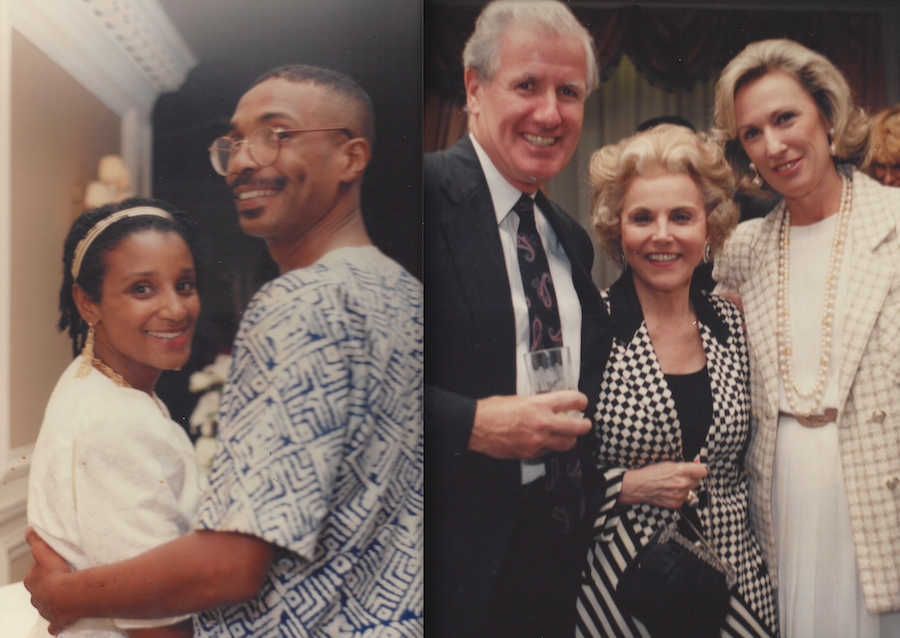

Roger and Chaz Ebert‘s wedding was held on July 18th, 1992. Here is a reprint of a blog posted by Chaz to commemorate it.

HOW DO I LOVE THEE: SONNET 43: Elizabeth Barrett Browning

How do I love thee? Let me count the ways….I love thee with the breath, smiles, tears, of all my life; and, if God choose, I shall but love thee better after death….

When I was a young girl with thoughts of romantic fancy dancing through my head, I envisioned the day when a suitor would write a poem or song dedicated to me. During our courtship, Roger wooed me with Shakespeare, often quoting from “Sonnet 18: Shall I Compare Thee To A Summer’s Day.” Then one year, my Beloved said he would do one better, and on our 20th anniversary, he surprised me with this article entitled: “ROGER LOVES CHAZ.” He excerpted it from a chapter in his memoir, “Life Itself.” It has been four years and three months since Roger passed away, but today, July 18, on what would have been our twenty-fifth anniversary, his words were once again reverberating, and so please permit me to share them with you once more. And today, I am adding a brief video that I call Joy. —Chaz Ebert

WEDNESDAY, July 18, is the 20th anniversary of our marriage. How can I begin to tell you about Chaz? She fills my horizon, she is the great fact of my life, she has my love, she saved me from the fate of living out my life alone, which is where I seemed to be heading. If my cancer had come, and it would have, and Chaz had not been there with me, I can imagine a descent into lonely decrepitude. I was very sick. I might have vegetated in hopelessness. This woman never lost her love, and when it was necessary she forced me to want to live. She was always there believing I could do it, and her love was like a wind forcing me back from the grave.

Does that sound too dramatic? You were not there. She was there every day, visiting me in the hospital whether I knew it or not, becoming an expert on my problems and medications, researching possibilities, asking questions, making calls, even giving little Christmas and Valentine’s Day baskets to my nurses, who she knew by name.

Chaz is a strong woman, sure of herself. I’d never met anyone like her. At some point in her childhood a determination must have been formed that she would make a success of herself. She was born into a large family on the West Side of Chicago, and already in high school was a tireless achiever. Her school yearbook shows her on every other page, a member of everything from the National Honor society to Spanish Club, and as vice president of the senior class to best dancer. She won a scholarship to the University of Chicago, but didn’t accept it: “What did I know? Nobody told me it was a great university. I just wanted to get out of Chicago, to go somewhere on my own.” She went to the University of Dubuque, and in keeping with the times she was a civil rights activist.

