“We’re Jews. We have that well of tradition to draw on, to help us understand. When we’re puzzled we have all the stories that have been handed down from people who had the same problems.”

— Mimi

“Mere surmise, sir.”

— Clive

Larry Gopnik didn’t do anything. In the whole movie he doesn’t do anything. Not much of anything, anyway. He just wants to understand what is happening to him. So, every time he protests that he didn’t do anything, he’s really asking a related question: “What did I do to deserve this?” Joel and Ethan Coen‘s “A Serious Man” is an x-ray of Larry’s life, but even the title doesn’t respect him. It’s a reference to another man, Sy Ableman (Fred Melamed), who is passive-aggressively taking over Larry’s wife life. To add insult to injury, it seems to be a fait accompli — just came at Larry out of the blue. And Larry, remember, hasn’t done anything.

Larry (Michael Stuhlbarg) lives in a Minneapolis suburb, circa 1967-70 (between “Surrealistic Pillow” and “Santana Abraxas”). It is a flat world without curbs, without fences, without boundaries. The streets and the lawns and the houses all kind of run together, and it’s hard to tell which is which. His neighbor’s mowing crosses the invisible property line, infringing on Larry’s grass. The TV antenna on the roof picks up all kinds of things out of the air, but “F-Troop” is not coming in clearly on channel 4. And Larry himself is becoming indistinct, as if he were breaking up and fuzzing out like the television picture.

“But… you… you can’t really understand the physics without understanding the math. The math tells how it really works. That’s the real thing. The stories I give you in class are just illustrative — they’re like fables, say, to help give you a picture. I mean — even I don’t understand the dead cat. The math is how it really works.”

— Larry Gopnick

The only thing i knew about “A Serious Man” going in was that it was supposedly a Coenesque take on the Book of Job, set more or less in the Minnesota of their youth. Yes and no. Upper Midwestern Kafka is more like it. But it all comes back to the box at the end of “Barton Fink.” ¹ In life, you may sometimes feel you need an explanation. Yet as Rabbi Nachtner says with an enigmatic smile: “We can’t know everything…. Hashem doesn’t owe us the answer, Larry.” And neither do the Coens.

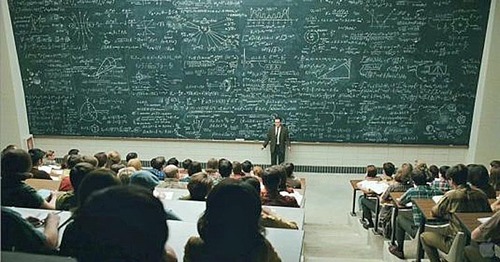

“Why does he make us feel the questions if he’s not gonna give any answers?” Larry cries. And who can blame him for asking? He’s not only a Jew, he’s also a physics professor, and he’s up for tenure. Larry is in crisis. He doesn’t merely want answers, he wants the kind of proof you can get from mathematical formulas — the math that shows how you got the answers — even if he’s demonstrating the paradox of Schrödinger’s cat or the Heisenberg uncertainty principle.

Larry has to deal with a lot of uncertainty in his life — things that can exist in more than one state simultaneously, that are significant but don’t matter, that are neither fish nor fowl, that resist being precisely delineated or measured or defined. Whether it’s his job or his marriage — or a Korean student’s grade on a particular exam — nothing in his universe is fixed or solid. As hard as he tries to pin them down, they remain in flux due to forces beyond his control. If he could get them to make sense, he could handle them. Are they signs, warnings, omens? If so, from where, and what do they mean? All our knowledge — language, science, life experience, law, stories, parables, customs, rituals, scholarship, religious faith — and what do we really know, what do we understand? Diddly.

“You can’t have it both ways!”

— Larry

“Embers isn’t the forum for legalities — you are so right! … No one is playing the “blame game,” Larry.”

— Sy Ableman

“Accept mystery.”

— Mr. Park

“Just look at the parking lot…”

— Rabbi Scott

So, an epistemological comedy as well as an existential one,² “A Serious Man” is a relentless inquiry into how we think we know what we think we know, and then asks where the knowing (or not knowing) gets us. It begins (after a fractal, Academy-ratio Yiddish folk-tale prologue with Fyvush Finkel as a Polish dybbuk — with an all-important question mark, according to the end credits) deep inside an ear canal reverberating with the sounds of Jefferson Airplane: “When the truth is found to be lies / And all the joy within you dies…” A doctor examines a man we will soon know as Larry. A boy in a Hebrew school classroom listens to a transistor radio with a white plastic earphone. We don’t know the connection between the man and the boy (are they the same person?) until later, when we learn that the kid is Larry’s son Danny (Aaron Wolf), soon to be bar mitzvahed, a boy on the verge of becoming a man (but, also, still a boy — not unlike his father).

