The two boys live in a rural area of Georgia with their father. The older, Chris, is quietly building a reputation as a troublemaker; the younger, Tim, is an odd kid who eats mud and paint and explains he is “organizing my books by the way they smell.” Their father John mourns his dead wife and keeps his boys so isolated that on his birthday Chris complains, “We can’t even have friends. What kind of a birthday party is it with just the three of us?”

A fourth arrives. This is Deel, John’s brother, fresh out of prison and harboring resentment. “I knew your mom first — she was my girl,” he tells Chris. Deel and John’s father had a horde of Mexican gold coins with a legend attached to them: They belonged to the ferryman on the River Styx. Deel believes he should have inherited half of the coins and believes John has them hidden somewhere around the place.

If this sounds as much like a Brothers Grimm tale as a plot, that is the intention of David Gordon Green, the gifted director of “Undertow.” Still only 29, he has made three films of considerable power and has achieved what few directors ever do: After watching one of his films for a scene or two, you know who directed it. His style has been categorized as “Southern Gothic,” but that’s too narrow. I sense a poetic merging of realism and surrealism; every detail is founded on fact and accurate observation, but the effect appeals to our instinct for the mythological. This fusion is apparent when his characters say something that (a) sounds exactly as if it’s the sort of thing they would say, but (b) is like nothing anyone has ever said before. I’m thinking of lines like, “He thinks about infinity. The doctor says his brain’s not ready for it.” Or “Can I carve my name in your face?”

“Undertow,” like Green’s “George Washington” (2001) and “All the Real Girls” (2003), takes place in a South where the countryside coexists with a decaying industrial landscape. We see not the thriving parts of cities, but the desolate places they have forgotten. His central characters are usually adolescents, vibrating with sexual feelings but unsure how to express them, and with a core of decency they are not much aware of.

In writing “Undertow,” Green said at the Toronto Film Festival, he had in mind stories by the Grimms, Mark Twain and Robert Louis Stevenson, and also Capote’s In Cold Blood. He wears these sources lightly. While much is made about the family legends surrounding the gold coins, they inspire not superstition but greed, and function in the story just as any treasure would. Although we see two generations in which there is a troubled brother and a strange brother, the parallels are not underlined.

