Patricia Rozema was raised as a Calvinist in Canada, and saw no films until she was 16. In this she resembles her co-religionist Paul Schrader, who saw his first film at about the same age, and went on to write “Taxi Driver” and direct “American Gigolo.” Both of the Rozema films I’ve seen deal with a young woman coming to terms with her unrealized sexual yearnings. One suspects an element of autobiography.

Rozema’s first feature was the enchanting “I've Heard the Mermaids Singing” (1987), the story of a young Toronto woman who dreams of becoming a photographer and goes to work for a sophisticated older woman who runs an art gallery. The young woman idealizes the older one but discovers secrets about her: She is a lesbian, and she is bitter about being a dealer rather than an artist. The film is ingenious in that it seems to be about the young narrator and ends up being at least as much about the woman she gets a crush on.

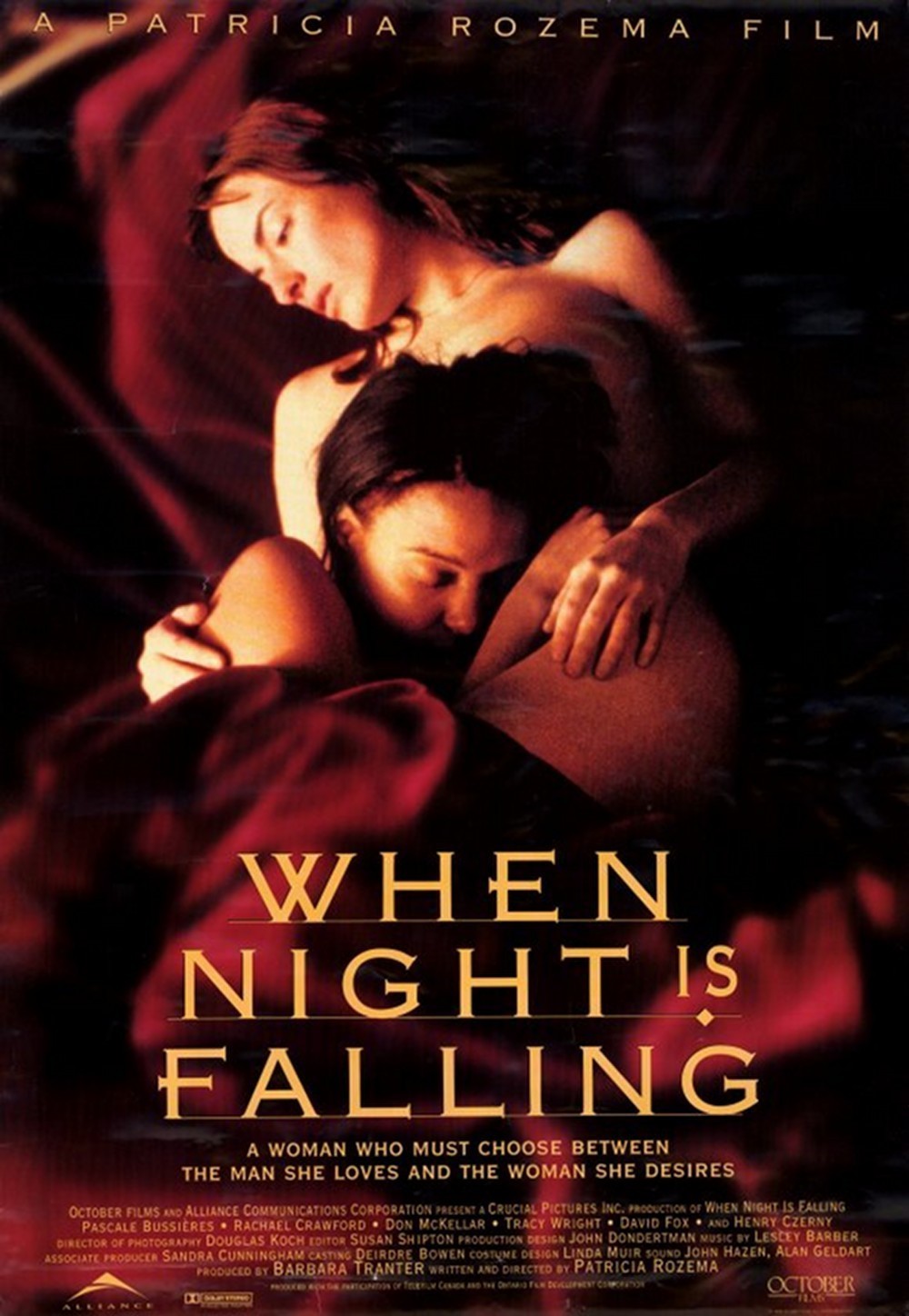

Now comes “When Night is Falling,” again about a young woman, this one a professor in a Protestant theological college in Toronto.

Her name is Camille (Pascale Bussieres), she is from Quebec, and she is engaged to marry a fellow professor named Martin (Henry Czerny).

Then one day at a laundromat she encounters a woman her age named Petra (Rachael Crawford), their laundry is exchanged – not by accident – and when Camille returns Petra’s clothes, Petra looks at her solemnly and says, “I’d love to see you in the moonlight with your head thrown back and your body on fire.” There is a part of me that responds to reckless romanticism like that, and I guess I understand Petra saying it, but before their first date? Slow down, girl! Camille is shocked and tells Petra she has made a mistake. But she hasn’t, and Camille finds herself increasingly fascinated by Petra (whose name may or may not be inspired by the heroine of “The Bitter Tears of Petra von Kant,” Fassbinder’s 1973 film about lesbianism).

The film until this point is absorbing and sensible, but then it begins to go wrong. The emotional center is sound; we believe the growing attraction the two women feel for each other, but the details of their stories seem contrived and awkward.

Petra, for example, is a little too good to be true; she is a member of a circus troupe modeled on Cirque du Soleil, and her act (not terribly difficult although she isn’t very good at it) consists of juggling balls of light in pantomime from behind a backlit screen.

She lives in a trailer decorated like an ecological hippie gift shop.