[NOTE: I don’t want to hazard even partially revealing some resonant, essential jokes — and I’ve tried not to — but if you haven’t seen “A Serious Man,” proceed at your own risk.]

Throughout, the Coens keep us as unsteady and off-balance as Larry in his encounters with: The sometimes naked-sunbathing next-door neighbor lady with the Mezuzah, Mrs. Samsky (Amy Landecker), who startles him by entering a room though a beaded curtain, two iced teas in hand, and asking: “Do you take advantage of the new freedoms?” (She does.) Or the gruff White Hunter (and grim mower, and stern baseball catch-player) who lives on the other side. Or the pleasant, hesitant man from the tenure committee who slants in Larry’s office doorway (I can’t explain how funny his italicized posture is), always threatening to drop some terrible news, but never quite delivering it. Or Clive, the implacable Korean student who failed an exam but seems to have an instinctive (or is it cultural?) understanding of Schrödinger’s cat. Or Larry’s miserable brother Arthur (Richard Kind), who is forever in the bathroom (“Out in a minute!”), draining a sebaceous cyst on the back of his neck and scribbling an intricate, book-length mathematical manuscript he calls “the Mentaculus.” Or the multi-layered telling of the Tale of the Goy’s Teeth. Even the business practices of the Columbia Record Club become a paralyzing Kafkaesque nightmare: by doing nothing, Larry keeps ordering the (unwanted) monthly selection again and again. How can this be?

The poster image, of Larry fiddling with the aerial on his roof (yes, even with all those traditions his life is as shaky as… as a you-know-what!), comes from one of the most precarious scenes — much credit for which goes to the sound design, imagined by the Coens and realized with the invaluable expertise of longtime Coen collaborator Skip Lievsay. I’m not going to go over it here — it simply involves seeing and hearing the neighborhood from this higher vantage — but when this movie comes out on DVD I’d love to savor it shot by shot.

In the end — a moment as exquisitely timed as the breathtaking ending of “No Country for Old Men” — I choked on my own laughter and then, still smiling, felt tears coming to my eyes. I had to sit and cry a little as the credits rolled. It’s not the first Coen finish that has stunned me to tears (“Miller's Crossing,” “Fargo,” “NCFOM” — even “Barton Fink,” for the perfect beauty of the moment). I mention it not to pretend that my personal emotional response means it’s a great movie, but only because I know there are those who insist that the Coens aren’t serious, that their vision consists only of scorn and ridicule. Nothing they can do now will change those shortsighted opinions because they’re already locked in. But few filmmakers capture their (and my) view of the world³ more clearly than the Coens. In retrospect, I guess I’m not surprised it’s the movie of the year for me, the one to which I feel the deepest personal connections. It’s a magnificent piece of moviemaking, too, of course — which is why it has the impact it does.

If you want to read about the ending, there’s some detailed discussion in the comments below.

* * * *

¹ From an interview I did with Joel and Ethan Coen in 1992:

Joel: “… I mean, some people come out going, ‘I don’t get it.’ And I don’t quite know what they’re trying to ‘get,’ what they’re struggling for.”

Ethan: “It’s a weird story, but it’s a fairly straightforward story that I think can be enjoyed on its own terms… ‘Barton Fink‘ does end up telling you what’s going on to the extent that it’s important to know –you know what I mean? What isn’t crystal clear isn’t intended to become crystal clear, and it’s fine to leave it at that.”

Joel: “But we have had the reaction where people leave the movie sort of uncomfortable and befuddled because of that. Although that wasn’t our intention to do that. I was going to say that maybe our telling of the story wasn’t as clear as it should have been, but I don’t think that’s true. In terms of understanding the story, it comes across.

“The question is: Where would it get you if something that’s a little bit ambiguous in the movie is made clear? It doesn’t get you anywhere.”

² I see an ad blurb right there.

³ From a Los Angeles Times interview, October 4, 2009:

Richard Kind, the actor playing Larry’s mad-genius brother, believes the movie’s pitch-black fatalism reflects the brothers’ worldview, which prompts the following measured response:

Joel: “That’s just what we told Richard.”

Ethan: “As a world view — ” and here he pauses, agonizing over the slightest prospect of revelation, “yyyyyyyeaaaaaah. It’s an interesting story.”

Joel: “I think I even remember saying to Richard, ‘Look. This is how I view the world. So don’t mess this up.’ “