“Miles from Home” opens with what looks like old TV news footage, in snowy black and white, of big Cadillacs speeding down dusty roads past prosperous cornfields. Then we see the stocky man in the oversize suit climbing out of the limo, and we remember the event: This is the famous visit that Nikita Khrushchev paid to an average American farm in Iowa. On the front porch steps, he shakes hands with the farmer, while the farmer’s two small boys stand uneasily at attention, their hair slicked down flat with brilliantine.

That was 30 years ago. Now, as the film turns into color, a fierce rain storm is sweeping the plains, and the farmer’s two sons, grown to men, struggle to move a big combine before it gets stuck in the mud. The brothers are named Frank and Terry Roberts, and in the summer of 1987 they have a weather problem; ironically, in view of the drought of 1988, it is too much rainfall. Their corn is soaked and some of it is rotting. Their yield will be disappointing. On the walls of the farmhouse where they were born are plaques and clippings naming their father the Farmer of the Year. But this is not the first bad year the sons have have had, and they will lose the farm to the bank.

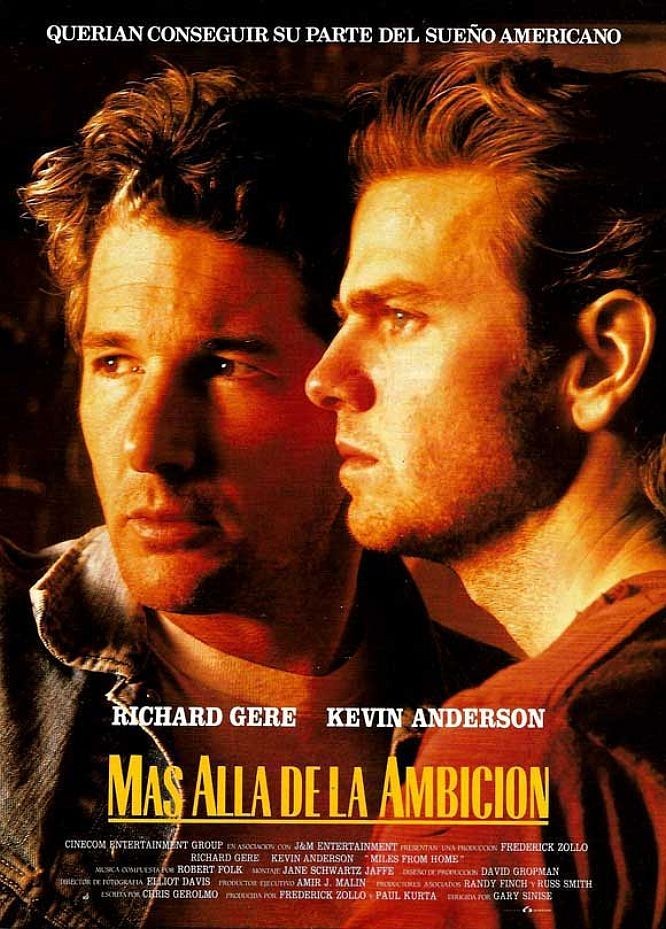

Those are the opening scenes of “Miles from Home,” a movie about the farm crisis that is sometimes too contrived, but finally very moving as the story of an angry reaction to the squeeze on small farmers. The movie stars Richard Gere as the older, angrier brother, and Kevin Anderson as the younger, sweeter kid who is carried along by Gere’s headlong rage.

There is a quiet scene near the beginning of the film that sets up a lot of things. The brothers are holding a yard sale to raise some cash. A thoughtless, pretty city girl (Penelope Ann Miller) stops by with a girlfriend, and observes to Anderson, “People would have to be pretty desperate to try to sell junk like this.” Then she realizes it is Anderson’s farm. Her eyes fill with tears as she starts to apologize, but then there is a charged silence between the two of them, as they realize they have fallen in love.

All right, so love at first sight is contrived and corny, an obvious plot device. Plots are as good as the actors who inhabit them, however, and Anderson and Miller create a believable, warm chemistry here, one that will serve as the film’s center when the Gere character flies out of control. That happens slowly, implacably, as Gere realizes he has failed the memory of his father and lost the farm. He blames himself, and there is a scene in a cemetery, Gere talking to his father’s tombstone, before the furies inside of him break loose.

In an action that mirrors one of the key scenes in “Bonnie and Clyde,” he shoots out some of the windows of the farmhouse. Then he intimidates his kid brother to join him in a wilder plan: to burn down the farmhouse and set the fields ablaze rather than see the farm fall into the hands of the bank. With the flames roaring against the sky, the two brothers set off on a doomed escape across the state of Iowa, where the symbolism of their act makes them folk heroes.

Many of the visuals in “Miles from Home” seem to echo compositions in Terrence Malick’s “Days of Heaven” (1978), one of Gere’s earliest films. But the story of the two fugitives becoming media heroes is a reminder of both “Bonnie and Clyde” and Malick’s own earlier film, “Badlands,” with Martin Sheen and Sissy Spacek on the run. That film began with a murder; this one seems doomed at times to lead to one.

As Gere and Anderson use a series of stolen cars to move across the state, they meet a series of strange people – outsiders and rebels – who support them. They include a roadhouse stripper (Laurie Metcalf), an entranced woman in a trailer park (Judith Ivey) and a lean reporter who wants to tell their story (John Malkovich). And there are all the people in the beer tent at a county fair who know exactly who these two young men really are and protect them from the police.

With the exception of Gere, the cast of “Miles from Home” is largely populated with members of Chicago’s Steppenwolf Theatre.

Malkovich and Metcalf are familiar faces in the movies, but this is only the second starring role for Anderson (after “Orphans”) and he is strong in it, especially in his scenes with Miller in which he shares his growing fear that his brother is running wild, dangerously out of control.

The direction of the film is by another Steppenwolf member, Gary Sinise, who reflects the Steppenwolf tradition to go for broke, emotionally. There are scenes in the film – like the first falling-in-love scene – that a filmmaker with less courage would have shot in a more understated style. Steppenwolf has always been in love with melodrama, and “Miles from Home” is, too.