It really does make sense, once you’ve overcome the novelty of the idea, that Sherlock Holmes and John H. Watson originally met while at school. Their friendship is the sort of immature bond that can best be forged between adolescents, based on Watson’s hero-worship and Holmes’ need for an admiring audience. There always has been something of the eternal teenager about Holmes and Watson, especially in their love of gadgets and mysteries and technical intricacies, and their complete bafflement when faced with such complex subjects as human nature or women.

“Young Sherlock Holmes” suggests that Holmes and Watson met in their middle teens, at an English public school, and that Holmes solved his first case at about the same time. This theory involves a rewriting of their historic first meeting, but the movie suggests that it set a pattern for many more meetings to come: Watson blunders into the orbit of the supercilious Holmes, who casually inspects him and uses a few elementary clues to tell him everything about himself.

The school they attend is one of those havens of eccentricity that have been celebrated in English fiction since time immemorial. It is run by Rathe (Anthony Higgins), a bright young man, but it is also inhabited by old professor Waxflatter (Nigel Stock), a retired don who hopes to invent the first airplane and who regularly launches unsuccessful flights from the tops of school buildings.

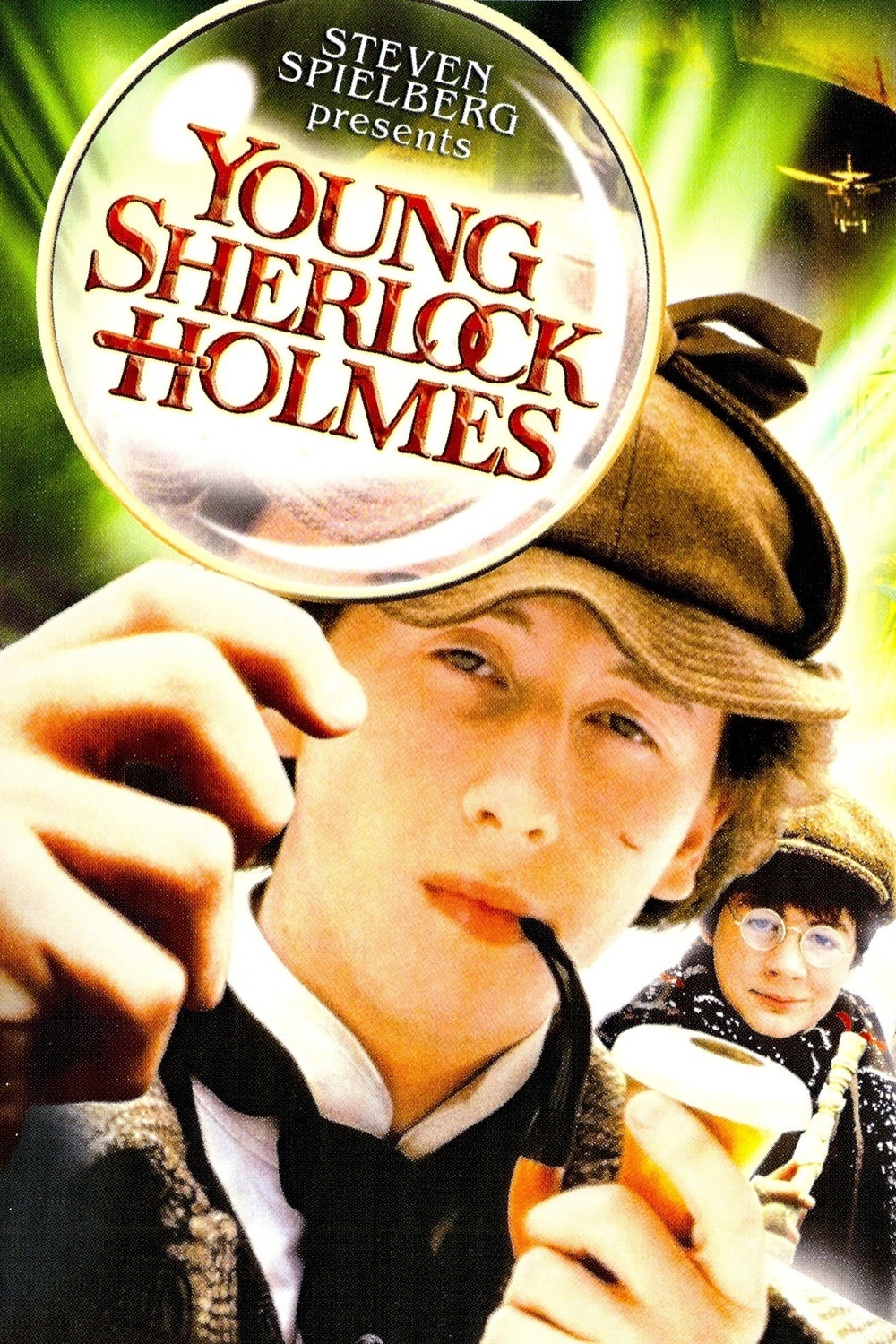

Holmes and Watson look, as schoolboys, like younger versions of the men they would someday become. Holmes (Nicholas Rowe) is tall, slender and taciturn, and Watson (Alan Cox) is short and round and nearsighted. Watson is in every sense the “new boy,” always available to run an errand for the adored Holmes, to provide a cheering section, and to chronicle the great man’s adventures.

The plot of “Young Sherlock Holmes” seems constructed out of odds and ends of several stories by Arthur Conan Doyle. For unknown reasons, several men with no apparent connection to one another die under mysterious circumstances. To Watson’s amazement, Holmes finds the missing connection, determines that they have died while hallucinating, identifies the hallucinatory drug and its means of attack, and arrives at a likely suspect.

If these story elements seem typical of Conan Doyle, there is also a lot in this movie that can be traced directly to the work of Steven Spielberg, the executive producer. The teenage heroes, for example, are not only inspired by Holmes and Watson, but are cousins of the young characters in “The Goonies.” The fascination with lighter-than-air flight leads to a closing scene that reminded me of “E.T. The Extra-Terrestrial.” And the villain’s secret temple, with its ritual of human sacrifice, was not unlike scenes in both the Indiana Jones movies.

It also doesn’t take a Sherlock Holmes to identify the one element of “Young Sherlock Holmes” that definitely doesn’t fit; that’s the character of Elizabeth, a fetching young girl played by Sophie Ward. She is the granddaughter of the mad inventor, and also lives at the school, and we are asked to believe that young Holmes has a schoolboy crush on her. I personally do not believe that Sherlock Holmes, the great investigator, ever even began to penetrate the mystery of women, but the movie just barely gets away with the character of Elizabeth by having Holmes swear there never will be another woman for him, for the rest of his life.

The elaborate special effects also seem a little out of place in a Sherlock Holmes movie, although I’m willing to forgive them because they were fun. The traditional world of Holmes (in the movies, anyway) has been limited to fogbound streets, speeding carriages, smoky sitting rooms and the homes and laboratories of suspects. In this film, we get a series of hallucinations that are represented by fancy special effects, and then there’s the pseudo-Egyptian temple of doom at the end. The effects were supplied by Industrial Light & Magic, the George Lucas brain trust, and the best one is a computer-animated stained glass window that fights a duel with Holmes.

I liked the effect, but I would have liked it more if, at the end of the movie, Holmes had drawn Watson aside, and, using a few elementary observations on the apparent movement of the stained glass, had deduced the eventual invention of computers.