It has been a little more than a half-century since “It’s a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World” was first unleashed upon the public and after all that time, it still remains one of the oddest cinematic adventures in Hollywood history—a jumbo-sized comedy directed by a man known primarily for making earnest dramas about the human condition, featuring a cast jam-packed with comedy legends and produced on the kind of epic scale that was usually reserved for blockbusters such as “Ben-Hur” or “Lawrence of Arabia“. By all rational estimations, this combustible combination of elements should have resulted in total disaster, but not even the fact that it debuted only a few days before the U.S. was plunged into mourning following the assassination of President John F. Kennedy could deter it from being a huge hit at the box office in its day and a cult favorite ever since. Now Criterion has released a mammoth five-disc Blu-ray/DVD set of the film that is jammed with extras, the most significant of which is a recreation of the original 192-minute roadshow version that debuted before being cut down by more than 40 minutes, a version that had once been thought to have been lost forever (and indeed, some moments are still missing and recreated with still photographs and surviving audio tracks).

As the film opens, a car speeding through the California desert wildly passes a quartet of cars before sailing off the road and plunging down a cliff. The drivers of the four cars—neurotic dentist Melville Crump (Sid Caesar), traveling with his wife Monica (Edie Adams), hen-pecked husband J. Russell Finch (Milton Berle), trapped on the road trip from hell with sweet-natured wife Emmeline (Dorothy Provine) and monstrous mother-in-law (Ethel Merman at her Mermanest), nightclub performers Ding Bell and Benji Benjamin (Mickey Rooney and Buddy Hackett) and furniture deliveryman Lennie Pike (Jonathan Winters)—rush to help but the driver (Jimmy Durante) is moments away from kicking the bucket—literally. Before expiring, he reveals that he is noted criminal Smiler Grogan and that he has buried $350,000 in loot from a robbery 15 years earlier in a park in Santa Rosita “under a big W.” At first, the drivers put up a united front—even lying to the cops about Grogan’s final words—but when numerous attempts to figure out a way to fairly divide the possible loot fall apart due to greed, it becomes an every-man-for-himself race for the cash.

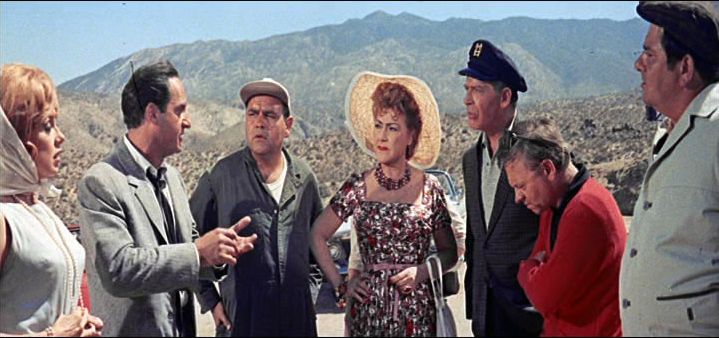

The rest of the film follows the travelers on their wild and often destructive misadventures as they attempt to reach Santa Rosita first. Along the way, they also pick up others who become embroiled in the quest for the money as well, including smarmy Brit Algernon Hawthorne (Terry-Thomas), Russell’s idiotic mamma’s-boy brother-in-law Sylvester (Dick Shawn), a couple of cabbies (Peter Falk and Eddie “Rochester” Anderson) and, most notable of all, Otto Meyer (Phil Silvers), a con man whose naked avarice would give Sgt. Bilko himself pause. What none of the players realize is that all of the chaos they are causing is being monitored by retiring Santa Rosita police chief T.G. Culpepper (Spencer Tracy), who has been trying to solve the case of the missing money for years and who finds himself succumbing to the lure of the money as well.

“It’s a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World” is essentially a symphony of slapstick—imagine a Three Stooges short writ extra-large—and one of the things about the film that raised the most eyebrows at the time was that the conductor of the barely contained chaos was none other than Stanley Kramer. At that time, Kramer was famous for producing and later directing a string of socially conscious dramas that tackled the concerns of the day in a serious and sober-minded manner—among the subjects that he grappled with were juvenile delinquency (“The Wild One”), racism (“The Defiant Ones”), nuclear war (“On the Beach”), Nazi war crimes (“Judgement at Nuremberg”) and interracial marriage (“Guess Who's Coming to Dinner“).

These films were earnest to a fault but at the time, he was one of the few filmmakers willing to deal with such topics in any capacity and while few of them made huge killings at the box-office, he quickly earned a reputation in the industry as a master of cinematic social commentary. What he did not have a reputation for, however, was being a filmmaker with any evident sense of humor. Up until then, he had only produced two films that contained any comedic elements—Richard Fleischer’s 1948 satire “So This Is New York” and “The 5000 Fingers of Dr. T”, his 1953 collaboration with Dr. Seuss—and both were notorious financial flops (though the latter would eventually go on to be rediscovered and become a cult favorite). Nevertheless, in the wake of “Judgement at Nuremberg”, he bought the rights to a one-page story treatment by William Rose and announced that he was not only going to make his next project a comedy but that it would be “the comedy to end all comedies.”

