Three brothers in crisis meet in India and in desperation, in “The Darjeeling Limited,” a movie that meanders so persuasively it gets us meandering right along. It’s the new film by Wes Anderson, who after “Rushmore” and “The Royal Tenenbaums” made “The Life Aquatic with Steve Zissou“. Of that peculiar film I wrote: “My rational mind informs me that this movie doesn’t work. Yet I hear a subversive whisper: Since it does so many other things, does it have to work, too? Can’t it just exist? ‘Terminal whimsy,’ I called it on the TV show. Yes, but isn’t that better than no whimsy at all?” After a struggle with my inner whisper, I rated the movie at 2½ stars, which means, “not quite.”

I quote myself so early in this review because I feel about the same way about “The Darjeeling Limited,” with the proviso that this is a better film, warmer, more engaging, funnier and very surrounded by India, that nation of perplexing charm. The brothers, who have not been much in contact, have a reunion after one is almost killed in a motorcycle crash, and they take a journey on a train so wonderful I fear it does not really exist. (It is the fancy of the art director.)

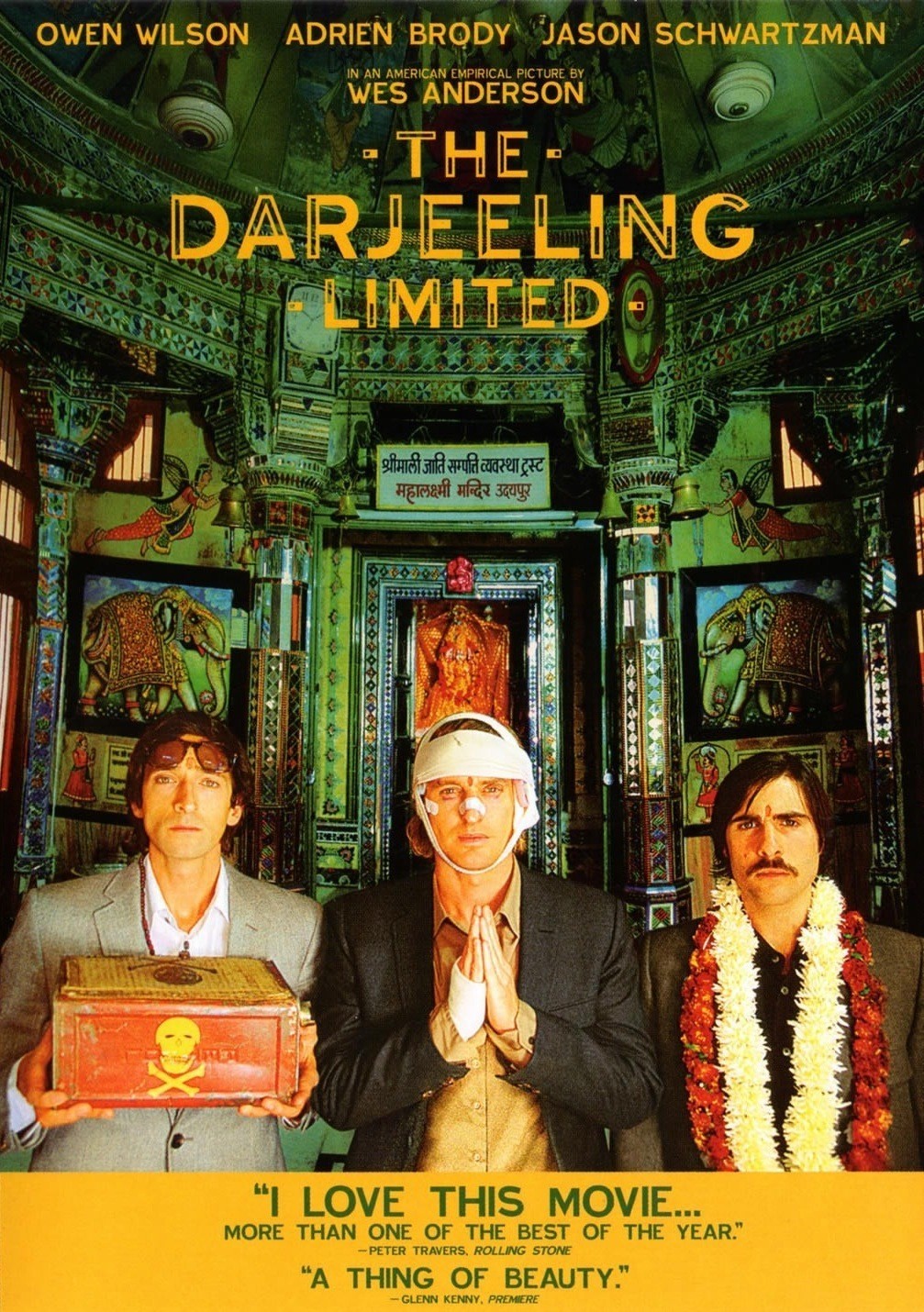

The reunion is convened by Francis (Owen Wilson), whose head bandages make him look like an outtake from “The Mummy.” Having nearly died (possibly intentionally), he now embraces life and wants to Really Get to Know his younger brothers. They are Peter (Adrien Brody), poised to divorce a wife he doesn’t love when she announces she is pregnant, and Jack (Jason Schwartzman), who dials all the way home to eavesdrop on his former girlfriend’s answering machine. “I want us to become brothers again,” Francis vows, “and to become Enlightened.”

They travel with a mountain of Louis Vuitton luggage, which means the movie will no doubt play this year’s Louis Vuitton Hawaii International Film Festival, opening Oct. 18. Francis has an assistant, Brendan (Wally Wolodarsky), whose office is next to the luggage in the baggage car, from which he issues forth a daily itinerary from the computer and printer he has brought along. The document is encased in plastic, with the laminating machine he has also brought along. Insisting on this schedule is typical of Francis; he expects without question that his brothers will comply.

Francis is the compulsive type, which is why his younger brothers find it hard to be in the same room with him. They got enough of that from their mother. He announces that their train journey of reconciliation will be enriched by visits to all the principal holy places along the way. They are also enriched by their careless purchase of obscure medications that contain little magical mystery tours of their own.

