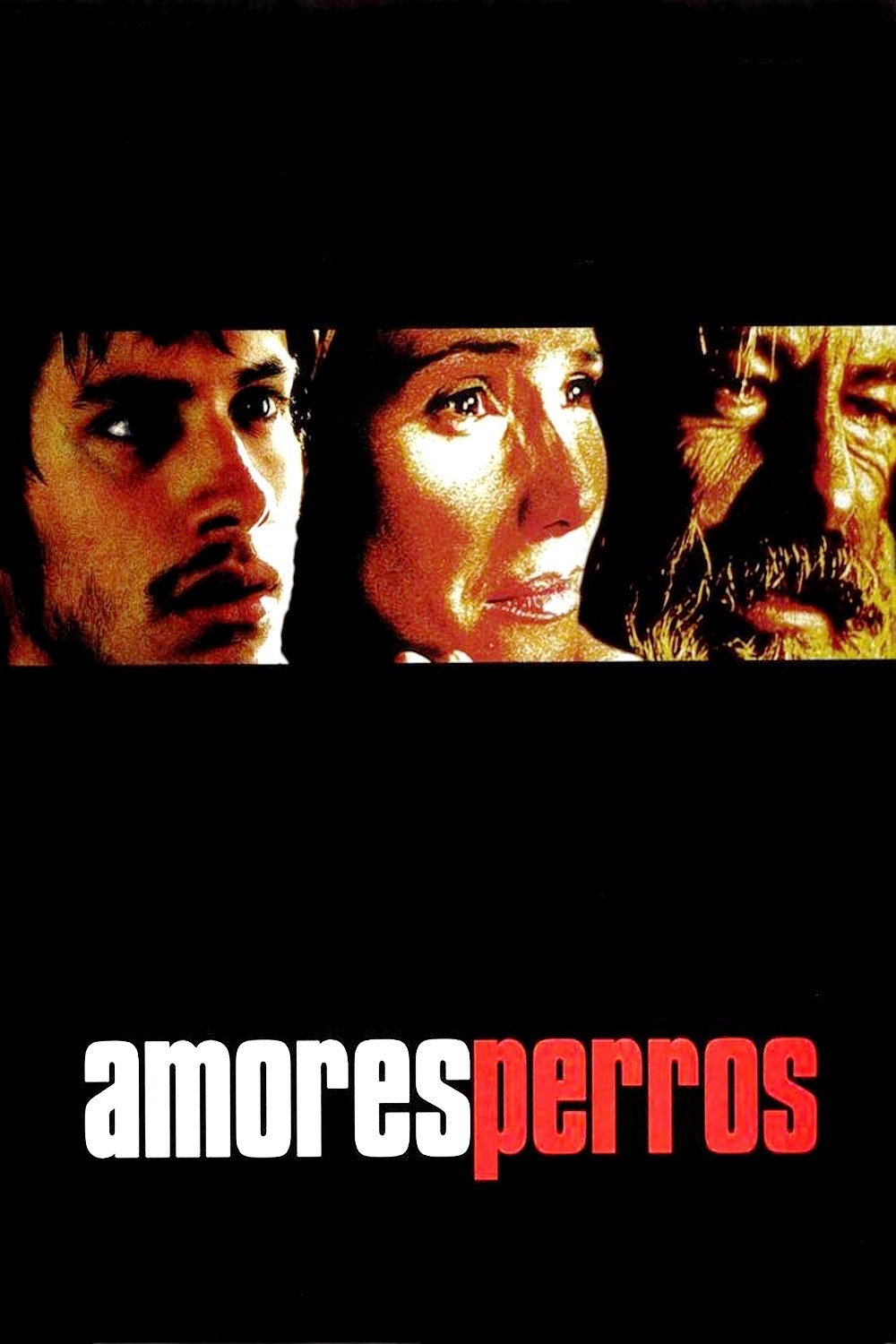

“Amores Perros” arrives from Mexico trailing clouds of glory–it was one of this year’s Oscar nominees–and generating excitement on the Internet, where the fanboys don’t usually flip for foreign films. It tells three interlinked stories that span the social classes in Mexico City, from rich TV people to the working class to the homeless, and it circles through those stories with a nod to Quentin Tarantino, whose “Pulp Fiction” had a magnetic influence on young filmmakers.

