Forgiveness as a core component of individual growth and communal bonding is a shared concept between the world’s big three religions, with each ideology espousing similar beliefs about the relationship between punishment and exoneration. To admit to wrongdoing is to open oneself up to criticism and judgment, and to pardon someone for a transgression against you is to extend grace. The ritual is recognizable—but its transformation into a form of reality television, and the murky questions that arise out of making absolution into entertainment, are compellingly and devastatingly considered in the film “Yalda, a Night for Forgiveness.”

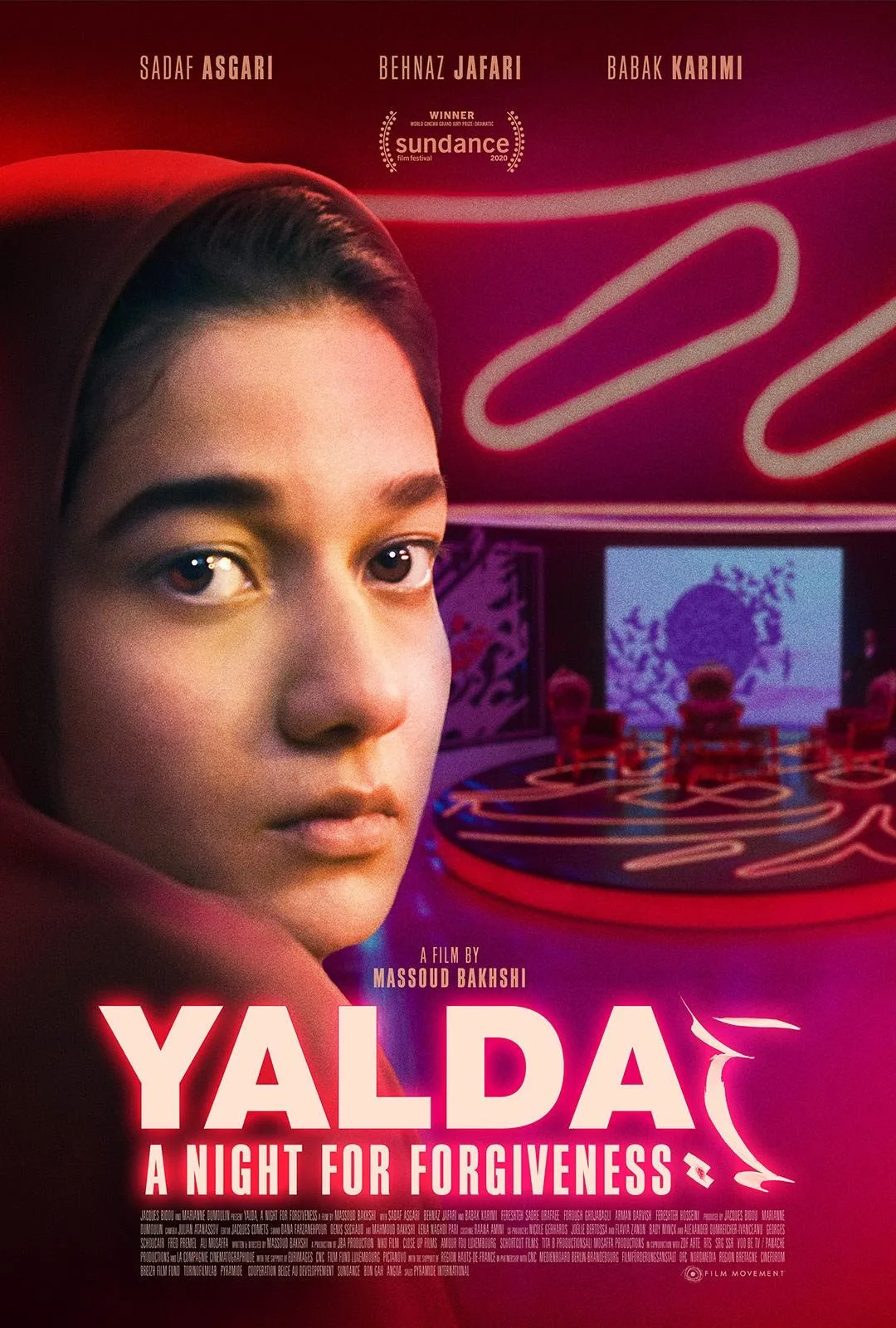

The winner of the World Cinema Grand Jury Prize: Dramatic at the 2020 Sundance Film Festival, “Yalda” unfurls like a production from Iranian filmmaker Asghar Farhadi, the two-time Oscar Best International Feature Film winner (for 2011’s “A Separation” and 2016’s “The Salesman”). Farhadi’s films are dense with details about Iranian domestic life, the myriad mazes of bureaucratic policy, and how the country’s interpretation of Islamic law impacts its judicial practices, and fellow countryman Massoud Bahkshi works with a similar combination of narrative considerations in “Yalda.” The result is a twisty-turny plot that sometimes feels like a family drama, sometimes like a legal thriller, with Bahkshi delivering a bombshell, allowing the film’s characters time to react to it, and then dropping another secret that is even more shocking than the first. It’s a tricky balancing act that requires increasingly high stakes, and in its quieter moments “Yalda” sometimes loses momentum. But the scenes during which everything clicks together are so uncomfortable and so tense that you won’t soon forget them.

Under Iranian law, the perpetrators of most violent crimes in the country face execution (“an eye for an eye”), but the judicial system also provides an opportunity for forgiveness. If the victim’s family agrees to forgive the convicted for their crime, instead of death, that person would receive reduced prison time and be responsible for paying a “price of blood” debt. This whole setup has been adapted for Iranian reality TV: For 11 years, the wildly popular show “Honey Moon” aired during the Islamic holy month of Ramadan and gathered donations from citizens—totaling in the millions—that helped pay off prisoners’ blood debts.

That system serves as Bahkshi’s inspiration for “Yalda,” in which Maryam (Sadaf Asgari), a young woman in her 20s, is strong-armed by her mother into appearing on the show “Joy of Forgiveness” on the Iranian winter solstice holiday Yalda. The widely watched “Joy of Forgiveness” is convicted murderer Maryam’s one chance to avoid being executed for the killing of her husband, a decades-older ad agency executive. If Maryam’s story resonates, she could stay alive. But she has many people to convince: not just the show’s producer, host, and control room, but also its studio audience, the 30 million viewers watching at home, and, most importantly, her husband’s only child and Maryam’s former friend Mona (Behnaz Jafari).

