True crime has never been bigger on television than it is now as audiences have become obsessed with shows like “Making a Murderer” and “The Jinx,” and films like “Amanda Knox” and “Casting JonBenet.” Into this “Serial”-loving genre, Netflix presents the heartbreaking “The Keepers,” a fascinating (but overlong) piece about the murder of a Baltimore nun in 1969 and the revelations that would emerge over the next five decades.

As “The Keepers” unfolds it becomes an alternating profile of evil and courage. There’s the evil of a still-unknown killer, the bottomless malevolence of an abusive chaplain, the insidious villainy of a system that appears to have covered up more than it exposed; there’s the remarkable heroism of women coming forward to report abuse, the stunning persistence of a pair of former students still looking for justice for their favorite teacher, the courage of people who are willing to look at their own family members and question their potential roles in evil. All of it adds up to a seven-hour experience that can be almost overwhelming in its degree of detail but does something a lot of true crime pieces don’t: humanizes the victims and presents them in a way you’ll never forget.

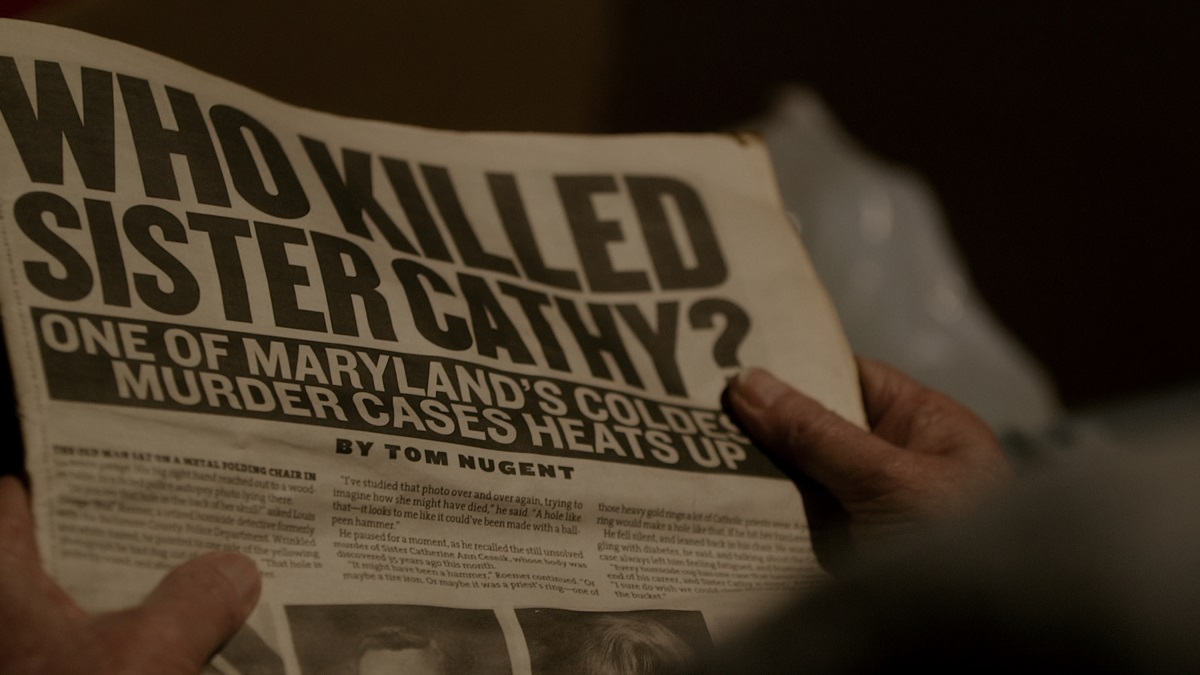

The first victim presented is Sister Cathy Cesnik, a Catholic high school teacher who disappeared on November 7, 1969. The case was truly strange right from the beginning. Her car was found with mud on the brake pedal but not gas and a twig near the steering wheel, parked illegally across the street from her apartment. She had gone out to run errands that night but never made it home. Did her boyfriend know something? Her roommate, also a nun? Someone else in the community? And then another girl went missing a few days later. Two months later, Cesnik’s body was found, but even that had its oddities including location and condition of the body. Nothing made sense, and the case went cold.

Over two decades later, it heated up. One of Sister Cathy’s former students, known in the early 1990s as “Jane Doe,” came forward with shocking stories of abuse at Baltimore’s Archbishop Keough High School in the late ‘60s. The victim alleged that the chaplain of the school not only had been abusing her but letting other community members, including doctors and police officers, rape her as well. And everyone thought that Sister Cesnik knew about it. And then there was Jane Doe’s most shocking claim—her abuser had taken her to see Cesnik’s body as a warning about what would happen to her if she spoke up. With the Jane Doe allegations dropping in the early ‘90s, the concept of “repressed memory” dominated headlines, and not just the potential truth of them as much as the worry over implanted ones. Let’s just say, no one took Jane Doe seriously enough, and the stories about her depositions, the faulty investigations, and church cover-ups will make you want to scream.

“The Keepers” introduces us to other victims of the Keough sex scandal, and for the majority of the second and third episodes you’ll hear their stories. It can be hard to take—detailed memories of rape, violation, abuse, and more, all done by powerful men to girls who looked up to them. The villain of the piece targeted girls who confessed to having been abused as children in his confessional, knowing they would be easier to victimize and that he would convince them what he was doing was God’s work. The immeasurable courage it takes for these women to come forward and reveal their stories is awe-inspiring. They’re true heroes, able to give voice to people who no longer can and inspiring enough to believe that someone who has not yet spoken up against their abuser will see this film and take that step. And you’ll also never forget Gemma Hoskins and Abbie Schaub, two of Sister Cathy’s former students who have devoted large chunks of their life to investigating the case.

Around the midway point, “The Keepers” gets even more complex in true crime terms. What if Sister Cathy knew about the abuse, but someone else killed her? Other suspects come to the front, all men, of course, and the piece reminds us how dangerous life can be for a young woman in a world of violent men. And yet director Ryan White (co-director of “The Case Against 8”) wisely returns to the heroes of his piece over and over again: the brave victims, the vigilant investigators, and, eventually, even a politician willing to take action.

There are little elements of form here and there in “The Keepers” that didn’t quite work for me—over-use of music, the overall length, some of the editing—but this is still a must-see for anyone who obsessed over “Serial” or was riveted by any of the true crime hits in the last few years. However, unlike most of those, “The Keepers” becomes less about the crime itself and more about the people impacted by it. Cathy Cesnik died 50 years ago, and it’s very likely it was because she knew about a monster—the best way to honor her memory is to hear the stories that she was never allowed to tell.