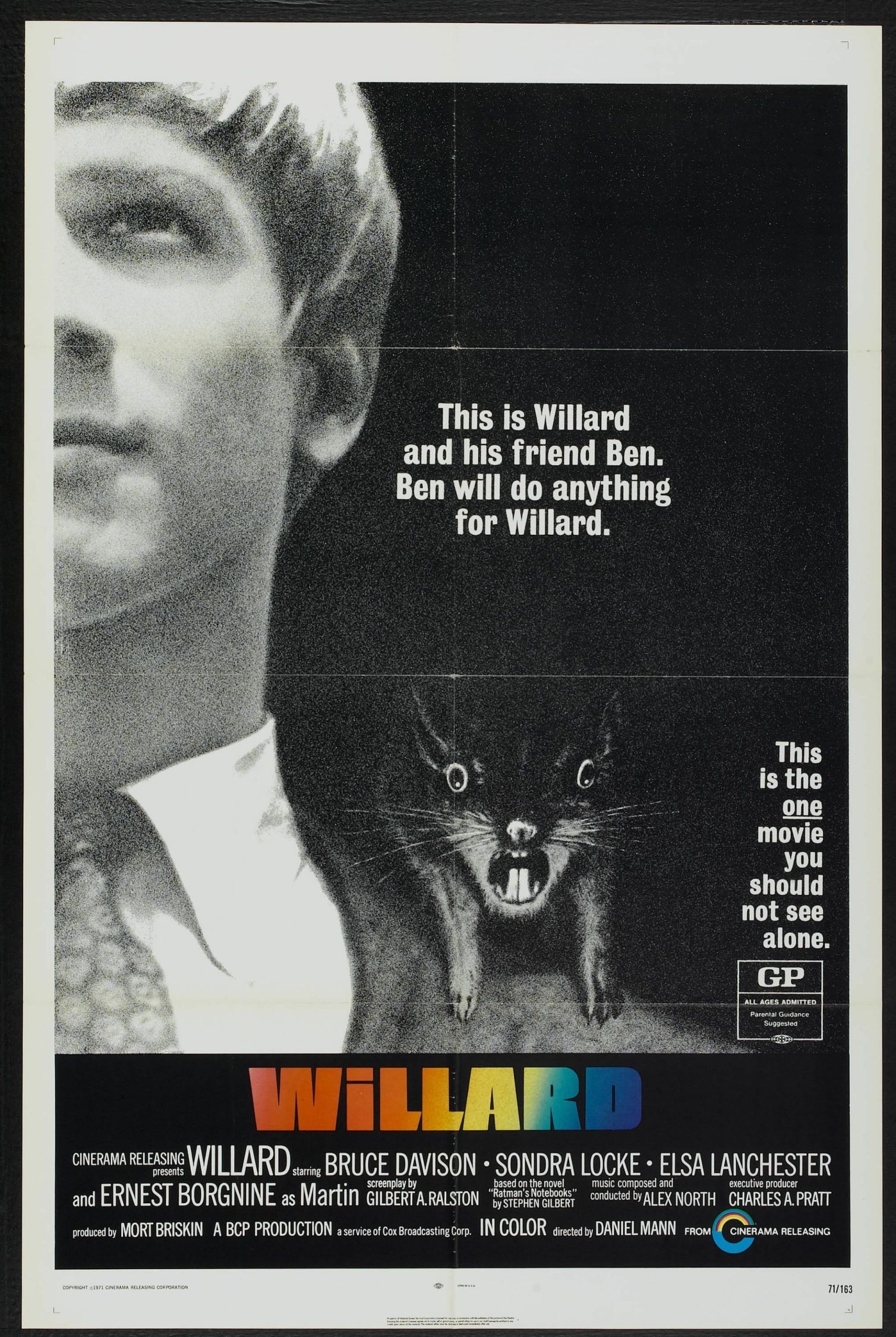

“Willard” is about rats, and about a young man who likes rats and has a mysterious ability to communicate with rats. I hate rats. I also hate spiders. I hate spiders even more than rats, although rats are more dangerous, because of my anthropomorphic bias. But more of that later.

“Willard,” as I discovered, isn’t actually about rats at all. It is a typical Horatio Alger story (“Jed the Poorhouse Boy,” if I recollect correctly, or maybe “Do and Dare, or A Brave Boy’s Fight for Fortune”), with rats playing more prominent supporting roles than they customarily did in Horatio Alger (where they were limited to run-ons).

The story concerns the plight of plucky young Willard, whose father was cheated out of the family business by the evil Mr. Martin. Willard had counted on inheriting the family concern, but now finds himself a lowly stockboy, the butt of Mr. Martin’s cruel jests. Willard and his mother inhabit the old family home, where his mother is bedridden with a disease brought on by the family reversals, and as he struggles to keep a roof over his dear old mother’s head, the heartless Mr. Martin weaves an evil scheme to foreclose on the mortgage, tear down the old homestead, and make a killing in real estate. Bad luck on this scale inevitably makes Willard broody, so imagine his delight when he discovers that he can communicate with rats. He discovers how, but we don’t. I guess you just tickle them and feed them Dog Chow and they like you.

Anyway, Willard has revenge on the evil Mr. Martin by training a bunch of rats to disrupt a garden party on the occasion of Mr. Martin’s wedding anniversary. These days, when there are so few banker’s daughters in runaway carriages, direct action seems to be the best policy. Willard’s rats bust up the party, and Willard makes special friends of two rats who get upstairs privileges and don’t have to stay in the basement. Meanwhile, his mother dies, although not of being eaten alive by rats. I wonder if they missed a bet there.

Willard’s rats reproduce and train themselves at such a furious rate that Willard eventually has more rats than he exactly needs, and he gets a little uneasy about the size of his army. One is reminded of Gandhi seeing his troops march past, and running to get at the head of them because he was, after all, their leader. The rats eventually get their opportunity to dine on Mr. Martin (exhibiting the curious ability of being able to fly through the air — almost as if they were being tossed onscreen by a prop man). And then…

But I should leave the ending to your imagination. I want to consider, instead, the sociological and psychological implications of “Willard.” What is it in this film that touches some deep-buried nerve in the public psyche? Why does wholesome family entertainment fade away, while rats make millions? I’ve thought long and deeply on this subject, believe me, and I’ve reached a conclusion at last. People have waited a long time to see Ernest Borgnine eaten alive by rats, and now that they have their chance they aren’t going to blow it.