Amnesia has a dread fascination because it leaves its victims alive to experience the loss of self. Parents, lovers, photographs and old letters testify to the existence of a person who lived in the body whose inhabitant now regards them without recognition.

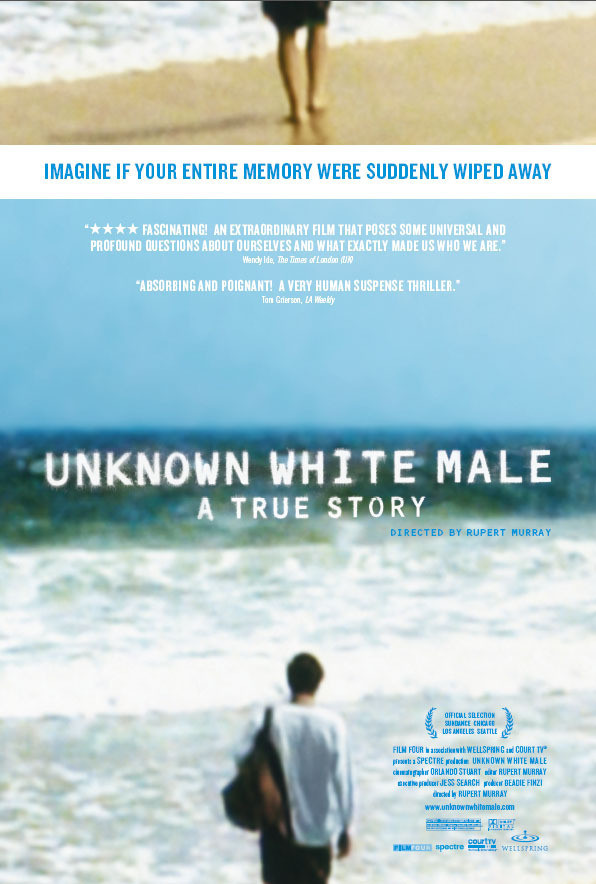

In “Unknown White Male,” that person is named Doug Bruce, or so he is told. He was raised in Britain, went to America, made money in the market, dropped out to study photography, had a girlfriend from Poland named Magda and a London pal named Rupert who is now making a documentary about him. All of this he is told, and it goes into his new collection of memories. Everything that happened to him before July 3, 2003, is gone. He is a victim of retrograde amnesia — rare, and total.

Because this documentary may be the inspiration for a fiction film, pause here for a story possibility. What if you awake from amnesia, and those around you, informing you of your earlier life, introducing themselves as parents, lovers and friends, are lying to you? What if the person you have forgotten was someone else than the person they say you were? Would it make a difference? Does it matter? If a murderer experiences amnesia, would it be ethical to execute the body that formerly harbored his memories?

Such speculations are inspired by this intriguing and disturbing film. Questions have been raised about its truthfulness; is it a fraud? I have interviewed the filmmakers and am convinced of its truthfulness, but what difference does it make? As we watch the film, Doug Bruce exists for us only in the sense that the film transfers him into our memories. Is that person any more or less real to us if the film is truthful or fraudulent?

Rupert Murray, who directed the film, has been asked why it does not contain more “proof” that it is truthful. He says it never occurred to him that anyone would doubt it, and he was more interested in the unfolding of Doug Bruce’s new life. Maybe he took the correct path after all, bypassing proof to focus on the question he begins with: “How much is our identity determined by the experiences we have? And how much is already there? Pure us?”

These questions coil around the affable face of Doug Bruce, who found himself on that July morning on a subway train in Coney Island with no idea of who he was or how he got there. A telephone number in his backpack provided a connection to a woman he had been dating, and she collected him from a hospital. There is footage taken less than a week later, as he talks about his complete loss of memory.

Rupert Murray hears what has happened to his old friend and starts making this film. Doug Bruce is introduced to Magda, his former girlfriend. They lived together for eight years. She flies back from Poland and moves in (or does she, technically, move in with a person she has never known, and who never knew her?). Bruce travels to London and Spain, and meets his parents and old friends. He does not remember them. They say he is calmer, even nicer, than the old Doug. “Given a new lease on life,” Murray tells us in his narration, “Doug seemed to be more articulate than before, more serious, more focused, as if his senses had been sharpened by a rebooting of the system.”

Gradually Bruce begins to collect a fresh set of memories. He continues his photography lessons, and his teacher says “his work has gained enormous depth.” He finds Narelle, a new girlfriend. “The longer that it goes on,” he says about his current life, “the less I care if my memory comes back.”

Yes, because if it did, would it invalidate what he now considers to be his identity? Would there be two persons inside his memory, one nicer and more focused, the other burdened with the imperfections of his previous operating system?

The thing about a movie like “Unknown White Male” is that it starts you thinking in the most unsettling ways. Rupert Murray, who claims to have met Doug Bruce in London when they were 18 or 19, has been questioned because he knows so little about Doug. If his friend was a stockbroker, what brokerage did he work for? Murray has no idea. “Quite frankly,” he told me when I raised this question, “I make films and went to art school. I didn’t know or care what firm he worked for. I’d call him up in New York, and we’d go out for a drink.” Is this plausible? Of course it is. I have friends in London of whom I could say the same thing.

How much of what we know about each other is simply a shared set of words? How much of what we know about ourselves is hearsay? When our parents tell us about our second birthday party, we no more remember that party than Bruce remembers his 30th. Yet the party goes into our database. How much is “pure us?” What Doug Bruce seems to have lost is not only his memory but even the “pure us” part — he has a different personality now. Here’s an irony: He found that he could still write his signature. But neither he nor anyone else could read it.

“Unknown White Male” is maddening at times because Murray doesn’t ask questions we’d like to shout at the screen: “Magda, if it’s not too personal … is Doug the same in bed?” “Doctor, is there a way to tell for sure if someone is faking amnesia?” “Doug, do you resent these strangers who make emotional demands because they claim they were your parents?” “Mrs. Bruce, if your son cannot remember you, does it still hurt your feelings if he doesn’t call and visit?”

This is not the review I thought I would write. I thought I would describe what is in the film, what happens and is said. But if he meets one set of people who say there were his London friends and not another, what difference does it make? We’ve never seen them before and neither has he.

The real subject of the film is Douglas Bruce sitting on two years of memories and told there is a 95 percent chance that another 30 years may return to him. A lot of people don’t want to know when they’re going to die. Maybe they wouldn’t want to be reborn, either.