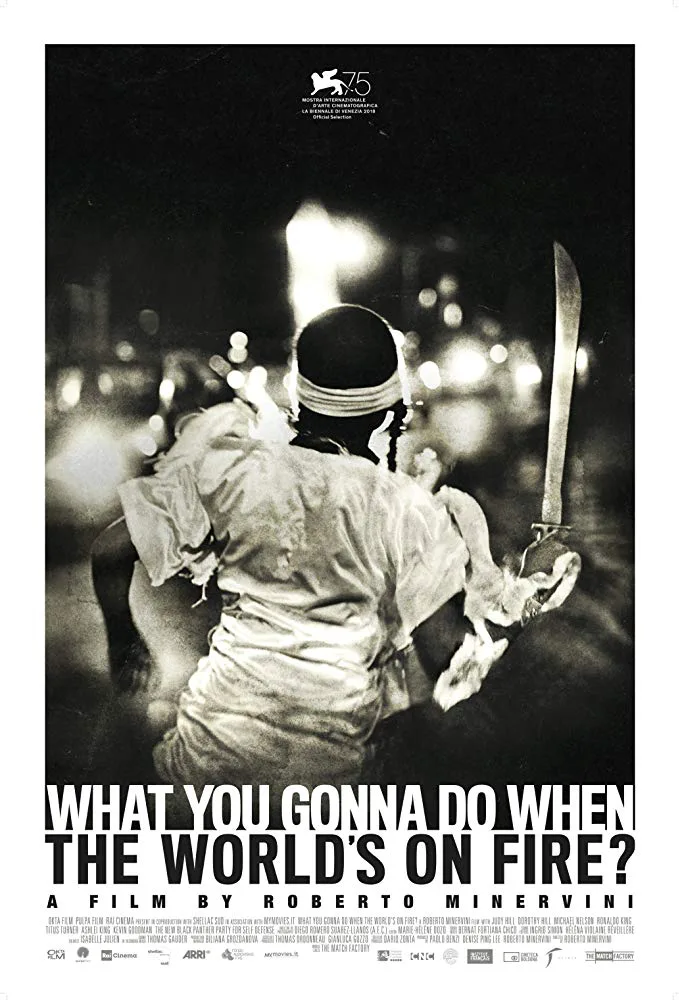

Shot with a diligent photographic discipline, Roberto Minervini’s gleaming black-and-white documentary “What You Gonna Do When the World’s on Fire?” is a rightfully fuming and attentive cinematic meditation that follows the delicate lives of a number of mostly black men and women in the American South. Investigating the ripple effects of age-old racism through four independent storylines, “World’s on Fire” is composed of countless poetic moments during which you want to freeze the frame and admire the scrupulous still in front of you. In fact, those gorgeous shots of overwhelming contrasts and use of light, realized by DP Diego Romero Suarez-Llanos, are so frequent that they make up almost the entirety of the doc’s drawn out two hours.

In that, throughout the film’s (sometimes untidy and imbalanced) segments that wrestle with topics around systemic inequality and social class, one can’t help but question Minervini’s decision to prioritize pretty photo book aesthetics over the subjects. By shooting the film in such crisp and clear monochrome, the filmmaker almost deserts the heat, grit and even urgency true colors could have infused the story with. As it is right now, there is a distancing, sterile sheen over this beautiful-to-look-at film that undercuts the director’s aspirations around establishing an intimate, you-are-there realism.

Thankfully, Minervini’s subjects couldn’t be any more captivating—the collective headstrong charisma they posses helps break down certain visceral barriers in an effortless manner. The majority of the screen time belongs to Judy; a 50-year-old native New Orleans dweller with harsh struggles in her past involving drugs. We learn that Judy got her life in order all the same (debunking the odds set against her) and opened her bar “Ooh Poo Pah Doo;” a local gathering place for both communal fun and activism. But then she lost her joint to gentrification in 2017 and started looking for other ways to make ends meet. She is outspoken, angry, self-taught and opinionated. She owns the camera (sometimes all too knowingly) and plainly charts her life journey often hindered by discrimination and ingrained class injustices.

Contrasting Judy’s self-aware, performative tendencies are Ronaldo and Titus, two brothers (14 and 9 years old respectively) of a Mississippi town, loosely bickering about life, school and their future. Raised by their protective mother who eloquently worries about their commitment to school and physical safety (a more than understandable concern, considering the police brutality that finds countless black boys in their community and beyond), the siblings make for the documentary’s most poignant and appealing narrative. There is a graceful sense of freedom in their existence as they play around train tracks and challenge their mom on her views—this independence is heartbreakingly contrasted by the idea of a future that might await them in a country where racism still runs thick in insidious ways.

We are reminded of its origins and contemporary reflection by pretty much every person who gets a meaningful amount of time on camera, but mostly by firebrand members of The New Black Panther Party for Self Defense we follow in Louisiana and Texas. Their National Chair Krystal Muhammad leads the gatherings and activism of the group, and articulately dominates most of the conversation on the commune’s goals around fighting racism. “There is no cookie cutter solution for revolution,” this segment reminds the viewer, while untangling concepts around the evolved face of white supremacy in America. “Instead of shouting ‘white power,’ they legislate and make it ‘white power,’” one member of the party articulates. The group also launches grassroots, door-to-door initiatives in support of the community’s protection against crimes committed by police forces, and often protests the killing of black youth in organized marches. Perhaps the most frustrating portion of the film, the fourth segment—about Chief Kevin and the Mardi Gras Indians of New Orleans—is sadly barely there. We witness their rituals through music and dance routines, as the story draws general parallels between the oppression of indigenous tribes and African American people in the hands of white men. Still, this fourth portion feels like a puzzling afterthought.

No stranger to stories that come from the fringes of the South with his Texas trilogy (“Low Tide,” “The Passage,” and “Stop the Pounding Heart”) as well as films like “The Other Side,” Minervini ends up only broadly engaging with the country’s shameful history of white supremacy in “World’s on Fire.” This is perhaps a direct result of his overreaching with too many subjects—all equally complex and perhaps deserving of their own standalone movie, but not evenly represented or seamlessly weaved together. At times, especially when we are in the company of the two brothers, the tone Minervini strikes is simply intoxicating in the precise ideas and feelings it captures. Other times, it is cold and meandering. In the end, “What You Gonna Do When the World’s on Fire?” feels less like a complete piece, and more like the start of something searching for its perfect form without an ideal end in sight. Considering the country’s current political landscape, it seems fitting.