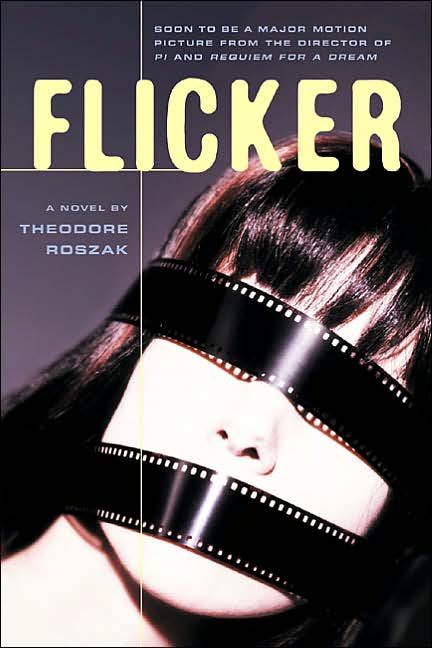

The cinema is Max Castle! At least, according to the pompous French scholar Victor Saint-Cyr in Theodore Roszak‘s spooky-satirical 1991 novel “Flicker,” which I’m now in the middle of reading. (I didn’t know when I started it, but Darren Aronovsky is reportedly working on a film version — something that’s now announced on the trade paperback cover.) Saint-Cyr proclaims that the fictitious Castle, obscure maker of seriously unclean sexploitation and horror films, “alone of all directors grasped the essential phenomenology of film. In the entire history of motion pictures, only he and Lefebvre have understood the technology so profoundly.”

In one of the funniest chapters so far, Saint-Cyr pronounces himself the founder of a new film theory he calls Neurosemiology, which in essence posits that it’s all about the flicker. The medium of cinema itself, alternating patterns of light and shadow, is a powerful form of mass hypnosis that alters the brain, quite independent of the images we think we see on the screen. One of Sant-Cyr’s students, “a bushy-haired, tautly nerved young man” named Julien, “who smoked incessantly while he spoke and never once raised his eyes,” offers an elucidation of the theory:

He seemed to be saying that in capitalist society there is an inherent tendency for the attention span of each successive generation to diminish as the experience of alienation increases, with the proletarian nervous system leading the way toward mental disintegration. New film and musical forms were pulverizing all content into tinier, more purely sensational fragments. Nothing with greater complexity than advertising copy could be understood even by privileged bourgeois youth. In movies intended for adolescent audiences, directors would soon be limiting each shot to a five-second duration at longest and then cutting back from there. […]

At the current rate of accelerating perceptual shrinkage, Julien predicted that th adolescent generation of the year 2000 would have no attention span whatsoever, hence no capacity to absorb any message longer than a single cinematic flash frame in duration. Even one-line gags and slapstick comedy would be incomprehensible to them. If, for example, they were shown a classic pie-throwing scene from the early silent films, they wouldn’t be able to recall, when the pie hit the face, where it had come from.

Ladies and gentlemen, I give you… “Speed Racer“! (And “Top Gun,” for that matter, which was released five years before “Flicker” was published, and which made Ed Wood’s movies look like masterpieces of classical storytelling continuity.)

Yes, it’s an elaborate version of the jokes (and serious arguments) people have been making ever since the birth of MTV — or, perhaps, since the opening shootout in Sam Peckinpah’s now-40-year-old “The Wild Bunch.” But look at Peckinpah’s film now: Its astonishing grace and fluidity, the masterful eye for orchestrating chaos and isolating electrifying details in what could have been just a blur of motion, are more striking than ever. And, as you can see from the Average Shot Length database at Cinemetrics, many popular films of the 21st century already average under five seconds per shot: “The Departed” (3.2 seconds), “Dreamgirls” (2.5 seconds), “Casino Royale” (2007) (3.4 seconds), “Sweeney Todd: The Demon Barber of Fleet Street” (4 seconds). On the other hand, some films have notably longer ASLs: “The Darjeeling Limited” (8.2 seconds), “There Will Be Blood” (13.5 seconds), “Paranoid Park” (16.5 seconds).

Fortunately, there’s still plenty of time to study Neurosemiology, if you speak French….