Dr. Hunter S. Thompson is the high priest of Gonzo journalism, a reporting style in which the reporter throws himself wildly into the event he is reporting, so that in a way he becomes the event. Karl Lazlo (not his real name) was a Mexican-American attorney Thompson met in the late 1960s and immortalized in Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas, a book in which, “speaking as your attorney,” Lazlo regularly advised his client to ingest large quantities of booze, drugs and pills. The purpose: to ward off paranoia and insanity as the two engaged on a drunken odyssey through the craziness of the Vegas Strip.

The Vegas book was followed by Fear and Loathing on the Campaign Trail, in which Thompson terrorized the 1972 presidential campaign as a correspondent for Rolling Stone. His mere presence was enough to cause terror in the hearts of advance men. The last appearance – or rather disappearance – of Lazlo in Thompson’s writing is in “The Banshee Screams for Buffalo Meat,” a 1976 Rolling Stone article in which the doctor speculates that his attorney has disappeared for good and been murdered.

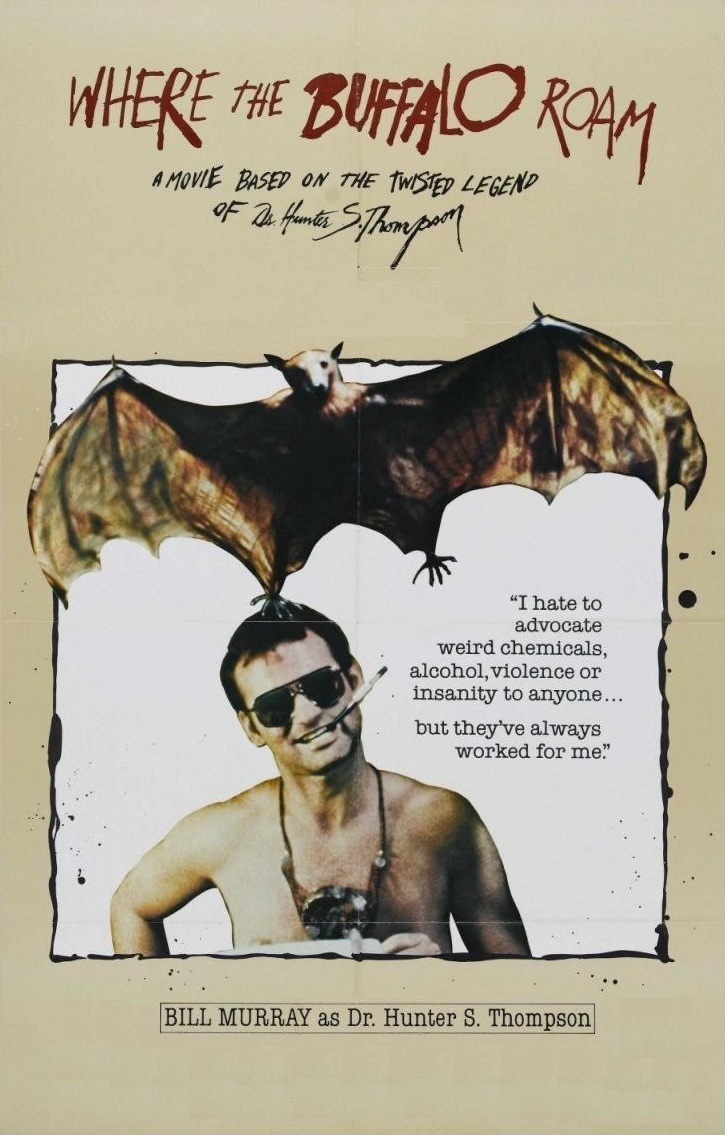

“Where the Buffalo Roam” is a comedy inspired by the relationship between Thompson (Bill Murray) and Lazlo (Peter Boyle). The credits say it’s “based on the twisted legend of Dr. Hunter S. Thompson.” The doctor has become an American folk legend not only through his increasingly infrequent and incoherent Rolling Stone articles, but also through his frequent walk-ons (as Raoul Duke) in the comic strip Doonesbury. We know his uniform: eyeshade, cigarette holder, garish Hawaiian shirt, bermuda, shorts, bottle of Wild Turkey or similar beverage.

In Doonesbury, the character fights crisis with paranoia. In real life, Thompson has proven no more immune to the effects of alcohol and drug addiction than anybody else, and lives in isolation in his cabin In Woody Creek, Colo., where he has written almost nothing worth reading since his original brilliant books. He seems to be spending these latter days of his fame having almost as much fun as Brendan Behan did.

But “Where the Buffalo Roam” is a celebration of the self-created public legend of Hunter Thompson, with no insights, or hints into the dark night of his soul. That’s a legitimate approach, and there are times during the movie when it works: There are really funny moments here, as when we learn that Thompson’s dog has been trained to go berserk at the mention of Nixon, or when Thompson covers the Super Bowl by staging a football game in his hotel suite, or when he pulls a gun on a telephone, or turns a hospital room into an orgy, or attempts to impersonate a correspondent from the Washington Post. An amazing number of these scenes are inspired by real life – although it was Sen. George McGovern, not Richard Nixon, who found himself being interviewed by Thompson while standing at a urinal.

We laugh at a lot of these moments; this is the kind of bad movie that’s almost worth seeing. But there are large things wrong with “Where the Buffalo Roam.” One of them is its depiction of the relationship between Thompson and Lazlo. That’s what the movie is supposed to be about, and yet we never discover why these two characters like one another. What is their relationship, aside from the coincidence that they happen to get stoned or drunk together in bizarre circumstances? Are they even really friends? Because the movie’s central relationship just isn’t there, the events don’t matter so much: We get bizarre episodes but no insights.

The other problem is that the Dr. Thompson character never seems to really feel the effects of the chemicals he hurls so recklessly at his system. Murray plays Thompson well but in a mostly one-level performance: He walks through the most insane situations with a quizzical monotone, a gift for understatement, a drug-induced trance. Any real person drinking and drugging like Thompson would have an occasional high, and a more than occasional disastrous low. Here he has neither.

And so the movie fails to deal convincingly with either Thompson’s addictions or with his friendship with Lazlo. It becomes just a series of set pieces, oft-told tales about the wild and crazy things he’s done while he was zonked. We wish him well, but we leave the theater wondering, a little cynically, if Thompson has had as much fun destroying himself as we’ve had watching him.