I have heard the mermaids singing, each to each; I do not think that they will sing to me.

– T. S. Eliot, “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock”

Don’t we all know that feeling? That feeling that other people in other places are singing in the sunshine, but here in the shadows of our own miserable existence, the parade has passed us by. It is a key discovery of adult life that almost everyone else feels the same way, too, and that anyone who believes he’s leading the parade is either stupid, mistaken or a saint.

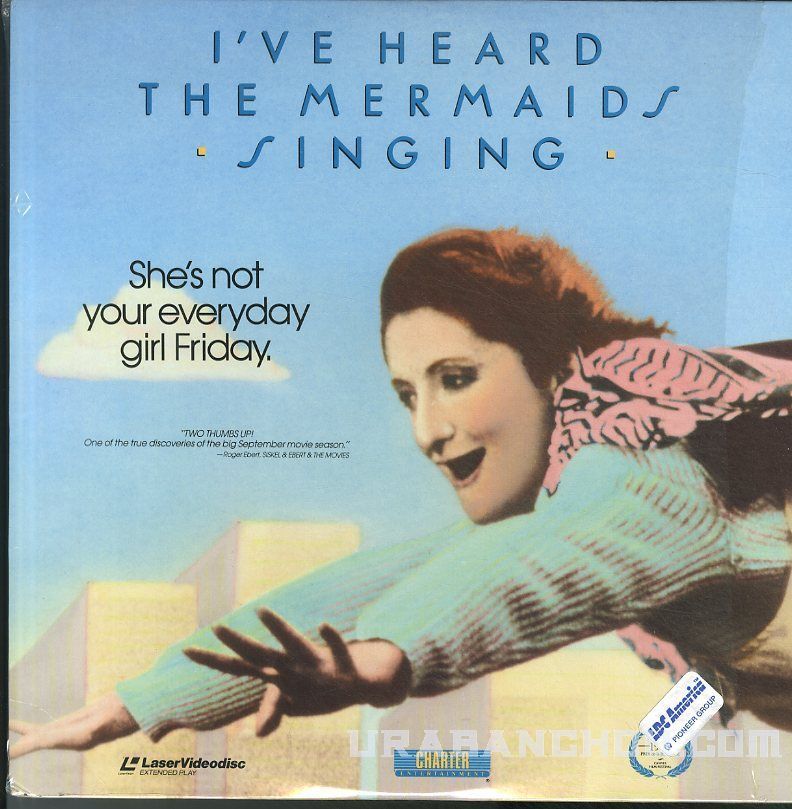

Polly (Sheila McCarthy), the heroine of “I’ve Heard the Mermaids Singing,” is a 31-year-old Toronto woman who does not think the mermaids will sing to her. The most important thing in her life is photography, and sometimes she even dreams of the pictures she will take. But no one else has seen her work, and to all outward signs she is a winsome and lonely woman with few skills. Sometimes she gets office work through a temporary agency, but she isn’t very good, and so it is with a certain amazement that she finds an employer who actually likes her.

The employer’s name is Gabrielle (Paule Baillargeon), and she is an elegant French-Canadian woman who runs an art gallery in Toronto.

Polly calls her “the Curator,” and idolizes her. The Curator is able to overlook Polly’s little lapses, such as turning letters into a sticky sea of correction fluid. And one night at a Japanese restaurant, she actually offers Polly a full-time job. Polly recalls that wonderful night, and other nights, on a homemade videotape that serves as the narration for the movie.

“I’ve Heard the Mermaids Singing” then develops into a much more subtle character study than the opening scenes might have prepared us for. Gabrielle, the Curator, reveals that her greatest regret in life is her inability to become a great painter; she sells the work of others, but she cannot paint. Polly asks to see some of her attempts, and is overwhelmed by them. But of course Polly has no confidence in her own taste, and so she smuggles one of Polly’s paintings into a show, where it is laboriously praised in impenetrable artspeak by a hilarious caricature of a critic.

If the critic has validated the Curator’s work, Polly thinks, maybe there is hope for her own photographs. So she sends them to Gabrielle anonymously, only to have them shot down as hopelessly inept.

Her spirit is crushed. But there are more discoveries for her to make.

She finds, for example, that Gabrielle has a lover, a woman named Mary, and that Mary, not Gabrielle, actually created the painting that the critic liked. It may be that the Curator lacks not only talent, but taste.

It is only gradually, while we’re watching this movie, that we realize it is as much about Gabrielle as Polly and that we are permitted to make discoveries about Gabrielle that Polly herself only dimly suspects. The movie was written and directed by Patricia Rozema, who uses a seemingly simple style to make some quiet and deep observations. What happens to Polly in the movie is easy to anticipate; she learns to trust in mermaids. What happens to Gabrielle is that she is closely observed and skillfully dissected.

When the movie is over, we leave thinking of Polly, and I have even read reviews in which the movie is treated entirely as Polly’s story. That is partly because of McCarthy’s extraordinary performance in the role; she has one of those faces that speaks volumes, and she is able to be sad without being depressing, funny without being a clown.

She strikes just the right off-center note for the narration of the film; she must not seem to sure of herself, because the movie must not seem too sure of what it wants to say. It works by indirection, and Polly is actually only the instrument for the real story here, of a lonely and proud woman whose surfaces are flawless but whose sadness is deep.

If you see this movie and then have occasion to read “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock,” which contains lines that strike some readers with the force of a blow, reflect that the narrator of the poem is more like Gabrielle than Polly. More like the Curator, who has measured out her life in coffee spoons, who has seen the moment of her greatness flicker, who lacks the strength to force the moment to its crisis, who grows old. Polly is, I suspect, intended to be out there with the mermaids, neither stupid nor mistaken, but a saint.