First seen in skin-tight leather (not strictly necessary since she is seen only as a shadow), she appears in a series of bizarre “artistic” costumes that hammer home the point: She is a wild free spirit, offering Camille the choice of remaining in the drab Calvinist environment, or running away and joining the circus. Does the symbolism feel just slightly strained when Camille seeks out Petra a second time, and Petra takes her on a surprise hang-gliding date? Camille’s relationship with Martin is strained and unconvincing (despite their sex scene together, they don’t seem to know each other very well). And her scenes with the Reverend DeBoer (David Fox), president of the college, are stiffly contrived. When she and Martin are offered the job of college co-chaplains, but only if they marry, she wears one of Petra’s wildly inappropriate blouses to the first interview, and stumbles through a later interview designed to test her soundness on the question of homosexuality. When DeBoer unexpectedly visits her apartment while Petra is there, Camille behaves so strangely that she seems to be concealing not lesbianism but a panic attack.

The mechanics of the story are awkward. Martin discovers the affair through a convenient photograph, and by peering through a window of Petra’s trailer. Petra sets an artificial deadline because the circus is leaving town.

The women have ludicrous misunderstandings. Oh, and there’s Bob, Camille’s beloved dog, “who I realize I love more than anyone I’m supposed to love.” Bob spends most of the movie dead in the refrigerator, and then Camille goes out into the wilderness on a dark and snowy night to bury him, meanwhile nipping at cherry brandy until she passes out and seems to freeze to death . . .

The ending of the movie completely derails. Leave out such details as that Petra is able to arrive at the side of the frozen body well before the ambulance does. Put aside problems of continuity. Forget even Bob’s remarkable reappearance in the end credits. Laughter is the friend of romance but the enemy of sexual passion (which seems funny only to the observer), and “When Night is Falling” has too many unintended laughs for its passion to be convincing. We start out nodding solemnly in sympathy with Camille and Petra. We share their angst. We care about their happiness. But then we start to snicker, and all is lost. This movie needed a strict rewrite, preferably by an unsmiling Calvinist.

I shouldn’t have left the theater worrying about what was going to happen to Bob.

Note: “When Night is Falling,” originally rated NC-17, is being released without a rating. I couldn’t find anything in the film’s sweet sex scenes to justify other than an R rating.