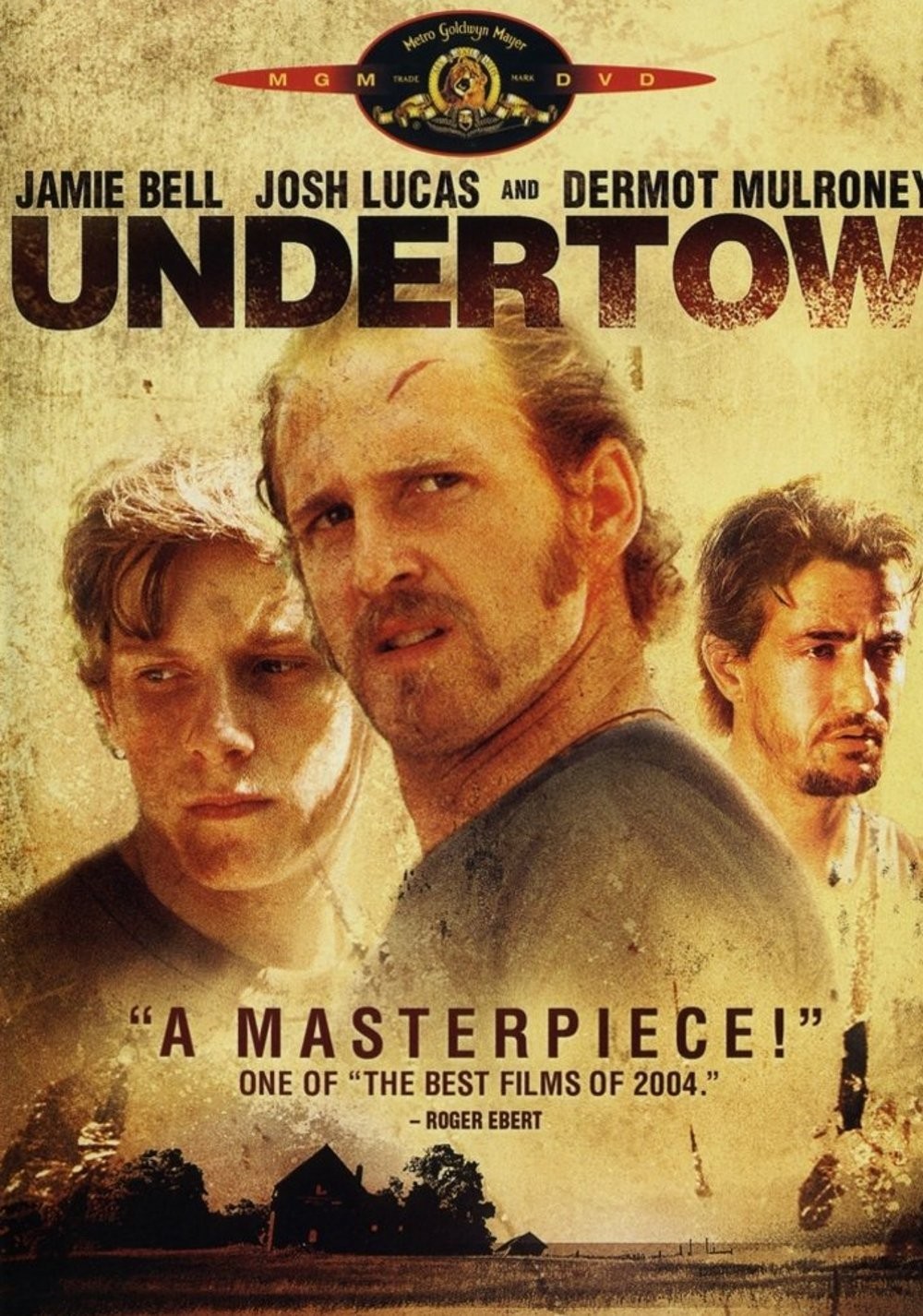

Instead, we see largely through the eyes of Chris (Jamie Bell, from “Billy Elliot” and “Nicholas Nickleby“). He figures in the startling opening sequence, where he tries to get the attention of a girl he likes, is chased away, and lands on a board with a nail in it. The audience recoils in shock. But now watch how he continues to hobble along with the board still attached to his foot. This is technically funny, but in a very painful way, and who but Green would think of the moment when an arresting cop gives Chris his board back?

Chris is in rebellion against the isolated life created for them by their father John (Dermot Mulroney). So is Tim (Devon Allen), but in an internal way, expressed by the peculiar things he eats and the chronic stomach pain that results. When their uncle Deel (Josh Lucas) appears, he is at first a welcome change, with his laid-back permissiveness. John asks Deel to watch the kids during the day while he’s at work, but Deel is not very good at this, and points his nephews toward more trouble than he saves them from.

The bad feeling over the gold coins comes to a head in an instant of violence, and the boys run away from home, entering a world that evokes “The Night of the Hunter” (1955). In both films, two siblings flee from a violent man through a haunted and dreamy Southern landscape. The people they meet during their flight all look and sound real enough, but also have the qualities of strangers encountered in fantasies: The kindly black couple who lets them work for food, and the secret community of other kids, living in a junkyard. If these passages add up to a chase scene, Green directs not for thrills but for deeper, more ominous feelings, and the music by Philip Glass doesn’t heighten, as it would during a conventional chase scene, but deepens, as if the chase is descending into ominous dreads.

Green has a visual style that is beautiful without being pretty. We never catch him photographing anything for its scenic or decorative effect. Instead, his landscapes have the kind of underlined ambiguity you’d find in the work of a serious painter; these are not trees and swamps and rivers, but Trees and Swamps and Rivers — it’s here that the parallel with “Night of the Hunter” is most visible.

“Undertow” is the closest Green has come to a conventional narrative, although at times you can sense him pulling away from narrative requirements to stay a little longer in a moment that fascinates him. He is not a director of plots so much as a director of tones, emotions and moments of truth, and there’s a sense of gathering fate even in the lighter scenes. His films remind me of “Days of Heaven,” by Terrence Malick (one of this film’s producers), in the way they are told as memories, as if all of this happened and is over with and cannot be changed; you watch a Green film not to see what will happen, but to see what did happen.

Films like “Undertow” leave some audiences unsettled, because they do not proceed predictably according to the rules. But they are immediately available to our emotions, and we fall into a kind of waking trance, as if being told a story at an age when we half-believed everything we heard. It takes us a while to get back to our baseline; Green takes us to that place where we keep feelings that we treasure, but are a little afraid of.