Many are influenced but few are chosen: Alejandro Gonzalez Inarritu, making his feature debut, borrows what he can use, but is an original, dynamic director.

The title, loosely translated in English, is “Love’s a Bitch,” and all three of his stories involve dogs who become as important as the human characters. The film opens with a disclaimer promising that no animals were harmed in the making of the film. That notice usually appears at the ends of films, but putting it first in “Amores Perros” is wise, since the first sequence involves dog fights and all three will be painful for soft-hearted animal lovers to sit through.

“Octavio and Susana,” the first segment, begins with cars hurtling through city streets in a chase and gunfight. The images are so quick and confused, at first we don’t realize the bleeding body in the back seat belongs to a dog. This is Cofi, the beloved fighting animal of Octavio (Gael Garcia Bernal), a poor young man who is helplessly in love with Susana (Vanessa Bauche), the teenage bride of his ominous brother Ramiro (Marco Perez). Flashbacks show how Cofi was shot after killing a champion dog; now the chase ends in a spectacular crash in an intersection–a crash that will involve all three of the movie’s stories.

In the second segment, “Daniel and Valeria,” we meet a television producer (Alvaro Guerrero) who has abandoned his family to live with a beautiful young model and actress (Goya Toledo). He’s rented a big new apartment for her; Valeria’s image smiles in from a billboard visible through a window. But then their happiness is marred when Valeria’s little dog chases a ball into a hole in the floor, disappears under the floorboards and won’t return. Is it lost, trapped or frightened? “There are thousands of rats down there,” Valeria wails to Daniel.

We discover that Valeria was involved in the crash that begins the movie; we see it this time from a different angle, and indeed it comes as a shock every time it occurs. Her leg is severely injured, and one complication leads to another–while the dog still snuffles under the floor, sometimes whining piteously, sometimes ominously silent. This sequence surely owes something to the great Spanish director Luis Bunuel, who made some of his best films in Mexico, and whose “Tristana” starred Catherine Deneuve as a beauty who loses her leg. The segment is sort of dark slapstick–morbid and ironic, as the romance is tested by the beauty’s mutilation and by the frustration (known to every pet owner) of a dog that will not come when it is called.

From time to time during the first two segments, we’ve seen a street person, bearded and weathered, accompanied by his own pack of dogs. The third segment, “El Chivo and Maru,” stars the famous Mexican actor Emilio Echevarria, who, we learn, is a revolutionary-turned-squatter and supports himself by killing for hire. El Chivo is approached by a man who wants to get rid of his partner and is inspired to add his own brutal twist to this murder scheme. The three stories have many links, the most interesting perhaps that El Chivo has rescued the wounded dog Cofi and now cares for it.

“Amores Perros” at 154 minutes is heavy on story–too heavy, some will say–and rich with character and atmosphere. It is the work of a born filmmaker, and you can sense Gonzalez Inarritu’s passion as he plunges into melodrama, coincidence, sensation and violence. His characters are not the bland, amoral totems of so much modern Hollywood violence, but people with feelings and motives. They want love, money and revenge. They not only love their dogs but desperately depend on them. And it is clear that the lower classes are better at survival than the wealthy, whose confidence comes from their possessions, not their mettle.

The movie reminded me not only of Bunuel but of two other filmmakers identified with Mexico: Arturo Ripstein and Alejandro Jodorowsky. Their works are also comfortable with the scruffy underbelly of society, and involve the dangers when jealousy is not given room to breathe. Consider Jodorowsky’s great “Santa Sangre” (1990), in which a cult of women cut off their own arms to honor a martyr. “Amores Perros” will be too much for some filmgoers, just as “Pulp Fiction” was and “Santa Sangre” certainly was, but it contains the spark of inspiration.