There she met her first husband, and soon they were married and raising their children Josibiah and Sonia. She might easily have called off her professional dreams and returned to Chicago, where Merle was an electrical engineer. She went to the University of Wisconsin at Madison for a BA in sociology, and then graduated from the DePaul College of Law, the alma mater of generations of Chicago politicians and lawyers. And all this time raising her family, as she and Merle moved to the suburbs and bought a home. She was a litigator at Bell, Boyd and Lloyd, an important firm. After 17 years she and Merle were divorced, but remain friends.

We like to tell people we were “introduced by Ann Landers,” which is technically true, although Eppie Lederer didn’t know her at the time. The night I took Eppie to an open AA meeting, we decided to go out to dinner together afterwards; this was the first and only time we ever had dinner for two. In the restaurant, Chaz was at a nearby table that included a couple of people I knew. I didn’t know her, but I’d seen her before and was attracted. I liked her looks, her voluptuous figure, and the way she presented herself. She took a lot of care with her appearance and her clothes never looked quickly thrown together. She seemed to be holding the attention of her table. You never get anywhere with a woman you can’t talk intelligently with.

Something possessed me to pull off one of the oldest tricks in the book. “I have a couple of friends over there I’d love for you to meet,” I told Eppie, and got up to take her across. As the introductions went around, Chaz was included. When we went back to our own table, I had her card. I studied the card and showed it to Eppie, who said, “You sly fox.”

I came back from the Toronto Film Festival with the card on my mind. I called Chaz and invited her to attend the Lyric Opera, which I’d subscribed to a year earlier because Danny Newman, the Lyric’s press agent, had stood in my office door and said, “A man like you not going go the Lyric, you should be ashamed.” Chaz, who later told me she never expected to hear from me again, said, “Actually, I’m on the women’s board of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra.” I said I loved the Symphony, but I had, cough, subscription seats at the Lyric for Monday night. The opera was “Tosca.” She said it was her favorite. “Does that scare you?” “No,” I said, “why should it?” At the time I knew nothing about “Tosca.”

We went to dinner afterwards at a restaurant in Greek Town. Something happened. She had a particular quality. She didn’t seem to be a “date” but an equal. She knew where she stood, and I found that attractive. I was going out to Los Angeles a few days later, and I asked her to come along. We formed a serious bond rather quickly. It was an understood thing. I was in love, I was serious, I was ready for my life to change. I had been on hold too long. She lived on the 82nd floor of the Hancock Center and started sending me daily e-mails, even after we’d seen each other earlier the same evening. Her love letters were poetic, idealistic and often passionate. I responded as a man and a lover. As a newspaperman, I observed she never, ever, made a copy-reading error. I saved every one of her letters along with my own, and have them encrypted on my computer, locked inside a file where I can’t reach them because the program and the operating system are now 20 years out of date. But they’re in there. I’m not about to entrust them to anyone at the Apple Genius Counter.

Our lives grew together. One day in May at the Cannes Film Festival we rented a car and drove over to San Remo in Italy to visit the grave of Edward Lear, and on the way back we stopped in Monte Carlo and in a cafe over coffee I proposed marriage. Why did I choose Monte Carlo, a place I have no desire to ever see again? I should have chosen London or Venice or for that matter Chicago. I wasn’t thinking in those terms. We were sitting there talking in a little cafe at the end of a happy day and I became overwhelmed with the desire to propose marriage. Chaz filled my mind. She excited me physically. She was funny. She made a reading of my life rather quickly, understood what I did and how I had to do it, and after I proposed marriage she resigned as a lawyer because I wanted her to travel more than she would otherwise be able to.

Chaz became the vice president of the Ebert Company. It wasn’t merely a title. She organized my contracts, protected my interests, negotiated, wheeled and dealed. I’ve never understood business and have no patience with business meetings or legal details. I had a weakness for signing things just to make them go away. She observed this, and defended me. It was a partnership.

