There were six million family farms in 1960, but there are only two million now. That is a fact. Mary Jane Jordan saw her beloved Ethan Allen dining room table sold at auction for only $105. That is an experience. The gift of every good reporter is to turn the facts into experiences, so that we can understand what they mean and how they feel. “Troublesome Creek: A Midwestern” sees the disappearance of the family farm through the eyes of one Iowa family, the Jordans, who have been farming the same land since 1867.

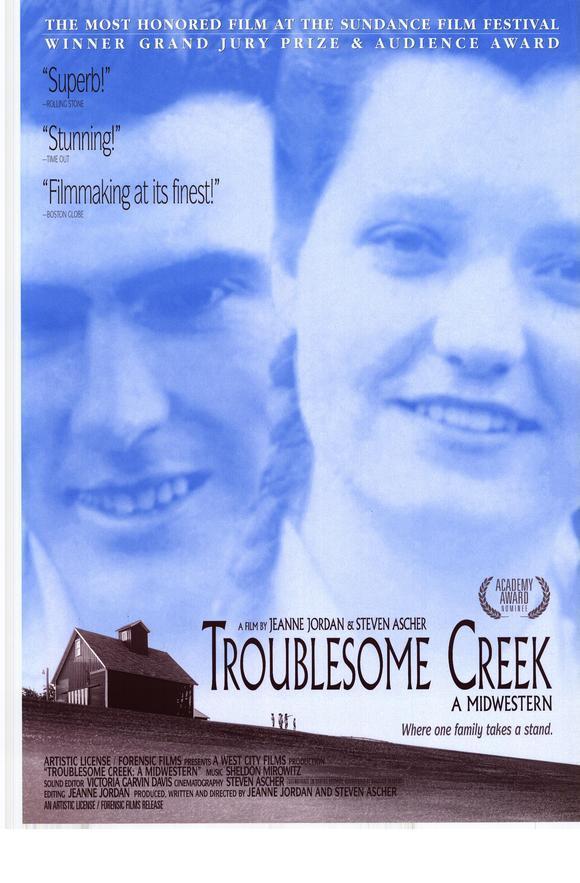

The movie is narrated by their daughter Jeanne and filmed by her husband, Steven Ascher. They co-directed it during a series of several trips back to the farm from their home in Cambridge, Mass. They present the story of her parents, Russ and Mary Jane Jordan, not as a tragedy but as a response to very hard times.

The Jordan place is what we all think of as a farm: It could be a movie set. There’s a big clapboard house, lots of well-tended outbuildings, silos, hogs, cows, and rich flat fields. Russ worries about the livestock and crops, and Mary Jane worries about the bills; we often see her on the telephone, talking to her contact at the bank about another short-term loan. The Jordans are both about 70. She was state 4-H president in high school. He once placed second in an Abe Lincoln look-alike contest.

They have a son, John, who is farming rented land nearby. “What many people fail to realize,” Jeanne explains on the soundtrack, “is that sons have to move off the farm where they were born, and work a rented farm until their father retires or dies and they can inherit the family place.” John is the obvious heir since the other Jordan children have moved into town; there isn’t a living for a big family from this land.

As the film begins, the Jordans face a crisis. Farm prices have fallen and they’ve gotten $70,000 in debt to the bank, in addition to their annual $150,000 loan. The local bank has been absorbed into a megabank named Norwest, which has a tower in Des Moines from which tidy young men telephone with news of “risk ratios.” It is unlikely the Jordans can get more credit.

We see flashbacks to better days, and photographs of all the Jordans who have worked this land, including the great-great-grandfather who came out to Iowa from Ohio after the Civil War. During a visit home, Jeanne and her husband join her parents in visiting the farm where she was raised–the rented farm her father worked while waiting for *his* father to retire. “When I was a child I didn’t even know we rented this farm,” she says. “I thought of it as home.” The clothesline trees are still in the yard and a closet door still shows signs of an unwise orange paint job, but the farm is abandoned. “I wouldn’t think a place could go down this bad in 15 years,” says Russ.

He looks a little like Gary Cooper. Mary Jane could pose for Bisquick commercials. They like to watch Westerns on TV, and their daughter casts their story as a “midwestern,” a last stand by heroic figures against the onslaught of the bankers.

Then more bad news arrives; The farm John rents is being sold. He owns equipment, but has no place to use it. Russ devises a plan. He and his wife will sell everything–their livestock, farm machinery, house, possessions, everything–to pay off the bank debt and keep the land. They’ll move to town (they know a little house that’s walking distance from Van’s Chat and Chew) and John will work the land with his machinery.

The film follows the preparations for the big auction sale with details that will be familiar to many who have never been on a farm. Mary Jane cannot bring herself to part with certain items–a plant stand, her collections of saucers and spoons–but she believes fondly that her treasured Ethan Allen dining room set, protected from scratches all these years with pads, will get a good price. I remember my mother speculating about the untold fortune she was convinced her Hummel figurines would bring.

The table goes for almost nothing. Mary Jane bites her lip in disbelief. But the plan keeps the wolf from the door for the time being, and John takes up the struggle of all the Jordans before him.

The underlying lesson is clear: Our state and federal farm policies do not really allow for family farms anymore. Corporations and conglomerates now farm the land, with men paid by the day or the week. Big banks don’t much care. Small banks are sold to big banks. When Russ calls up Des Moines to tell the bankers he can pay off the loan, he says they’re happy to hear the good news. “Daddy, that’s just guilt!” his daughter tells him. “You don’t have to make it so easy for them!” In Gary Sinise’s “Miles from Home” (1988), Richard Gere and Kevin Anderson starred as two brothers unable to make a go of their family’s Iowa farm, which had been visited by Khrushchev as the “farm of the year” in 1959. Filled with drama and action, it was a pretty good film. Now here is the everyday face of the same story. Should we make it easier for family farms? Yes. Why? Because they represent something we think America stands for. Strange how for all the talk of individualism and resourcefulness from politicians, our country drifts every year closer to a totalitarianism of the corporation.