I saw this scene once in the London Zoo. It happened in the gloom of the insect house. Two men stood stooped over, side by side, their hands clasped behind their backs, peering through a glass into the chamber where a rare spider lived. Their faces were bathed in the low red light coming from the enclosure.

As they watched the spider, I watched them, until at last the spider did whatever it was they had been waiting for it to do. Then they stood up, looked briefly at each other, exchanged a matter-of-fact nod, and went their separate ways. London has always seemed to me to be a city of hobbyists and fanatics, experts in obscure specialties. But this moment stands out in particular, as a spider and two voyeurs shared one of the spider’s most intimate moments.

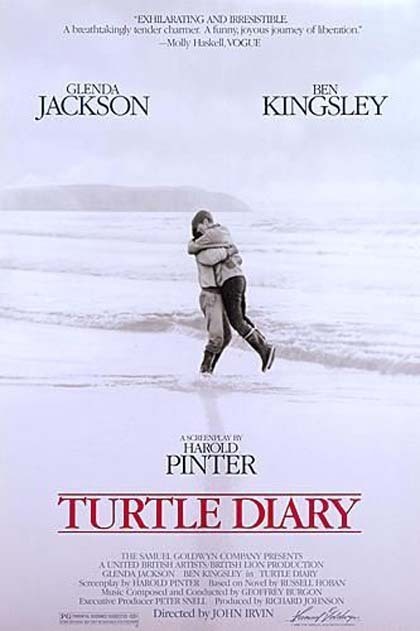

“Turtle Diary,” the quiet, sly and immensely amusing new film from a screenplay by Harold Pinter, begins with two more such devotees. They are obsessed by giant sea turtles. They peek through the glass as the turtles lazily wheel around and around their cramped space in a tank at the London Zoo. They meet again, by chance, in a bookshop way over on the other side of the city, where the man (Ben Kingsley) is a clerk, and the woman (Glenda Jackson) has come to buy a book on turtles. They gradually become aware that they are seeing each other frequently at the turtle house, and then they discover that each has approached the turtles’ keeper with the same question: What would it take to steal those giant turtles and set them free in the sea? “Turtle Diary” is about a scheme by Kingsley, Jackson and the zoo curator to do just that. But it is about a great many other things, as well. It is about the strange boarding house where Kingsley lives in company with a jolly landlady, a moody spinster and a Turk who never cleans up the kitchen after himself. It is about the flat where Jackson lives, along with her pet water beetle and a man across the landing who knows a great deal about snails. And it is about the young woman who works with Kingsley in the bookshop, and lusts after him.

In a movie filled with wonderful, small sequences, I think my favorite begins when Kingsley suddenly turns to the young woman and says, out of a clear sky, “That’s a pretty dress.” In the next scene they are in a pub, in the next scene a restaurant. And if you want to observe the mastery of screen acting, watch the way that Kingsley keeps a poker face while discussing his sex life with the woman, and then watch the way he allows himself to smile.

Ben Kingsley’s smile, so warm and mysterious, is the sun that shines all through “Turtle Diary.” This is not a predictable movie, and it does not have a predictable structure (it does not even begin to end with the climax of the turtle caper). It is about peculiar people who somewhere find the impulses to do things that make them very happy.

If this movie had been made in America, I fear it would have turned into a burlesque, with highway cops chasing turtles down the Santa Monica Freeway. “Turtle Diary” could only have been written, directed and acted in the country where I saw those two strangers wait with such infinite patience for the spider to do its thing.