We had times together I will always remember. Right after our first Christmas together, we flew to Venice, where I promised Chaz it would be rainy, cold, deserted, and we would have it all to ourselves. That was how I’d first seen Venice in 1966, and it was the same. It was romantic, sleeping late in the Royal Danelli and then waking up and making love and looking out across the Grand Canal. The hotel was half empty, the rooms a fraction of the summer cost. The city was shrouded in mist and always haunting. Romance in the winter in Venice is intimate and private, almost hushed. One night we went to the Municipal Casino, carefully taking only as much money as we were ready to lose, and we lost it. In a little restaurant we had enough left for spaghetti with two plates, and then lacked even the fare for the canal waterbus. We walked the long way back through the night and cold, our arms around each other, figures appearing out of the fog, lights traced on the wet stones, pausing now and again to kiss and be solemn. It was one of those experiences that seals a marriage.

At Cannes we bought a chicken sandwich for Quentin Tarantino in a beach restaurant, after “Reservoir Dogs” had been a success but he was broke. The next time we saw him at Cannes was after “Pulp Fiction,” when Miramax had rented a ballroom in the Carlton for him. It was the first time we remembered. Another night, after seeing “Boyz N the Hood” and being awed by it, we drove out of town for dinner with John Singleton, so young and filled with plans. Chaz seemed to know everybody and to remember all the names; I had often been more abstracted than anyone realized.

We had fun together. In Salvador, the capitol of Bahia in Brazil, we decided to go to a Lambada nightclub, and practiced the dance in our hotel room. Wandering around the town, we saw a dress shop with local fashions and Chaz bought a low-cut white summer gown with lots of ruffles. She looked sexy as hell when we left the hotel. When we walked into the club, an odd silence fell. Something was wrong. People seemed to be smiling for the wrong reasons. An English-speaking waitress took mercy on us, and explained the dress was a national costume intended for pageants and such. Wearing it to a nightclub was like me dressing as Uncle Sam.

In London, we stayed at 22 Jermyn Street, the former Eyrie Mansion. Chaz drew me into the contemporary art scene. I’d started collecting my Edward Lear watercolors in the 1980s, but after we moved into our town house with expanses of bare wall, we could think in terms of larger paintings. In the Purdy-Hicks Gallery on the South Bank, where we’d gone to look at work by our friend David Hiscock, we saw a spacious canvas in a store room and found ourselves side by side just regarding it. This was by Gillian Ayres, a formidable abstract expressionist who covered huge areas with bright impasto. It was a work inspired by a kite festival in India, and its energy flooded the room. Over a few years we obtained five works by Ayres, and even had dinner with her one night at the Groucho Club, where the raffish atmosphere matched her roots in London’s 1950s.

The greatest pleasure came from annual trips we made with our grandchildren Raven, Emil and Taylor, and their parents Sonia and Mark. Josibiah and his son Joseph came on one of those trips, where we made our way from Budapest to Prague, Vienna and Venice. We went with the Evans family to Hawaii, Los Angeles, London, Paris, Venice, and Stockholm. We walked the ancient pathway from Cambridge to Grantchester. Emil announced that for him there was no such thing as getting up too early, and every morning the two of us would meet in a hotel lobby and go out for long walks together. I took my camera. One morning in Budapest he asked me to take a photo of two people walking ahead of us and holding hands.

“Why?”

“Because they look happy.”

At last I could show off my city secrets. I was happy enough to drift for years lonely and solitary through strange cities, but it was more fun with the family. One quality the children had was the ability to feel at home anywhere, in restaurants, theaters, museums. They were attentive and absorbed. They had been well raised.

Those times seem more precious now that they’re in the past. I don’t walk easily anymore. When we were married I told Chaz that in 1987 I’d had a salivary tumor removed. Good Dr. Schlichter observed the surgery and told me, “They got it all. Every last speck.” But I was warned my cancer was slow-growing and sneaky, and might return years later. That’s what happened, and it set into motion all of my current troubles.

I mentioned how expert and exacting Chaz became in my care. Now I must tell you of her love. In the hospital, day after day, she was my staff of strength. In the rehabilitations she cheered me through every faltering step, and when I looked at a flight of three steps I was intended to climb, it was her will that helped me lift my feet. To visit a hospital is not pleasant. To do it hundreds of times is heroic.