One of the film’s attractions is its Indian context; Anderson and his co-writers Schwartzman and Roman Coppola made a trip through India while they were writing the screenplay. It avoids obvious temptations to exoticism by surprising us; the stewardess on the train, for example, speaks standard English and seems American. This is Rita (Amara Karan); she comes round offering them a sweet lime drink, which is Indian enough, but later when Jack sticks his head out a train window, he sees her head sticking out, too, as she puffs on a cigarette. Soon they are in each other’s arms, not very Indian of her.

Anderson uses India not in a touristy way, but as a backdrop that is very, very there. Consider a lengthy scene where the three brothers share a table in the diner with an Indian man who is a stranger. Observe the performance of the stranger. As an Indian traveling in first class, he undoubtedly speaks English, but they do not exchange a word. He reads his paper. The brothers talk urgently and openly about intimacies and differences. He does not “react” in any obvious way. His unperturbed presence is a reaction in itself. There is a concealed level of performance: They probably know he can understand them, and he probably knows they know this. There he sits, a passive witness to their lives. It is impossible to imagine this role played any better. He raises the level of the scene to another dimension.

The casting of the three brothers is also a good fit. Their personalities jostle one another in a family sort of way; they’re replaying old tapes. Then they have unplanned adventures as a result of the obscure medications, and end up off the train and in the “real” India with all of that luggage. But Anderson doesn’t have them discover one another, which would be a cliche; instead, they burrow more deeply inside their essential natures. Then Francis springs a surprise: Their journey will end with a meeting with their mother (Anjelica Huston), who for some years has been a nun in an Indian religious order. Her appearance and behavior is our catalyst for understanding the brothers.

I said the movie meanders. It will therefore inspire reviews complaining that it doesn’t fly straight as an arrow at its target. But it doesn’t have a target, either. Why do we have to be the cops and enforce a narrow range of movie requirements? Anderson is like Dave Brubeck, who I’m listening to right now. He knows every note of the original song, but the fun and genius come in the way he noodles around. And in his movie’s cast, especially with Owen Wilson, Anderson takes advantage of champion noodlers.

If you like this movie’s whimsy and observant human comedy, there is a great Indian writer you must discover, and his name is R.K. Narayan.