One of the chief ways that Kramer went about doing that was by cramming the film with as many comedians as the screen could possibly handle—at times, it almost feels like an old issue of “Mad” magazine with the craziness literally spilling into the margins. (Not coincidentally, one of the magazine’s most celebrated artists, Jack Davis, designed many of the posters for the film.) Besides those already mentioned, there are also brief turns by, among others and in alphabetical order, Jim Backus, Joe E. Brown, William Demarest, Andy Devine, Selma Diamond, Norman Fell, Stan Freberg, Leo Gorcey, Edward Everett Horton, Buster Keaton, Don Knotts, Zasu Pitts (in her final film appearance), Carl Reiner, Arnold Stang and The Three Stooges, not to mention unbilled cameos from additional stars like Jack Benny and Jerry Lewis.

While the cast is undeniably filled with comedy legends, very few of them, especially in the major roles, were famous as film comedians. Caesar, Berle and Silvers were among the biggest names in television at the time but had not made much of an impact on the big screen while Hackett and Winters were primarily stand-up comedians. Of the lead performers, the only ones with significant screen careers up to that point were Tracy and Rooney (who had appeared together in four previous films) but neither one was a straightforward comedic actor by any means. This isn’t necessarily a bad thing—indeed, for students of television history, seeing Caesar and Berle going toe-to-toe in their scenes together is undeniably a kick—but it does seem odd that so few film-specific performers made it into the central roles.

Thanks to the large cast and the rigors of location shooting and the elaborate set-pieces being put together—ranging from the usual car crashes and explosions to a dangerous stunt involving a plane flying through a billboard to the famous climax involving most of the cast dangling from an overloaded fire truck ladder (a sequence that featured the participation of Willis O’Brien and Marcel Delgado, the stop-motion experts behind the original “King Kong”)—the film went over-budget and by the time production was completed, it wound up costing $9.4 million, an unheard-of amount at the time for a comedy. As it turned out, Kramer’s gamble paid off and despite premiering just a few days before America went into a period of mourning following the assassination of President Kennedy, “It’s a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World” proved to be a big hit at the box office with a U.S. gross of $43.6 million, over $400 million in current dollars.

Clearly its position as a cinematic historical artifact—both as an example of practical filmmaking on a scale that would be impossible to achieve today and as a once-in-a-lifetime collection of talent—is secure but the question remains—how does it hold up today, a half-century after its initial release, simply as a movie. Well, it continues to be what it pretty much has always been—an admittedly uneven film that combines moments of absolute comedic genius with others that veer between the aimless and the off-putting. While I understand that the film is meant to be a tribute to old-school slapstick, the screenplay by William and Tania Rose could have used a little more verbal wit here and there—there is some early on (the bit in which Caesar offers up his increasingly complicated suggestions for dividing the money is a hilarious bit of double-talk) but by the second half, the dialogue mostly degenerates into people screaming at each other. As for the physical humor, it is not something that Kramer appears to be comfortable with staging. There is also a problem with pacing at times, though this may have something to do with the various last-minute edits than anything else. (Indeed, the roadshow version actually feels a little quicker even though it runs nearly 40 longer than the general release cut.)

The biggest problem with the film as a whole is that there is an occasionally nasty undercurrent to the proceedings that is sometimes off-putting. Kramer is clearly trying to demonstrate how greed can corrupt anyone but since we have barely been introduced to the characters before they begin tearing up the countryside and each other, that point is pretty much lost. One key flaw to this approach is that unless your name is Jack Benny or Daffy Duck, it is incredibly difficult to come across as both greedy and likable and since every major character—even the initially sympathetic ones played by Tracy and Provine—eventually develops an avaricious side that leads to one stupid decision after another, it is impossible to up much rooting interest in any of them.

Some of the jokes also display a sourness that is especially surprising when coming from a generally humanist filmmaker like Kramer. When the characters do damage to themselves, as when Caesar struggles to extricate himself from the hardware store basement, it is funny because they are only hurting themselves as a result of their bad behavior. However, when their actions hurt innocent bystanders—as it does from time to time—it isn’t quite as funny. In perhaps the most jarring example, an African-American couple, with all their possessions strapped to their rickety old car, is run off the road and we see them hurtle down a long slope while everything they own goes flying away. It is an ugly and dispiriting moment—more so because we are meant to just laugh it off—and it is amazing that of all the things that got cut out of the film over the years, this sequence somehow managed to survive every incarnation.

At the same time, there is no denying the fact that while it has its rough spots, “It’s a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World” still works for the most part. As a spectacle, it still has the power to dazzle audiences who have grown increasingly jaded with contemporary CGI-heavy behemoths because they know that what they are seeing is real. Fans of comedy history can still appreciate it both for gathering so much talent in one place and then putting them into unexpectedly winning combinations—Milton Berle and Terry-Thomas are surprisingly hilarious together (their extended slap-fight, in which they wind up hurting themselves more than each other, is the most successful example of pure slapstick on display) and putting Winters in a second and equally obsessive pursuit of con man Silvers also gets a lot of laughs throughout.

And so, “It’s a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World” endures—in fact, it actually holds up better today than the vast majority of Stanley Kramer’s more serious and topical dramas. Those films were daring for their time to a certain degree but they have dated quite badly and whatever impact that may have once held has been lost due to changing times. By comparison, “It’s a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World” tells a more universal tale—aside from a few technological details (much is made about the need to reach pay phones), there is nothing here that contemporary audiences would have trouble grasping. There are, after all, certain universal truths that bind us all together regardless of race, gender, age, religion or social background. One is that greed is bad and the maniacal pursuit of wealth at any cost can only lead to trouble for those who choose that path. The other—and possibly more significant—is that no matter who you are or what your circumstances may be, the sight of Ethel Merman slipping on a banana peel and landing on her hinder is and always will be inherently hilarious.

Special thanks to Michael Schlesinger for his assistance in the creation of this article.