The TV show was using “guest co-hosts” and Richard Roeper held down the fort. But after the first surgery failed and I nearly died, it must have been clear to her that my TV days were over. She never admitted it. She had faith, she encouraged me, her presence gave me strength. She brought my friends to see me. Studs Terkel came several times. Father Andrew Greeley was cheerful and optimistic. She brought McHugh and Mary Jo, Gregory Nava, Jon and Pamela Anderson, the mayor’s wife Maggie Daley, the actress Bonnie Hunt (who had once been an oncology nurse at Northwestern). Chaz had become friends with the healer Caroline Myss, and brought her to my bedside to evoke positive thoughts. I did not and do not believe in that kind of healing, but I see only good in the feelings it can engender. I am no longer religious, but every single day Chaz took my hand before she left and recited the 23rd Psalm and the Lord’s Prayer, and from this I took great comfort.

After I was allowed to return home for the first time, Chaz decided I was ready for the Pritikin Longevity Center near Miami. We’d been going to Pritikin, first in Santa Monica and then Florida, since before we were married, and their theories about diet and exercise became gospel to me (sometimes more in the breach than the observance). I had for years been an enthusiastic walker, but now, after rehabilitation, I was using a stroller and it was slow going.

I couldn’t eat the largely vegetarian diet at Pritikin, but Chaz knew the cooks would blend a liquid diet to supplement my cans of nutrition. She also informed me that I was going to walk, exercise, and get a lot of sunshine. Because it was painful to sit in most chairs, Pritikin found me a reclining chair that faced a big TV. I had brought along a pile of books. I cracked open the sliding doors and a fragrant breeze came in, and I would have been completely content to stay there just like that. It was not to be. Chaz ordered me on my feet for morning and afternoon walks, with my caregivers trailing along behind me with a wheelchair. I’d go as far as I thought I could, and Chaz would unfailingly pick out a farther goal to aim for. She was relentless.

In the gym everyday I cranked through 20 minutes on the treadmill and then worked out with weights and exercise bands. After the gym she took me outside to sit in the sun for half an hour. She explained how natural Vitamin D would help strengthen my bones, which were weakened during the muscular degeneration of weeks of post-surgical bed rest. I resented her unceasing encouragement. I was lazy. It was ever so much preferable to sit and read. But she was making me do the right thing.

She did it all over again after my next three tours through the Rehabilitation Institute. Four times I learned to walk again, and each time she took me to Pritikin or Rancho La Puerta in Tecate, Mexico, which I had grown to love. I parked the wheelchair for good, I was no longer using a stroller, I was walking, not quickly or for miles, but walking. And getting Vitamin D. At home, we took walks around the neighborhood and down to the Lily Pond in Lincoln Park. We began to go to all the screenings again. She found Dr. Mark Baker, an exercise therapist, to regularly work with me.

It must not have been the most pleasant thing in the world to trail along as I walked slowly. She must have wished we could still be taking our trips overseas. When she thought I was ready for it, she took me back to London and Cannes, and every autumn to the Toronto festival. I know that left on my own I would have stayed at home in my favorite Relax-the-Back chair. That I am still active, going places, moving, in good health, is directly because of her.

We planned all along to produce a show that would continue the Siskel & Ebert & Roeper tradition. Chaz did all the heavy lifting, the negotiations, the contracts. We were going to be the co-producers, but I told her she was born for the job. She repeatedly told me I needed to appear more on the show, even with my computer voice. My instinct was to guard myself. I can never be on television as I once was. She said, “yes, but people are interested in what you have to say, not in how you say it.” The point is not which of us in correct. The point is that she’s encouraging me. She has more faith in me than I do.

I sensed from the first that Chaz was the woman I would marry, and I know after 20 years that my feelings were true. She has been with me in sickness and in health, certainly far more sickness than we could have anticipated. I will be with her, strengthened by her example. She continues to make my life possible, and her presence fills me with love and a deep security. That’s what a marriage is for. Now I know. Excerpted from my memoir, “Life Itself.”

Our flower girls were Gene and Marlene’s daughters, Kate and Callie.