It is ultimately Mona’s decision whether Maryam lives or dies, and so it is imperative that Maryam secure her televised forgiveness. On a lavishly decorated TV set, surrounded by floral displays, fruit platters, and gilded furniture, Maryam tells her story, answers the host’s interrogating questions, and weathers Mona’s clear hatred. Meanwhile, backstage and in the studio’s lobby, various other individuals gather whose motivations might derail the version of events Maryam is trying to present. Whether Maryam is desperate to convince the studio audience, Mona, or herself of her innocence complicates “Yalda,” with Bahkshi crafting a world built nearly exclusively out of shades of grey.

“Yalda” is such a tightly contained film, with nearly everything occurring within the reality show’s set or at a nearby traffic stop, that a sense of claustrophobia is present from the beginning. Adding to that tension is how often the characters’ memories and explanations conflict with one another: Maryam’s mother has a different understanding of her daughter’s relationship with her husband than Maryam herself, while Maryam and Mona spar over how the former became ingratiated into the latter’s family. Baked into Bahkshi’s script is a consideration of Iranian social dynamics, and the cast’s naturalistic performances make clear the deep divisions in economic classes, in particular between Iranians who stay in the country and those who are able to leave for new lives in Europe, Canada, or the United States. The ensemble is tapping into real mistrust between certain groups of Iranian citizens and how contrastingly they view work, marriage, and family, and that wariness leaves an impression.

But all of this comes down to Asgari and Jafari, who are summarily exceptional. The point of “Yalda” is that we might never really understand why another person makes the choices they do, and the two actresses each put their own spin on that specific frustration. Asgari’s wide eyes and youthful features underscore the girlishness that makes her plight so upsetting, but the details of how her husband died are shocking to then reconcile. Jafari well conveys Mona’s standoffishness and disgust at even having to appear on the “Joy of Forgiveness,” but she also makes us feel the deep pain of losing her father. The situation in which these women find themselves is an impossible one to parse, and the power of “Yalda, a Night for Forgiveness” is in how much empathy it wrings from us while still making us complicit in their plight.

Now available in virtual cinemas.