Let’s start with the big picture: As near as I can divine, Terrence Malick‘s movie “The Tree of Life” is about itself, and that statement probably sounds as confounding and imposing as viewers will find the experience (as a whole or in part) of watching it. What I mean (if I can take another flying leap at it) is that the movie expresses the drive behind its creation, somewhat like the way that “Days of Heaven” embodies the peeling and unfurling process of its own making… but, OK, not exactly. This is a movie about (and by) a guy who wants to create the universe around his own existence in an attempt to locate and/or stake out his place within it.

In other words, it’s not a modest motion picture. The ambition on display here is Tarkovskian¹ or Kubrickian in scale: think “Solaris,” “Stalker,” “The Sacrifice,” “2001: A Space Odyssey,” “Barry Lyndon” — journeys to the far reaches of space and time that are also explorations of worlds within: memories, desires, fantasies, the exercise of will and intelligence. What it comes down to, then, is that “The Tree of Life” is the story of one family (and one filmmaker) projected infinitely outward in all dimensions. (3D is so trifling, comparatively.)

The multiple narrators whispering in our ears are sometimes (but not always) identifiable as members of the O’Brien family, with the strongest voice being that of Jack (Hunter McCracken), eldest of three sons of Mr. and Mrs. O’Brien (Brad Pitt and Jessica Chastain). Jack is also played as an adult by Sean Penn. The family’s story isn’t told chronologically, but covers umpteen billion years, give or take, from the origin of the universe to the dissolution of our solar system, with most of the action taking place in Waco, Texas, in 1956 or thereabouts, when Jack is around 11. (I got some of those factoids from the press notes, some from other published material about the film. Consider them guideposts. They may or may not be literally true, and Malick isn’t particularly interested in nailing down these kinds of specifics within the film itself — including the names of all the O’Briens, some of which can be found only in the end credits. But it helps to have a few solid points of reference on hand when discussing the movie.)

I’m spending considerable time up-front here trying to suggest approaches for finding your bearings in “The Tree of Life” (although you really should see it first if you’re going to continue reading). Before describing how the movie is structured (or, at least, strung together — perhaps in some semblance of sonata form [Mr. O’Brien is an amateur pianist and fan of Toscanini’s Brahms], or perhaps closer to stream-of-consciousness) — it’s worth noting that the movie could be synopsized in any number of ways that are fairly accurate, but not mutually exclusive. One way of looking at it would be to say that it involves Jack looking back over his life (and life itself), his earliest memories to adulthood, as he attempts to reckon with the forces that shaped him — including his father, his mother, his brothers (especially the one who died)… and God, evolution, nature.

Or: “The Tree of Life” is the history of the universe in two hours and 18 minutes (though there may be a six-hour cut on the way), and it is solipsistic in the way of a child’s (or an artist’s) consciousness, conceiving of all existence as an extension of itself. That’s not necessarily a criticism, but a description of the film’s audacious endeavor. As a child, like every other child, Jack imagines himself and his family to be the center of the universe. He envisions his own actions as the cause of forces that are beyond his capacity to comprehend. And the questions he and others ask in hushed voiceover, which appear to be about the nature of God (“Where are you?” “Do you see me?” “How did I lose you?”) are perhaps more directly probing the nature of the strict, judgmental, loving, angry, pedantic, temperamental Old Testament patriarch at the dinner table²: his father, the man who speaks about himself in the third person (“Do you love your father?” he says, testing and manipulating his son) and insists his boys address him as “father” (and “sir”) — but never as “dad.” (The bible does not speak of “The Dad, the Son and the Holy Spirit.”) Not that Jack, or anyone else, is consciously likening the earthly father to the heavenly one. That’s just the way it is. Both are seemingly arbitrary and capricious creator-destroyers who work in mysterious and serpentine ways, who love and have good intentions but whose will also appears judgmental and cruel.

If the kids’ bad behavior brings down the wrath of their father (even if they don’t entirely understand what they did, or why they feel guilty, or how he can know the secret forbidden thoughts they harbor), then does God punish people the same way? The Oedipal conflict at the heart of “The Tree of Life” doesn’t just involve Jack and his tyrannical father and saintly mother (both loving, both inscrutable — sharing the same flesh and blood, but inescapably separate, Other), but the story of humankind. Like I said, it’s a movie with unbounded aspirations.

“The Tree of Life” begins with an epigraph (“Where wast thou when I laid the foundations of the earth? Job 38:4”) and a glow in the darkness — a Genesis image, perhaps, that could be cosmic or the unfocused light of a candle (or a flashlight), shaded by a human hand. (For the purposes of the movie, it doesn’t much matter which.) Soon, after a mix of ruminative, philosophical voiceovers of the sort we’ve come to expect from latter-day Malick, a telegram arrives, informing Mrs. O’Brien of the death of her son. Again, we don’t know any details, or even which son. Eventually it seems it must have been R.L. (Laramie Eppler), the one Jack seems to be closest to and the one who looks most uncannily like his father. At some point we (over-)hear that the boy was 19 years old when he died.

