If a picture is indeed worth a thousand words, this review would be just a selfie of yours truly looking sad and confused as the credits for “Words and Pictures” played in the background. Alas, I work in a medium driven by words, so to equal that picture, I’ve got 950 words to go.

Equating words and images is the major plot point of “Words and Pictures.” Two high school Honors program teachers oversee a student debate on which is more important, images or the written word. In the process, the teachers fall in love. It sounds like a romantic comedy with a little heft to it, until you discover that one teacher is so repellent that you root against the relationship. Adding insult to injury, the debate itself is given little screen time to develop.

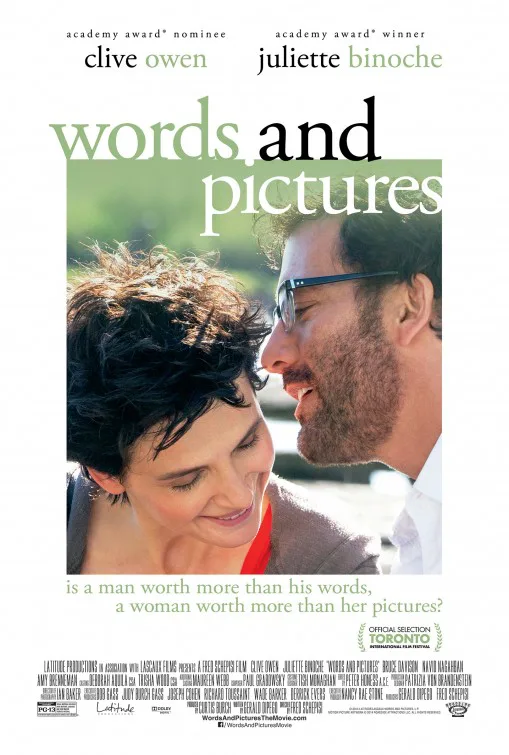

“Words and Pictures” has a helmer I greatly admire, suitably cast actors I enjoy and a plot that sounds intriguing. Rom-coms are the hardest genre to employ without failure, but director Fred Schepisi made two successful ones: “I.Q.,” which I liked, and “Roxanne,” which I adore. Clive Owen had a roguish charm in “Duplicity” and Juliette Binoche provided what little convincing romance there was to be had in “The English Patient.” As a writer whose drawing skill makes Dr. Seuss look like Frank Miller, I was all set to root for words to win the big debate.

Unfortunately, “Words and Pictures” fails at portraying both titular nouns. The screenplay by Gerald Di Pego (“Phenomenon“) is full of subpar dialogue, one-dimensional characters, scenes that belong in a different movie, other scenes that belong in the trash, multiple rom-com sins of cliché and a warped, stalkerish notion of what constitutes romance. When the hero’s idea of a term of endearment to the heroine is “you cold-hearted ice bitch,” one wonders what he’d say if he were pissed at her.

Schepisi’s direction is completely devoid of his usual style. Slant Magazine’s Ed Gonzalez aptly describes it as “unexpected point-and-shoot hackwork.” Schepisi’s camera is as disinterested in these people as we are; there must be a dozen of the same overhead shots of Binoche painting with a janitor’s mop and an equal number of shots of Owen standing around and drinking from a lime-filled liquor glass. The classroom sequences are flat and static, even when Owen is screaming at his class to startle them. Even the climactic “battle” is shot for maximum blandness, which is appropriate for the big, misguided speech that accompanies it.

Artistic professions are always used by Hollywood as psychological shorthand. Owen’s English teacher, Jack Marcus, is a published writer, which automatically makes him an arrogant drunk. This is firmly in Owen’s wheelhouse—he did a good job playing Hemingway in HBO’s “Hemingway and Gelhorn”—but unlike Papa, Jack Marcus lacks any charm whatsoever. He’s pushy, rude, mean-spirited, a bully, a potential blackmailer and a plagiarist. When a character threatens to kick him in the family jewels, you hope she does. When he goes before the school board to fight for his job after numerous drunken incidents, his knight in shining armor is his debate opponent, Miss Delsanto (Binoche).

Miss Delsanto was transferred from another school. She’s a famous, successful painter, which automatically makes her aloof and cold. She constantly demands perfection without bothering to explain how her students can achieve it. She’s artistically tormented, as all movie painters are, but at least she has a valid excuse in the rheumatoid arthritis that has robbed much of her ability to paint. Marcus antagonizes her immediately, and the refreshment of Miss Delsanto’s original dismissal gives way to the tired old cliché of falling for the scraggly-looking drunken jackass character we’re supposed to love by default.

It’s Marcus’ idea to declare “war” on Delsanto’s art class, because she favors paintings over literature. He enlists his English class, some of whom are also in Miss Delsanto’s class, to assist him in this game. The concept of words vs. pictures is poorly executed, and without this debate, there should be no movie. Yet the movie exists for long passages without once paying lip-service to this aspect of the plot.

Instead, an unnecessary subplot regarding teenage sexual harassment draws an unintentional parallel between its disturbing harassment and the relationship between Marcus and Miss Delsanto. Marcus’ star pupil, Swint (Adam DiMarco) spends every waking moment trying to hook up with Miss Delsanto’s star pupil, Emily (Valerie Tian). He does this by relentlessly badgering her, calling her names like “dim sum” and other Asian stereotypes. (Is having a White character refer to an Asians as items off a Chinese take-out menu a new trend in screenwriting? STOP IT!) When, in a very effective scene, Emily screams in frustration to leave her alone, Swint resorts to drawing a dirty picture of her, which he then uses as a cyberbullying tool.

Was this supposed to be a point “scored” for pictures? Swint’s words were just as effective at creating torment. I questioned what I supposed to glean from this, until I saw Marcus’ reaction late in the film. When Marcus’ relationship with Miss Delsantos goes off the rails, as it must in a romantic comedy, he becomes as badgering and stalkerific as Swint. I doubt this was the filmmakers’ intention, but that’s how it played.

There is one element of this film that works very well. Marcus’ alcoholism has a major effect on his relationship with his son. Their conversations will hit home for anyone who has ever lived with an alcoholic. The looks of exasperation on Marcus’ son’s face rang true—they were feelings I knew well. But as good as these few scenes are, “Words and Pictures” can’t handle the shift in tone. It’s as if the projectionist at a double feature of “Days of Wine and Roses” and “To Sir, With Love” accidentally mixed up the reels.

But what about the debate, you ask? You’ll be asking that a lot during “Words and Pictures.” The answer is not worth the wait.