On July 3, 2003, a man named Doug Bruce found himself on a subway train in Coney Island with no idea of who he was or how he got there. After several days, authorities were able to establish that he was a New York stockbroker, in his early 30s, born in Britain. He was diagnosed with a rare case of retrograde amnesia.

Or maybe not. Maybe none of this is true.

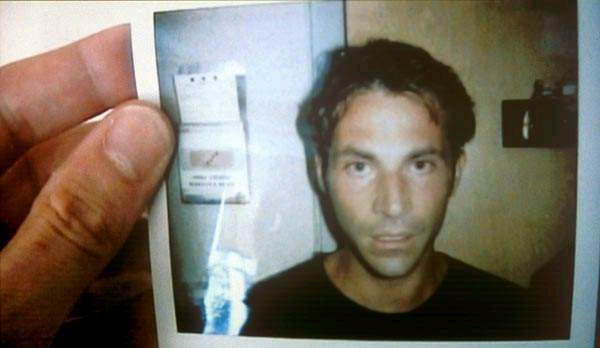

Bruce is the subject of “Unknown White Male,” a documentary that played at Sundance 2005 and is soon going into release around the country. From the day it premiered, there has been speculation that it is actually a “mockumentary,” an elaborate fraud. The charge is indignantly denied by the director Rupert Murray, who says he’d known Bruce for years and became fascinated when he heard what had happened to his friend.

Bruce’s hobby was photography, we learn, and he started keeping a video diary of his experiences that Murray was (conveniently) able to use in following his life after Coney Island. We see him being cared for by a former girl friend, meeting family and old pals in London and Spain, and falling in love with a new girlfriend who says she’s not concerned that he remembers nothing of his former life. Friends and family agree he’s a nicer guy now than he used to be.

Articles in the current GQ magazine, Variety on Feb. 16 and in the London Guardian for Feb. 20 reopen the controversy. Variety says Home Box Office considered buying the picture “but ultimately decided it was less than credible after some initial research.” Michel Gondry, whose fiction film “Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind” dealt with amnesia, told GQ magazine he didn’t think the story was authentic. But Beadie Finzi, the film’s co-producer, told the Guardian she was “outraged.” The newspaper quotes her: “He had gone through so much, been brave enough to reveal and expose himself in this documentary. And then for people to dismiss it as a fake was appalling. I felt very protective and very angry.”

All accounts point out that Bruce’s form of amnesia is diagnosed by the reputable Daniel L. Schacter, chairman of psychology at Harvard. He is indeed seen on camera. But did he diagnose Bruce, or simply describe such a condition?

I saw the film not long ago and found it dramatic and convincing. Richard Roeper and I gave it two thumbs up on our TV show, Roeper saying he wondered about its credibility. The more I thought about “Unknown White Male,” the more I also began to find it faintly fishy. There is a moment when Bruce is back home again in London, and as the car takes him past 10 Downing Street Palace he says, “Who lives there?” Amnesia or not, isn’t that a little too perfect?

The film says that after the young man was found lost and confused, news accounts of his dilemma failed to identify him. Only a phone number in his knapsack, of the mother of a woman he had dated once or twice, led to his identification.

As a newspaperman, I wondered: How could a 30-something stockbroker live and work for several years in New York in both the financial and photography worlds, disappear, have his picture appear in the papers and on TV, and not be recognized by someone?

That led me to Nexis-Lexis, a database search engine that prowls the complete texts of newspapers. I wanted to read the original news stories about Doug Bruce’s discovery in Coney Island and the search for his identity.

I couldn’t find any. Searching both American and British papers for 2003, and then for the past five years, I found no news items at all about Doug or Douglas Bruce, amnesiac, with or without the keywords Coney Island. Nor any stories about Coney Island and amnesia in 2003 without Bruce’s name. Nothing at all. Separate searches of the New York Times and London Telegraph files also failed to turn up anything. All the stories on Google and Google News deal with the movie.

Either this case was not reported at the time, although the movie says it was, or I don’t know how to use Lexis-Nexis. The second theory is a good one. Still, I think it’s fair to raise the question of the film’s authenticity, since Josh Braun, a sales rep for the film at Sundance, told Variety: “The question mark of whether it’s real or not could be a great way to direct people to see the movie. We believed it was 100% real. It seems too elaborate to keep the whole thing going. But even from the beginning, we said that an element of the marketing of the film is, ‘Is this real or isn’t it?'”

The movie opens in Chicago on March 10. I look forward to reading my review.