A man (recognizable as Sean Penn) wakes up in a house that looks like an updated, multi-leveled extension of the old Craftsman O’Brien house (thank you again, Jack Fisk). He is the adult Jack, an architect who spends much of his time wandering through towering glass-and-steel crystal structures,³ often talking to another disembodied voice (his wife? his father?) on a cell phone. He appears troubled, overcome with worry and guilt.

From the moment of the telegram’s arrival “The Tree of Life” immerses itself in the process of mourning, not just for the dead son/brother, but for the lives these people (perhaps all people) wanted to live but couldn’t, or didn’t know how to. The narrative is presented impressionistically — and, until the fragmented series of 1950s domestic scenes that dominate the middle part of the film, largely without dialog. It’s as if the characters’ words are drowned out by their grief, only partly intelligible, and in their trances they move through rooms and streets like the ghosts of silent movie actors, staggering, kneeling, grasping, caressing.

As in all of Malick’s films, the photography (this time by Emmanuel Lubezki, who also shot “The New World“) is striking, at times overwhelming, in its luminous beauty. But while the images — of faces, bodies, clothes, rooms, rivers, trees, skies, landscapes — are burnished and idealized, cleansed of extraneous elements, they’re also grounded in specific observations. Malick’s concerns are beyond verisimilitude (he’s no realist) but he wants to create places that feel inhabitable.

I found “The Tree of Life” fascinatingly inhabitable for a little under two and a half hours, but apart from what I’ve said, I can’t hazard an assessment of how or if I think it all comes together. The first time through, I was just sitting in the dark trying to get some sense of its overall shape. That may not be entirely possible… without starting over again at the beginning of time, but it’s worth a shot. I look forward to seeing it again, especially to see if I can catch a few things, perhaps insignificant, that I’m not sure I saw or heard the first time. (Even from the second row of Seattle’s Fabulous Egyptian Theater, I couldn’t make out a lot of what was spoken, on-screen or off-, the words were so deeply embedded in the sound mix.)

Some of the things I’m wondering about are just practical matters: What was Jack apologizing for on the phone to his father (“I shouldn’t have said it…”)? I know Jack shared screen space with his younger self in the desert (and with his father by the sea), but does it happen earlier, in his house or his parents’? Jack, who’s a little older than the rambunctious neighborhood boys we see him with as they go on the prowl through the alleys, throwing rocks and smashing windows, seems to feel as guilty about strapping the frog to the model rocket (“It was an experiment!”) as he does about stealing a woman’s negligee. Doesn’t Mr. O’Brien say something earlier about “an experiment”? Where does the third son disappear to for long stretches of time? Who is the kid with the burns (?) on the back of his head? When his mother tells Jack never to “do it again,” is she referring to a particular incident (shooting his brother’s finger with the air rifle? the windows? the nightgown?), or is it deliberately ambiguous? What is the name of that picture book with the serpent — the same one Linda peruses in “Days of Heaven“? What is going on when that large creature puts its foot on the smaller creature and then almost seems to stroke it? Would the six-hour version clarify some of these things? Would “Tree of Life” improve as a mini-series?

I have so many questions…

– – – – –

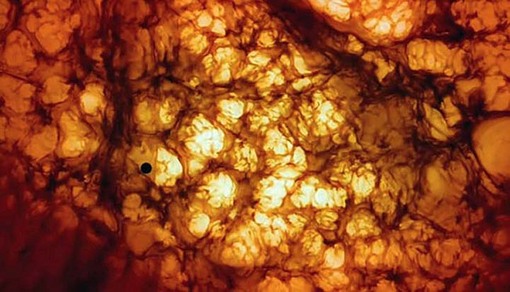

¹ I’ve seen some critics insist that one should not compare Malick movies to other films and filmmakers — or, at least, not attribute “influence” to them, because Malick ostensibly doesn’t think in those terms. And, in fact, I don’t mean to say that Tarkovsky or Kubrick directly or indirectly influenced “The Tree of Life.” But I can’t help but notice that the repeated image of the sea grass waving in the current is very much like a few shots in “Solaris” (a film about a scientist who travels to a distant planet only to come face-to-face with his own past), perhaps because it suggests the flow of life through time.

² Even some of Mrs. O’Brien’s voiceovers are ambiguous in this respect, and might also be addressed to the father of her children: “How did you come to me? In what shape, what disguise?” (She might also be talking about the serpent there.)

³ These, I later learned, were shot in downtown Houston, Texas.

Above: A shot from the opening sequence of Andrei Tarkovsky‘s “Solaris” (1972).